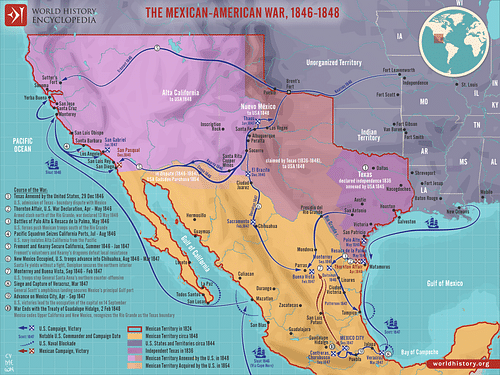

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) was a conflict between the United States and Mexico, sparked by the US annexation of Texas in 1845. Hoping to seize even more territory from Mexico, US President James K. Polk (served 1845-1849) used the Texas dispute to provoke a war, precipitating the US invasions of California, New Mexico, and the Mexican heartland. After the fall of Mexico City in September 1847, the Mexican government relinquished 529,000 square miles of territory to the US in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The war has often been regarded as an unjust invasion, both by contemporaries and later historians, and would only inflame the sectional divisions in the US that would lead to the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Background

In 1821, after over a decade of perpetual conflict, the Mexican War of Independence came to an end. For Mexico, the cost of winning independence from Spain came not only in blood but also in coin, as the once prosperous colony found its economy in tatters. Money barely circulated, the silver mines of Zacatecas and Guanajuato had been devastated, and throughout the country, ranches and farms stood deserted. To revitalize its economy and protect its vulnerable northern territories from Comanche and Apache raids, Mexico decided to invite Anglo-American settlers into Texas to exploit the region's untapped resources. Thousands of Anglo-Americans flooded into Texas – many of them bringing slaves – so that by 1830, the US transplants outnumbered the Hispanic Tejanos by more than two to one. Eventually, relations between these Anglo-American settlers and the Mexican government deteriorated, especially after Mexico abolished slavery. In October 1835, the settlers – who called themselves 'Texians' – rebelled, sparking the Texas Revolution (1835-36).

Initially, the Mexican army under Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794-1876) got the better of the rebels, scoring a victory at the Battle of the Alamo (23 February to 6 March 1836) and butchering 400 Texian prisoners at the Goliad Massacre (27 March). But the tide abruptly turned at the Battle of San Jacinto (21 April), when Texian forces under Gen. Sam Houston (1793-1863) surprised and defeated the Mexican army. Santa Anna was taken captive and forced to sign a treaty recognizing Texas' independence. But since the treaty was signed under duress – Santa Anna likely would have been executed had he not signed – it was not ratified by the Mexican Congress, which refused to recognize Texian independence. Thus, for the next several years, periodic fighting erupted across the Mexico-Texas border, as Texas began to operate like an independent republic. These events were closely watched by the United States. Since 1803, the US had claimed Texas, believing it to have been a rightful part of the Louisiana Purchase. Spain, however, had denied this claim and resisted every US attempt to buy the territory. Now, the US saw its opportunity, and, in 1843, President John Tyler (served 1841-1845) quietly opened talks to annex Texas.

While some Texians preferred to remain independent, others saw the benefit of joining the United States. The idea also gained momentum in the US where Southern Democrats, who wished to expand the institution of slavery, relished the idea of adding another 'slave state' to the Union, while other Americans believed Texas' annexation would be a huge step toward the 'Manifest Destiny' of their nation to spread its influence across the continent. After some hiccups, the US Congress passed a resolution offering annexation to Texas in February 1845 – Texas accepted and, in December, became the 28th state. This, of course, was seen as a hostile act by Mexico, who had yet to recognize Texas' independence, let alone its annexation to the US. Nor did Mexico agree with Texas' assertion that the Rio Grande constituted its southern boundary; historically, the border of Mexican Texas had ended at the Nueces River, 150 miles (240 km) north of the line Texas now claimed. But the newly elected US president, James K. Polk (1795-1849), did not care what Mexico thought – "I regard the question of annexation as belonging exclusively to the United States and Texas," he proclaimed in his inaugural address (quoted in Howe, 733).

A Democrat in the mold of Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), Polk had run on a platform of expansionism. Promising to guide the US to its 'Manifest Destiny' on the coasts of the Pacific, he was interested not only in acquiring Texas but also New Mexico and California. In November 1845, he dispatched a secret representative, John Slidell, to Mexico City with an offer to buy the Rio Grande border, New Mexico, and Alta California, all for $25 million. Once Slidell's purpose became known, however, his very presence in Mexico City was perceived as an insult. Negotiations were further hampered by the instability of the Mexican government; in 1846 alone, the Mexican presidency exchanged hands four times. Frustrated that he was getting nowhere with the negotiations, Slidell reported back to Washington that "a war will probably be the best mode of settling our affairs with Mexico" (quoted in Howe, 737). But Polk was way ahead of him – having anticipated that the negotiations would fail, he had spent the last few months positioning his armies to provoke a war with Mexico and seize the lands he desired by force.

Early Skirmishes

On 15 June 1845, before he sent Slidell to negotiate, Polk ordered Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor (1784-1850) into Texas with orders to "approach as near…the Rio Grande as prudence will dictate" (quoted in Howe, 734). Taylor – a career soldier known as 'Old Rough and Ready' – led the 4,000-man Army of Occupation to Corpus Christi at the mouth of the Nueces River, where he spent the next several months training his troops. In January 1846, when it became clear that Slidell's negotiations were going nowhere, Polk ordered Taylor to enforce the United States' claim to the disputed area by advancing to the banks of the Rio Grande. Taylor arrived in April and constructed the makeshift Fort Texas. Across the river lay the town of Matamoros, garrisoned by Mexican soldiers. When the Mexican commander demanded the American army withdraw, Taylor responded by blockading the mouth of the Rio Grande. Meanwhile, squadrons of US warships inched toward Mexico's chief ports, ready to blockade at a moment's notice. This was not something that Mexican President Mariano Paredes could ignore. On 23 April, he issued a proclamation blaming the US for hostilities and ordered the commander of Matamoros, Gen. Mariano Arista, to undertake defensive operations.

On the evening of 24 April 1846, US Capt. Seth Thornton led 68 dragoons out on a reconnaissance mission along the Rio Grande. The next morning, they were attacked by 2,000 Mexican cavalrymen; in what became known as the Thornton Affair, 11 American soldiers were killed, and the rest were captured. On 1 May, Taylor pulled his army out of Fort Texas to protect his supply lines, leaving behind only a small garrison. Two days later, the Mexican artillery at Matamoros began to bombard the fort. After consolidating his forces, Taylor returned to relieve the fort but was intercepted by Arista's army at the Battle of Palo Alto (8 May). With the help of their 'flying artillery', the Americans held their ground, forcing Arista to disengage and withdraw south. Taylor pursued and attacked Arista's retreating forces at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma (9 May), which devolved into bloody hand-to-hand fighting. The Mexican army was forced back across the Rio Grande, allowing Taylor to relieve Fort Texas, which he renamed Fort Brown after its fallen commander. In Washington, D.C., word of the Thornton Affair led Congress to issue a declaration of war on 13 May 1846 – support for the war was incredibly partisan, with Democrats generally in favor and Whigs generally opposed.

Conquest of California & New Mexico

Polk's plan, of course, required the rapid seizure of both New Mexico and Alta California. As early as June 1845, US Commodore John D. Sloat of the Pacific Squadron was ordered to occupy San Francisco as soon as he learned that war had broken out. Likewise, Capt. John C. Frémont (1813-1890) led a military expedition overland to the Oregon Territory, so that he could be ready to strike when the time came. Frémont's arrival in May 1846 emboldened the small number of American pioneers who had settled in Alta California to rebel against Mexican authorities. On 14 June, 30 American settlers seized the town of Sonoma and raised their flag, depicting a crudely drawn bear. Frémont immediately moved in to support the rebels and helped them beat back the Mexican militia. They declared independence, establishing the short-lived California Republic. When Sloat arrived in San Francisco on 9 July, he proclaimed the permanent annexation of California to the United States. The Bear Flag that had flown over Sonoma was lowered, replaced with the Stars and Stripes.

Meanwhile, US Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny marched from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, at the head of the 1,700-man Army of the West. Tasked with the capture of New Mexico, Kearny entered Santa Fe unopposed on 15 August – the Mexican governor, Manuel Armijo, had disbanded his militia and fled to Chihuahua, perhaps after accepting a bribe. Kearny stayed long enough to set up a provisional government before pressing on to aid in the conquest of Alta California. On 17 January 1847, Pueblos and Mexicans joined together and rebelled against the US occupation of New Mexico in the Taos Revolt. The insurrectionists killed many of the occupying Americans, including the provisional governor Charles Bent, whose scalp was paraded through the streets. The revolt was ultimately put down, and 16 insurrectionists were hanged as traitors, despite the secretary of war's ruling that they had never sworn allegiance to the US and could not be guilty of treason. Kearny's main army, meanwhile, arrived in Alta California in November 1846, where the local Californios had also revolted against US occupation. Kearny joined forces with US Commodore Robert F. Stockton to defeat the Californios at the Battle of Río San Gabriel (8 January 1847). A few days later, a regional peace treaty was signed at Cahuenga, pacifying Alta California. Thus, by early 1847, both New Mexico and California were under US control.

Monterrey & Buena Vista

After his initial victories around Fort Brown, Gen. Taylor led his army across the Rio Grande. He seized first Matamoros and then Camargo, where his army spent an agonizing six weeks baking in the scorching summer sun. Taylor's army was comprised mainly of untrained volunteers, who did not possess the life-saving sanitation habits of the regular soldiers. Consequently, diseases like dysentery were rampant, carrying off one in eight men – as Lt. George B. McClellan observed, "the volunteers literally die like dogs" (quoted in Howe, 771). Desertion, too, was endemic, with hundreds of troops fleeing or even defecting; enough Irish-American immigrants went over to the Mexican army to form their own battalion, the celebrated San Patricios.

After his long stay at Camargo, Taylor marched his 6,000 able-bodied troops to the strategic city of Monterrey, defended by 7,000 Mexican soldiers and 3,000 irregular troops. The resultant Battle of Monterrey (21-24 Sept. 1846) was long and hard-fought, devolving into bloody urban combat as US and Mexican troops struggled over every street. On the fourth day of fighting, the two sides agreed to an armistice where Taylor would allow the Mexican army to evacuate Monterrey in exchange for the city's surrender. While this was certainly prudent, President Polk was outraged when he learned of the armistice, believing that Taylor had missed his chance to destroy the Mexican army. Polk decided to strip Taylor's army of its veteran troops, sending them to another army preparing for an assault on Veracruz.

This was not the first time Polk had meddled in the war. His administration had been in contact with Santa Anna, who had been living in disgrace and political exile in Cuba. After the former Mexican leader assured the Americans that he would make peace, Polk helped Santa Anna return to Mexico, where he swiftly regained the presidency. But Santa Anna had played Polk for a fool; no sooner had he seized power in Mexico City than he put together an army of 20,000 men and rushed to attack Taylor's weakened army. The ensuing Battle of Buena Vista (22-23 Feb 1847) was the largest battle of the war. Though the Americans were outnumbered, they commanded excellent defensive ground and were able to withstand wave after wave of Mexican assault. In the end, both armies claimed victory – the Americans because they retained control of the battlefield, the Mexicans because they took several flags, cannons, and prisoners of war. Although he initially wanted to renew the fight, Santa Anna was persuaded by his officers to retreat to San Luis Potosi, which he did on the frosty evening of 23 February. In the wake of his retreating army, hundreds of wounded Mexican soldiers were abandoned to die.

Scott's Invasion

On 9 March 1847, only two weeks after Buena Vista, a second front was opened when a convoy of over a hundred American ships dropped off 10,000 soldiers three miles south of the port city of Veracruz. This army was commanded by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott (1786-1866), a hero of the War of 1812 and the US Army's senior general. He wasted no time launching an artillery bombardment of Veracruz; outmatched by the superior American artillery, the city fell on 26 March. Scott did not linger but began his march toward Mexico City, following the same route that Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors took three centuries before. Santa Anna marshaled another army to oppose him, and the opposing forces clashed at the Battle of Cerro Gordo (18 April 1847). Once again aided by their artillery, the Americans outmaneuvered the Mexican army, which broke and fled.

Continuing his advance, Scott took the city of Puebla, where he waited six weeks for reinforcements. Since Mexican guerrilla fighters were harassing his supply lines, he made the decision to cut himself off from his base of operations and live off the land. He marched through the mountain passes on 7 August and defeated another large Mexican army at the Battle of Contreras (19-20 August 1847). To cover their retreat after the battle, the Mexicans left some soldiers in the monastery of San Mateo, protecting the bridge over the Rio Churubusco. Scott ordered the monastery taken, leading to the bloody Battle of Churubusco (20 Aug). Wave after wave of American assault was repulsed, and the monastery's defenders surrendered only after running out of ammunition. Among the defenders were the San Patricios, who had made their last stand knowing the fate that awaited them should they be captured – indeed, 50 of the Irish defectors were executed after falling back into American hands.

At this point, Scott could have entered Mexico City but chose not to, believing that his starving troops would pillage and burn. Instead, he opened negotiations for a truce. The talks broke down, however, and hostilities resumed on 6 September. Santa Anna, hoping to rouse the populace in defense of the capital, urged his people to "preserve your altars from infamous violation, and your daughters and your wives from the extremity of insult" (quoted in Howe, 787). On 8 September, the Americans raided a flour mill called Molina del Rey, after receiving faulty reports that the Mexicans were casting cannonballs there; the Battle of Molina del Rey turned into a major battle and cost the Americans 800 casualties. On 13 September, the Americans won the Battle of Chapultepec, seizing a vital Mexican stronghold. After these bloody battles reduced the Mexican defenses, Scott's troops entered Mexico City on 14 September 1847. Santa Anna resigned the presidency on 16 September, and the Mexican government set up a provisional capital at Queretaro. The war was all but over – while guerrilla fighters continued harassing US forces, the Mexican army no longer possessed the capacity to fight. The question was whether peace could be negotiated before the Mexican government collapsed and the country devolved into anarchy.

End of War

Scott's successful invasion, as well as the swift conquests of New Mexico and Alta California, left Polk with a sense of total victory. Hungry for more land, he began making plans to acquire additional Mexican territory, such as Baja California, with some Democrats even calling for the annexation of all Mexico. But a wrench was thrown into Polk's imperialist plans by Nicholas Trist (1800-1874), the American negotiator embedded within Scott's army. Trist wanted to make a treaty that could realistically end the war, and he knew that the Mexican Congress would never accept Polk's new demands. Additionally, Trist was ashamed by his country's conduct in the war and refused to ask for more land than he had to. In November 1847, Trist was recalled by the Polk administration; however, he ignored these orders, fearing that the window to negotiate was quickly closing.

On 2 February 1848, Trist and the Mexican commissioners signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ceded Alta California, New Mexico, and Texas to the US in exchange for $15 million. The US Congress, eager to end the war, ratified the treaty. Though the imperialist Polk was disappointed, he had gotten everything he initially hoped for, and he left office having expanded the territory of the US more than any other president. But for the US, the true price of this 'wicked war' – as Ulysses S. Grant would call it – was yet to be fully realized. Debate over whether slavery should expand into the so-called 'Mexican Cession' would inflame the sectional crisis between North and South that would lead to the American Civil War.