L. Mestrius Plutarchus, better known simply as Plutarch, was a Greek writer and philosopher who lived between c. 45-50 CE and c. 120-125 CE. A prodigious and hugely influential writer, he is now most famous for his biographical works in his Parallel Lives which present an entertaining history of some of the most significant figures from antiquity.

Biography

Plutarch was born to an ancient aristocratic Theban family in Chaeronea in central Greece sometime before 50 CE. His father was called Autobulus and his grandfather Lamprias, both of whom are mentioned in his work. Although Plutarch visited Athens often, studying there philosophy under Ammonius, and he travelled to both Alexandria in Egypt and Italy, he lived the first part of his life in Chaeronea where he participated in public life and held several magistracy positions. He married a woman named Timoxena with whom he had at least five children. From middle age, Plutarch was a priest at the sacred site of Delphi with its famous oracle of Apollo. He is credited with aiding the revival of interest in such ancient cults during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. Indeed, Plutarch supervised the new building projects of both emperors at Delphi.

Plutarch mixed in influential circles and his friends included the consuls C. Minicius Fundanus, L. Mestrius Florus (who granted Plutarch his Roman citizenship), and Q. Sosius Senecio. Parallel Lives was dedicated to the latter. Further evidence of Plutarch's proximity to the higher echelons of the Roman elite are Trajan's granting him the rare honorary title of ornamenta consularia and Hadrian appointing him imperial procurator in Achaea. Plutarch passed on his experience of high politics in his Rules for Politicians, a treatise giving advice for young aspiring public servants. Besides these practical positions Plutarch was also a philosopher. He adhered to Platonist principles and he himself taught philosophy in his own school in Chaeronea.

Plutarch's Works

Plutarch was a prolific writer who became ever more productive the older he became but, unfortunately, a large number of his works have been lost. Just what is missing is indicated in a 4th-century list known as the Catalogue of Lamprias. Here there are mentioned 227 works which include biographies and an eclectic array of writings collectively referred to as Moralia. These latter include rhetorical works, moral philosophy, religious descriptions, and discussions of such matters as prophecy and the afterlife. There was also a discussion of Plato's Timaeus, and critiques of the Stoic and Epicurean schools of philosophy. History was not neglected either as Plutarch wrote several works on ancient religious practices in both the Greek and Roman worlds as well as descriptions on such varied topics as education and music. Added to all this are many seemingly random discussions and treatises such as Advice on Marriage and How to Tell a Friend from a Flatterer. The Catalogue of Lamprias, though, is not complete as some of the writer's 128 surviving works are not on it.

Included in the surviving manuscripts are 50 Lives. Of Plutarch's biographies of the Caesars (Augustus to Vitellius), alas, only Galba and Otho survive. Other notable absentees which we know Plutarch described are biographies of the Greek lyric poet Pindar and the great Theban general Epaminondas. Nevertheless, those biographies which remain are ample material to establish Plutarch as one of the great writers of antiquity and a vital historical source on some of the most significant figures in history.

Plutarch wrote in a rich metaphorical style, and his work often has a personal and affectionate quality aided by his frequent mention of family members and close friends. Indeed, Plutarch is often a speaker in his works, especially those in dialogue form which contain extended speeches and personal characterisation.

Parallel Lives

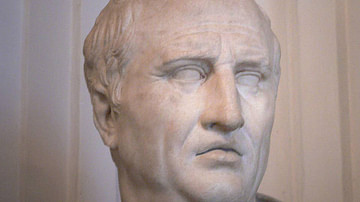

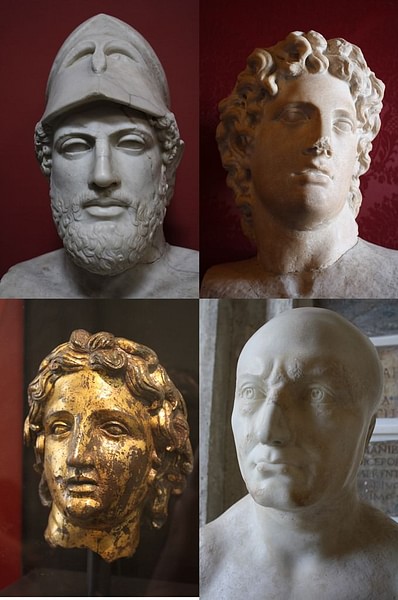

Plutarch's approach to biographies was to take two historical figures - one Greek and one Roman - and present them in parallel comparison, hence their frequent collective title Parallel Lives. The two colourful biographies were then followed by a more austere concluding synkrisis or comparison. 23 pairs survive, 19 with their synkrisis. Examples of the pairings are Alexander and Julius Caesar, Epaminondas and Scipio Africanus (now lost), and Demosthenes and Cicero. As with most ancient writers, Plutarch was not so interested in a detailed chronological account of the subject's life but, rather, he sought to pick out their essential good and bad qualities and present a portrait from a moral perspective. As translator Ian Scott-Kilvert eloquently puts it,

Plutarch has an unerring sense of the drama of men in great situations. His eye ranges over a wider field of human action than any of the classical historians. He surveys men's conduct in war, in council, in love, in the use of money...in religion, in the family, and he judges as a man of wide tolerance and ripe experience. (11)

The biographies are, then, after an initial examination of the formative years and education of the subject, a series of entertaining anecdotes and incidents which Plutarch believed illustrated the person's character, their virtues and their vices. This approach has, of course, frustrated later historians as Plutarch's information could be variously based on fact, personal experience, hearsay, or just plain old gossip.

Legacy

There has never really been a time when Plutarch was not read. His works, especially those on philosophy and education, continued to be highly regarded and popular in Late Antiquity by scholars and early Christians, in the Byzantine period, and the Renaissance. Plutarch's accounts of historical figures have also been used as source material by a wide range of later writers including Shakespeare, Rousseau, and Montaigne. We have seen that Plutarch's eclectic approach to history has lessened his esteem in the eyes of modern historians but he has made a comeback in recent years and is now acknowledged as a valuable source who gives a unique insight into how the classical world was viewed from the inside.

Below is a selection of extracts from Plutarch's work.

On Themistocles:

He was also greatly admired for the example he made of the interpreter, who arrived with the envoys from the Persian king to demand earth and water in token of submission. He had this interpreter arrested and put to death by a special decree of the people, because he had dared to make use of the Greek language to transmit the commands of a barbarian. (The Rise & Fall of Athens, 83)

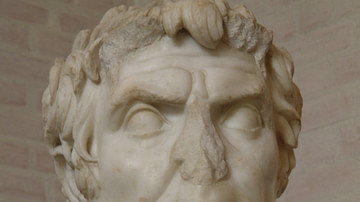

On Pericles:

His physical features were almost perfect, the only exception being his head, which was rather long and out of proportion. For this reason almost all his portraits show him wearing a helmet, since the artists apparently did not wish to taunt him with this deformity. (The Rise & Fall of Athens, 167)

On Alcibiades:

The fact was that his voluntary donations, the public shows he supported, his unrivalled munificence to the state, the fame of his ancestry, the power of his oratory and his physical strength and beauty, together with his experience and prowess in war, all combined to make the Athenians forgive him everything else, and they were constantly finding euphemisms for his lapses. (The Rise & Fall of Athens, 259)

Alexander went in person to see him [Diogenes] and found him basking at full length in the sun. When he saw so many people approaching him, Diogenes raised himself a little on his elbow and fixed his gaze upon Alexander. The king greeted him and inquired whether he could do anything for him. 'Yes', replied the philosopher, 'you can stand a little to one side out of my sun.' Alexander is said to have been greatly impressed by this answer and full of admiration for the hauteur and independence of mind of a man who could look down on him with such condescension. So much so that he remarked to his followers, who were laughing and mocking the philosopher as they went away, 'You may say what you like, but if I were not Alexander, I would be Diogenes.' (The Age of Alexander, 266)

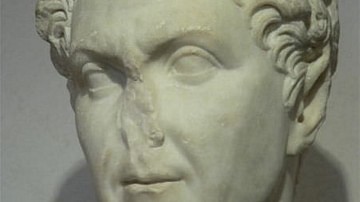

On Pyrrhus:

The general opinion of him was that for warlike experience, daring and personal valour, he had no equal among the kings of his time; but what he won through the feats of his arms he lost by indulging in vain hopes, and through his obsessive desire to seize what lay beyond his grasp, he constantly failed to secure what lay within it. For this reason Antigonus compared him to a player at dice, who makes many good throws, but does not understand how to exploit them when they are made.' (The Age of Alexander, 414-415)