Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE) was the sixth king of the Amorite First Dynasty of Babylon best known for his famous law code which served as the model for others, including the Mosaic Law of the Bible. He was the first ruler able to successfully govern all of Mesopotamia, without revolt, following his initial conquest.

He is also known as Ammurapi and Khammurabi and assumed the throne from his father, Sin-Muballit, who had stabilized the kingdom but could not expand upon it. The kingdom of Babylon comprised only the cities of Babylon, Kish, Sippar, and Borsippa when Hammurabi came to the throne but, through a succession of military campaigns, careful alliances made and broken when necessary, and political maneuvers, he held the entire region under Babylonian control by 1750 BCE.

According to his own inscriptions, letters and administrative documents from his reign, he sought to improve the lives of those who lived under his rule. As noted, he is best known in the modern day for his law code which is often cited as being the first in history although it is not. There were earlier codes in Mesopotamia but Hammurabi's were the clearest and most inclusive and so came to serve as a model for other cultures, including the laws set down by Hebrew scribes in the Bible.

Background & Rise to Power

The Amorites were a nomadic people who migrated across Mesopotamia from the coastal region of Eber Nari (modern day Syria) at some point prior to the 3rd millennium BCE and by 1984 BCE were ruling in Babylon. The fifth king of the dynasty, Sin-Muballit (r. 1812-1793 BCE), successfully completed many public works projects but was unable to expand the kingdom or compete with the rival city of Larsa to the south.

Larsa was the most lucrative trade center on the Persian Gulf and the profits from this trade enriched the city and encouraged expansion so that most of the cities of the south were under Larsa's control. Sin-Muballit led a force against Larsa but was defeated by their king Rim Sin I. At this point it is uncertain what exactly happened, but it seems that Sin-Muballit was compelled to abdicate in favor of his son Hammurabi. Whether Rim Sin I thought Hammurabi would be less of a threat to Larsa is also unknown but, if so, he would be proven wrong. The historian Durant writes:

At the outset of [Babylonian history] stands the powerful figure of Hammurabi, conqueror and lawgiver through a reign of forty-three years. Primeval seals and inscriptions transmit him to us partially – a youth full of fire and genius, a very whirlwind in battle, who crushes all rebels, cuts his enemies into pieces, marches over inaccessible mountains, and never loses an engagement. Under him the petty warring states of the lower valley were forced into unity and peace, and disciplined into order and security by an historic code of laws. (219)

Initially, Hammurabi gave Rim Sin I no cause for alarm. He began his reign by centralizing and streamlining his administration, continuing his father's building programs and enlarging and heightening the walls of the city. He instituted his famous code of laws (c. 1772 BCE), paid careful attention to the needs of the people, improved irrigation of fields and maintenance of the infrastructures of the cities under his control, while also building opulent temples to the gods. At the same time he was setting his troops in order and planning his campaign for the southern region of Mesopotamia.

Conqueror of Mesopotamia

The scholar Stephen Bertman notes how Hammurabi's personal character worked to his advantage early in his reign:

Hammurabi was an able administrator, an adroit diplomat, and canny imperialist, patient in the achievement of his goals. Upon taking the throne, he issued a proclamation forgiving people's debts and during the first five years of his reign further enhanced his popularity by piously renovating the sanctuaries of the gods, especially Marduk, Babylon's patron. Then, with his power at home secure and his military forces primed, he began a five-year series of campaigns against rival states to the south and east, expanding his territory. (87)

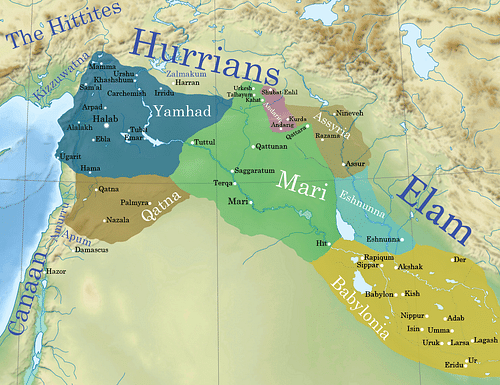

When the Elamites invaded the central plains of Mesopotamia from the east, Hammurabi allied himself with Larsa to defeat them. That accomplished, he broke the alliance and swiftly took the cities of Uruk and Isin, previously held by Larsa, by forming alliances with other city-states such as Nippur and Lagash. The alliances he made with other states would repeatedly be broken when the king found it necessary to do so but, as rulers continued to enter into pacts with Hammurabi, it does not seem to have occurred to any of them that he would do the same to them as he had previously to others.

Once Uruk and Isin were conquered, he turned and took Nippur and Lagash and then conquered Larsa. A technique he seems to have used first in this engagement would become his preferred method in others when circumstances allowed: the damming up of water sources to the city to withhold them from the enemy until surrender or, possibly, withholding the waters through a dam and then releasing them to flood the city before then mounting an attack. This was a method previously used by Hammurabi's father but with considerably less efficacy. Larsa was the last stronghold of Rim Sin and, with its fall, there was no other force to stand against the king of Babylon in the south.

With the southern part of Mesopotamia under control, Hammurabi turned north and west. The Amorite Kingdom of Mari in Syria had long been an ally of Amorite Babylon, and Hammurabi continued friendly relations with the king Zimri-Lim (r. 1775-1761 BCE). Zimri-Lim had led successful military campaigns through the north of Mesopotamia and, owing to the wealth generated from these victories, Mari had grown to be the envy of other cities with one of the largest and most opulent palaces in the region.

Scholars have long debated why Hammurabi would break his alliance with Zimri-Lim but the reason seems fairly clear: Mari was an important, luxurious, and prosperous trade center on the Euphrates River and possessed great riches and, of course, water rights. Holding the city directly, instead of having to negotiate for resources, would be preferable to any ruler and certainly was so to Hammurabi. He struck swiftly at Mari in 1761 BCE and, for some reason, destroyed it instead of simply conquering it.

This is a much greater mystery than why he would march against it in the first place. Other conquered cities were absorbed into the kingdom and then repaired and improved upon. Why Mari was such an exception to Hammurabi's rule is still debated by scholars, but the reason could be as simple as that Hammurabi wanted Babylon to be the greatest of the Mesopotamian cities and Mari was a definite rival for this honor.

Zimri-Lim is thought to have been killed in this engagement as he vanishes from the historical record in that same year. From Mari, Hammurabi marched on Ashur and took the region of Assyria and finally Eshnunna (also conquered by damming up of the waters) so that, by 1755 BCE, he ruled all of Mesopotamia.

Hammurabi's Code & the Care of the People

Although Hammurabi spent a considerable amount of time on campaign, he made sure to provide for the people whose lands he ruled over. A popular title applied to Hammurabi in his lifetime was bani matim, 'builder of the land', because of the many building projects and canals he ordered constructed throughout the region.

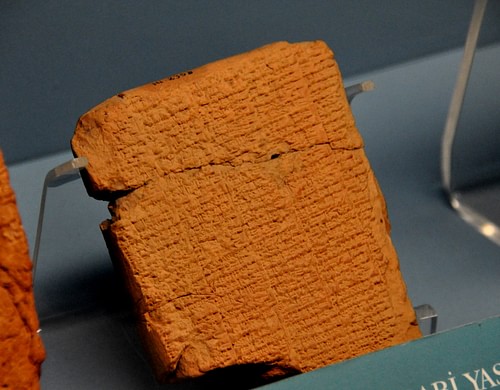

Documents from the time attest to the efficacy of Hammurabi's rule and his sincere desire to improve the lives of the people of Mesopotamia. These letters and administrative works (such as directives for the building of canals, food distribution, beautification and building projects, and legal issues) support the view which Hammurabi held of himself. The prologue to his famous law code begins:

When the lofty Anu, King of the Annunaki and Bel, Lord of Heaven and Earth, he who determines the destiny of the land, committed the rule of all mankind to Marduk, when they pronounced the lofty name of Babylon, when they made it famous among the quarters of the world and in its midst established an everlasting kingdom whose foundations were firm as heaven and earth – at that time Anu and Bel called me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, the worshipper of the gods, to cause justice to prevail in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil, to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak, to enlighten the land and to further the welfare of the people. Hammurabi, the governor named by Bel, am I, who brought about plenty and abundance. (Durant, 219)

His law code is not the first such code in history (though it is often called so) but is certainly the most famous from antiquity prior to the code set down in the biblical books. The Code of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100-2050 BCE), which originated with either Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) or his son Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), is the oldest code of laws in the world. Hammurabi's code differed from the earlier laws in significant ways. The historian Kriwaczek explains this, writing:

Hammurabi's laws reflect the shock of an unprecedented social environment: the multi-ethnic, multi-tribal Babylonian world. In earlier Sumerian-Akkadian times, all communities had felt themselves to be joint members of the same family, all equally servants under the eyes of the gods. In such circumstances disputes could be settled by recourse to a collectively accepted value system, where blood was thicker than water, and fair restitution more desirable than revenge. Now, however, when urban citizens commonly rubbed shoulders with nomads following a completely different way of life, when speakers of several west Semitic Amurru languages, as well as others, were thrown together with uncomprehending Akkadians, confrontation must all too easily have spilled over into conflict. Vendettas and blood feuds must often have threatened the cohesion of the empire. (180)

The Code of Ur-Nammu certainly relies on the concept of “joint members of the same family” in that an underlying understanding by the people of proper behavior in society is assumed throughout. Everyone under the law was expected to already know what the gods required of them, and the king was expected simply to administer the god's will. Historian Karen Rhea Nemet-Najat writes:

The king was directly responsible for administering justice on behalf of the gods, who had established law and order in the universe. (221)

Hammurabi's code was written in a later time when one tribe's or city's understanding of the will of the gods might be different from another's. In order to simplify matters, Hammurabi's code sought to prevent vendetta and blood feuds by stating clearly the crime - and the punishment which would be administered

If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out.

If he break another man's bone, his bone shall be broken.

If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out.

If a builder build a house for someone, and does not construct it properly,

And the house which he built fall in and kill its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

If it kill the son of the owner of the house, the son of that builder shall be put to death.

Unlike the earlier Code of Ur-Nammu, which imposed fines or penalties of land, Hammurabi's code epitomized the principle known as Lex Talionis, the law of retributive justice, in which punishment corresponds directly to the crime, better known as the concept of 'an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth', made famous from the later law code of the Old Testament, exemplified in this passage from the Book of Exodus:

If people are fighting and hit a pregnant woman and she gives birth prematurely but there is no serious injury, the offender must be fined whatever the woman's husband demands and the court allows. But if there is serious injury, you are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise. (Exodus 21:22-25)

Hammurabi's law code thus set the standard for future codes in dealing strictly with the evidence of the crime and setting a specific punishment for that crime. What decided one's guilt or innocence, however, was the much older method of the Ordeal, in which an accused person was sentenced to perform a certain task (usually being thrown into a river or having to swim a certain distance across a river) and, if they succeeded, they were innocent and, if not, they were guilty. Hammurabi's code stipulates that:

If a man's wife has been pointed out because of another man, even though she has not been caught with him, for her husband's sake she must plunge into the divine river.

The woman who did so and survived the ordeal would be recognized as innocent, but then her accuser would be found guilty of false witness and punished by death. The ordeal was resorted to regularly in what were considered the most serious crimes, adultery and sorcery, because it was thought these two infractions were most likely to undermine social stability. Sorcery, to an ancient Mesopotamian, would not have exactly the same definition as it does in the modern day but would be along the lines of performing acts that went against the known will of the gods — acts which reflected on oneself the kind of power and prestige only the gods could lay claim to. Tales of evil sorcerers and sorceresses are found throughout many periods of Mesopotamian history and the writers of these tales always have them meet with a bad end as, it seems, they also did when submitted to the Ordeal.

Hammurabi's Death & Legacy

By 1755 BCE, when he was the undisputed master of Mesopotamia, Hammurabi was old and sick. In the last years of his life his son, Samsu-Iluna, had already taken over the responsibilities of the throne and assumed full reign in 1749 BCE. The conquest of Eshnunna had removed a barrier to the east that had buffered the region against incursions by people such as the Hittites and Kassites. Once that barrier was gone, and news of the great king weakening spread, the eastern tribes prepared their armies to invade. Hammurabi died in 1750 BCE, and Samsu-Iluna was left to hold his father's realm against the invading forces while also keeping the various regions of Babylonia under control of the city of Babylon; it was a formidable task of which he was not capable.

The vast kingdom Hammurabi had built during his lifetime began to fall apart within a year of his death, and those cities that had been part of vassal states secured their borders and announced their autonomy. None of Hammurabi's successors could put the kingdom back together again, and first the Hittites (in 1595 BCE), then the Kassites invaded.

The Hittites sacked Babylon and the Kassites inhabited and re-named it. The Elamites, who had been so completely defeated by Hammurabi decades before, invaded and carried off the stele of Hammurabi's Law Code which was discovered at the Elamite city of Susa in 1901 CE.

Hammurabi is best remembered today as a lawgiver whose code served as a standard for later laws but, in his time, he was known as the ruler who united Mesopotamia under a single governing body in the same way Sargon the Great of Akkad had done centuries before. He linked himself with great imperialists like Sargon by proclaiming himself “the mighty king, king of Babylon, king of the Four Regions of the World, king of Sumer and Akkad, into whose power the god Bel has given over land and people, in whose hand he has placed the reins of government” and, just like Sargon (and others), claimed his legitimate rule was ordained by the will of the gods.

Unlike Sargon the Great, however, whose multi-ethnic empire was continually torn by internecine strife, Hammurabi ruled over a kingdom whose people enjoyed relative peace following his conquest. The scholar Gwendolyn Leick writes:

Hammurabi remains one of the great kings of Mesopotamia, an outstanding diplomat and negotiator who was patient enough to wait for the right time and then ruthless enough to achieve his aims without stretching his resources too far. (83)

It is a testimony to his rule that, unlike Sargon or his grandson Naram-Sin from earlier times, Hammurabi did not have to re-conquer cities and regions repeatedly but, having brought them under Babylonian rule, was, for the most part, interested in improving them and the standard of living of the inhabitants (a notable exception being Mari, of course). His legacy as a lawgiver reflects his genuine concern for social justice and the betterment of the lives of his people.