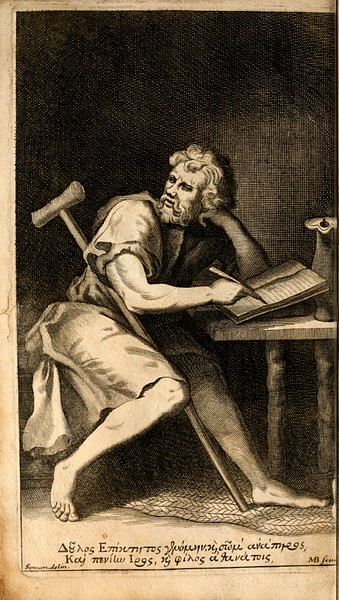

Epictetus (l.c. 50 - c. 130 CE) was a Stoic philosopher best known for his works The Enchiridion (the handbook) and his Discourses, both foundational works in Stoic philosophy and both thought to have been written down from his teachings by his student Arrian.

Stoicism is the belief that the individual is wholly responsible for his or her interpretations of circumstance and that all of life is natural and normal in spite of one's impressions. To the Stoics, philosophy was synonymous with life. One did not dabble in philosophy, one became fully immersed in it to understand and appreciate how best to live one's life.

The foundations of Stoicism, especially its recognition of the logos, an underlying force behind all things, was first laid by the Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus (l. c. 500 BCE). Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, then developed the philosophy c. 390 BCE and expounded upon it through his Cynic School (though, no doubt, mixed with Socratic concepts). These ideas were then further developed by the later philosopher Zeno of Citium in c. 300 BCE.

The Greek Stoics (the so-called `Old Stoa') Cleanthes and Chryissippus, who followed Zeno of Citium, wrote many volumes on the Stoic way of life but, unfortunately, of the 165 works attributed to Chrysippus, we have only fragments and the same holds true for Cleanthes. Their influence must have been far-reaching, however, because Stoic principles were known and practiced as far away as Rome.

Early Life

Epictetus was born in the Phrygian city of Hierapolis in Asia Minor to a slave woman and so was, himself, a slave. He was granted his freedom sometime after the death of Emperor Nero in the year 68 CE by his master Epaphroditus who had also been a slave and was freed by Nero for revealing a coup against the Emperor. Tacitus calls Epaphroditus “Nero's Freedman” and reports he was with Nero when the Emperor committed suicide, and offered to help him do so.

It should not seem strange that Epaphroditus, having been a slave, should own slaves once he, himself, had been freed. According to Nardo, “Slavery was the largest and most entrenched social institution in ancient Rome (especially at its height, between 200 BCE and 200 CE) and affected every aspect of life and society”(41). Epaphroditus, as secretary to emperor Nero, would have been expected to own slaves as standard custom.

Epaphroditus, recognizing his slave's intellectual abilities, recommended the young Epictetus to study with the great Stoic teacher C. Musonius Rufus and, clearly, Rufus influenced the younger man greatly as Epictetus' thought seems almost identical to some of the fragments we have of Musonius Rufus. Rufus was very impressed by Epictetus' keen mind and trained him well in the discipline of Stoic philosophy.

Once freed, Epictetus set up his own school and taught the philosophy to others until he, along with all the other philosophers in Rome, was banished by the emperor Domitian in the year 89 CE. Even so, the impact of Epictetus' thought became an integral part of Roman understanding. Scholar Forrest E. Baird writes:

Despite Emperor Domitian's condemnation, Stoicism had a special appeal to the Roman mind. The Romans were not much interested in the speculative and theoretical content of Zeno's early Stoa. Instead, in the austere moral emphasis of Epictetus, with his concomitant stress on self-control and superiority to pain, the Romans found an ideal for the wise man, whereas the Stoic description of natural law provided a basis for Roman law. One might say that the pillars of republican Rome tended to be Stoical, even if some Romans had never heard of Stoicism. (519)

Epictetus' influence was not confined to Rome, however, as his banishment led to his formation of the school which would preserve his teachings.

Nicopolis

Epictetus traveled to Nicopolis, Greece where he opened a Stoic school and taught philosophy through lectures, and by his own example in living, up until his death in the year 130 CE. Among his students was the young historian Flavius Arrianus (popularly known as Arrian) whose classnotes (written in Koine Greek although Epictetus taught in Attic Greek) have preserved Epictetus' thought as the philosopher himself apparently wrote nothing down.

Arrian collected and edited the lectures and discussions he attended in eight books, of which four remain extant, and distilled his master's thoughts in the Enchiridion. That philosophy was a way of living, not merely an academic discipline, is apparent throughout the Enchiridion and is expanded upon in Epictetus' other work, the Discourses, which Arrian purports to be verbatim transcripts of discussions he had and classes he and others participated in with Epictetus (though this is doubtful). Scholars are confident that the works ascribed to Epictetus are his own, not the creation of Arrian, based upon Arrian's other extant writings.

Logos

Epictetus' focus was on the responsibility of the individual to live the best life possible. He insisted that human beings do have freedom of choice in all matters even though that choice may be limited by the operation of the logos. This logos (Greek for `word' or `speech' but containing a much greater range of meaning including `to convey thought') was an eternal force which moved through all things and all people, which created and guided the operation of the universe and which had always existed. In many English translations of Epictetus' works logos is often given as God. As Hays writes:

Logos operates both in individuals and in the universe as a whole. In individuals it is the faculty of reason. On a cosmic level it is the rational principle that governs the organization of the universe. In this sense it is synonymous with 'nature', 'Providence' or 'God' (when the author of John's Gospel tells us that `the Word' – logos –was with God and is to be identified with God, he is borrowing Stoic terminology). (xix)

This use of logos as a force characterized by rationality, and perceived through reason, though it has roots in the teachings of Heraclitus, was more clearly explained by Epictetus as Heraclitus' writings were thought to be difficult to understand. According to Epictetus, the logos is the underlying form of the perceived world which sets the parameters of the human experience and maintains the order of the universe by immutable laws.

Because of the natural operation of this logos, then, the individual was limited in choice but still had the power over how to interpret external circumstance and how to respond to it. As the Enchiridion puts it, “Men are disturbed not by the things which happen, but by the opinions about the things: for example, death is nothing terrible, for if it were it would have seemed so to Socrates; for the opinion about death, that it is terrible, is the terrible thing.” How one chooses to interpret external circumstances, not the circumstances themselves, leads one to enjoy a good life or suffer from a bad one. The immense power, and responsibility, of personal choice and free will was at the heart of the Stoicism of Epictetus while he simultaneously acknowledged that there was much in life which was simply beyond one's control. As Hays has it:

The Stoics [defined] free will as a voluntary accommodation to what is in any case inevitable. According to this theory, man is like a dog tied to a moving wagon. If the dog refuses to run along with the wagon he will be dragged by it, yet the choice remains his: to run or be dragged. In the same way, humans are responsible for their choices and actions, even though these have been anticipated by the logos and form part of its plan. (xix-xx)

Human choice may be bound by the laws of the logos but that does not mean people's choices are directed by any outside force. It is always one's individual choice to engage in life willingly or to be dragged through existence reluctantly.

Epictetus insisted that, though life may be subject to constant change, human beings are ultimately responsible for how they interpret and respond to those changes. By accepting responsibility for the way one views the world, and how that view affects one's behavior, one frees the self from slavery to external circumstances to become master of one's own life. It was this emphasis on the superiority of the individual over circumstance which made Stoicism so appealing to the Roman character.

Epictetus' work was so influential that it became the central doctrine of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE), known as `the last of the good emperors of Rome', who acknowledges Epictetus in his book, The Meditations. Aurelius was by no means the last person to draw strength and inspiration from the teachings of Epictetus as he is acknowledged by many as a formidable influence up to the present day.