This text is part of an article series on the Delian League.

The modern term Delian League refers to the primarily maritime συμμᾰχία or symmachy (offensive-defensive alliance) among various Greek poleis, which emerged after the second Mede invasion of the Hellenes (480-479 BCE), and dissolved when the Athenians surrendered to the Spartans at the end of the Peloponnesian War (404 BCE) – also called The Confederacy of Delos.

The alliance's name derives from the island of Delos, where the League originally housed its treasury. Member poleis would periodically meet in common synods to decide policy. The League possessed three explicit objectives: obtain both revenge against and reparations from the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, liberate all Hellenes from Mede domination, and guarantee the continued freedoms of Hellenic poleis.

The Delian League experienced exceptional achievements and expansion under Athenian leadership, but this also led ultimately to Athens' widespread interference, restrictions, and subordination of individual Greek poleis throughout the Aegean Sea and Greek mainland. Such actions would eventually drive the Delian League into a massive conflict against the other great symmachy of Ancient Greece, the Peloponnesian League of Sparta and its allies.

In many ways, scholars ultimately define the Delian League by the devastating Greek civil war it produced; the war that eventually destroyed it, the great “Peloponnesian War.” This war, however, did not unfold only against the Peloponnesians but would bring the entire alliance into motion and involve everyone in the Hellenes as well as the peoples of Sicily, Italy, Thrace, Phoenicia, Egypt, Macedon, and Persia.

The Delian League's almost unprecedented success ultimately led to its undoing.

ANCIENT GREEK CONFEDERACIES

Ancient Greeks had rather confined experiences with co-operative multi-polis confederations. Each polis inherently sought and adamantly protected both their ἐλευθερία (liberty or 'external freedom') and αὐτονομία (autonomy or 'internal freedom'). They also vigorously pursued and maintained αὐτάρκεια (independence or 'self-sufficiency'). Consequently, coalitions of multiple poleis often ran afoul of these civic corporate passions, which defined the nature of the self-contained polis itself.

Hellenic alliances varied according to the individual circumstances that created them. The ancient Greek term συμμᾰχία also emits the same inherent ambiguity as its English translation. The specific oaths exchanged determined above all other considerations the nature and extent of each individual alliance, and no two appear to have operated exactly the same in either scope or practice.

Ancient Greeks also crafted a narrower ἐπιμαχία or epimachy (defensive pact), where each polis would simply come to the aid of another in the case of some external threat. Broadly speaking, however, the wider symmachy would typically take one of two forms: an explicit hegemony or a broader 'mutually binding' agreement.

In a hegemony, the weaker, smaller, or poorer poleis swore oaths "to have the same friends and enemies" of a stronger ἡγεμών or hegemon (lit. leader). These poleis also pledged to follow the hegemon, "whithersoever that polis might lead." The hegemon, on the other hand, might or might not have had the reverse obligation. The Boeotian Confederation of Thebes and its neighbors and the Peloponnesian League of Sparta and its allies took this form (Thuc. 2.2.1, 4.91, 5.37.4-38.4; Hell. Oxy. 16.11).

In the mutual binding agreement, on the other hand, all poleis pledged fully reciprocal oaths, where each agreed to take counsel and provide support for one another equally. These alliances, however, did not in many cases carefully delineate between strictly offensive and defensive obligations for each member polis. The Anti-Persian Hellenic League assembled in 481 BCE took this form, though this league did not possess an official name (Hdt. 7.145.1, 148.1, 235.4).

In sum, those individual poleis that entered into a symmachy necessarily accepted a diminution of total, unrestricted liberty (ἐλευθερία) to realize certain benefits that official and specific cooperation with other poleis brought. In many ways, the Delian League superseded and ultimately replaced the Anti-Persian Hellenic League, although the latter never formally disbanded with the foundation of this new league.

CO-OPERATIVE LEAGUE OR ATHENIAN EMPIRE?

Scholars generally agree that Athens would come to use the appurtenances of the Delian League for self-serving ends. Many argue further that the Athenians engaged in oppressive imperialism from the earliest years, while still others hold the Delian League morphed into an 'Athenian Empire' by ca. 450 BCE, or even as early as 460 BCE, and certainly by the start of the Peloponnesian War (432 BCE). Not all students of Greek history, however, accept Athens created or led an actual empire in either the technical or truest senses.

Ancient Greek does not have words for 'empire' or 'imperialism,' which derived from the Latin imperium (power to command). Imperium denoted for the Romans the strongest and least restricted authority over citizens and foreigners. Ancient Greeks, however, did not separate the idea of power to rule in itself from the office that wielded it. Disagreements evolve, for example, from how one might apply the Roman concept of imperium to Athens' rule of the Delian League. Did it operate in any way analogous to the Persian or Roman Empires?

The ancient Greeks nonetheless came to hold that what began as an offensive-defensive synod of equal and independent Greek poleis created specifically to resist Persian encroachments into the Aegean, as well as take the offensive against the Persian Empire itself, soon evolved into a simple 'Athenian Hegemony' and eventually into an arbitrary 'Athenian Rule.'

Evidence shows that within 30 years of inception the League's resources had shifted from primarily stopping (or checking) the might of Persia to advancing Athenian desires at home and abroad. Pinpointing and/or charting the actual substance of concrete changes in how the Delian League operated, which pushed this co-operative coalition into some form of imperial instrument, however, remains a difficult task at best.

THE PERSIAN WARS

Pausanias, nephew of the Spartan King Leonidas, commanded the combined Hellenic forces at Plataea (479 BCE). He also led the Greeks against Cyprus and Byzantium (478 BCE). The Samians and Chians, however, drove Pausanias away after he suffered a mutiny for exceedingly arrogant behavior and possibly treasonous negotiations with the Persians. The Spartans subsequently recalled him.

The Chians, Samians, and Lesbians then argued for Ionian Athens to replace Dorian Sparta as leader of the combined Greeks. The Athenian Xanthippus had supported the Spartan King Leotychides at Mycale, and the Athenians Aristides, son of Lysimachus, and Cimon, son of Miltiades, had already become leading voices during councils. Sparta's king, moreover, had already returned to the Peloponnese by this time. The Spartans, who historically resisted protracted foreign obligations, thus offered no objection. Sparta showed little interest (or unwillingness) to assume responsibility for the Aegean or extend its influence east of the Peloponnese.

The Athenians accepted the responsibility through a combination of pride and fear. Their pride stemmed from Athens' prominent roles at both Salamis and Marathon, and their fear resulted from Athens' growing dependence on unfettered maritime trade (especially the import of grain into Attica). The Athenians understood from the outset that they simply had the most to lose in any war against Persia.

Details of the subsequent negotiations, which took place off the coast of Byzantium, remain frustratingly obscure, but the sources show these Greeks decided to form a new, separate coalition in lieu of maintaining or expanding the original Anti-Persian Hellenic League. Representatives from throughout the Aegean islands and coastland poleis began to gather by early summer 477 BCE.

FOUNDING OF THE DELIAN LEAGUE

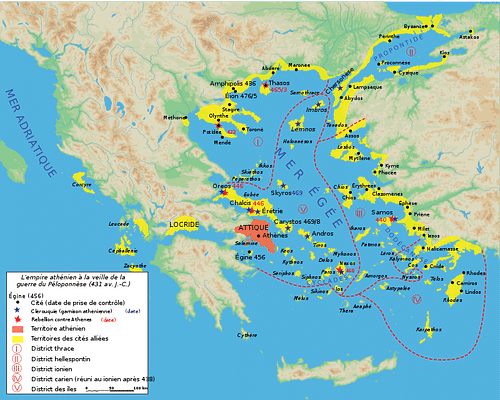

The Ancient Greeks headquartered their new alliance on the island of Delos, a historically sacred festival center for both the Ionian and Dorian Greeks. Approximately 36 Ionian poleis from Asia's west coast and the Propontis, 35 poleis from the Hellespont, and 57 poleis from Caria and Thrace (or the Chalcidice), as well as 20 or so poleis from the Aeolian Aegean islands comprised the nucleus of the Delian League – i.e., approximately 150 or so poleis initially formed the new alliance. No Peloponnesian poleis joined.

An Athenian would command the combined military forces. The Athenians also determined those poleis, which would provide ships and manpower and those, which would simply offer monetary contributions. The Athenians also appointed ten Athenian ἑλληνοταμίαι or Hellentamiai (Treasurers of the Hellenes) to oversee collections as well as the dispensing of funds from the temple as required. Presumably, League members would deliver the monies to the island by a designated date, but the exact procedures they used for collection unfortunately remain guess-work.

By mid-summer 477 BCE, the Athenian Aristides calculated the first φόρος or phoros (assessment). Aristides examined the land and revenue of each member polis and determined individual amounts "according to their ability to pay so that the grand total should be 460 [or 560] τάλαντα" or talenta or talents (Thuc. 1.96; Plut. Vit. Ar. 24.1; Diod. 11.47.1) (one talent = the value of 25.992 kg of pure silver). The process Aristides employed remains unknown, but scholars generally agree he first assessed all members of the League by financial obligation, then converted the amounts for the larger and wealthier poleis into equivalent naval contributions. The Athenian Tribute Lists, however, show the League collected (on balance) less than 400 talents annum until 454 BCE, a time when more tributaries existed. Scholars debate whether the naval commitments comprised the difference from the initial balances reported by Thucydides and Diodorus or if they should lower the reported first assessment (as textual corruptions) to match the Tribute Lists.

The League does not appear to have envisioned any contributions of heavy or light-armed land troops, but sources attest to their presence by 450 BCE. Athens, Chios, Samos, Lesbos, and other larger poleis provided the bulk of the League fleet, while the remaining poleis would deposit the required monies annually into the treasury on Delos. Subsequent assessments (i.e. adjustments to the annual tribute) would then take place in four year intervals.

Scholars speculate and debate the exact wording and nature of the initial oaths taken by the representatives of each member polis. Broadly speaking, however, each member agreed "to have the same enemies and friends" as well as "remain loyal and not desert" (Hdt. 9.106.4; Thuc. 1.44.1; Arist. Ath. Pol. 23.5; Plut. Vit. Arist. 25.1). Each representative sunk lumps of metal in the sea to symbolize the League's permanence (i.e. the alliance would endure until the iron swam).

STRUCTURE OF THE DELIAN LEAGUE

The arrangement and operation of the new alliance proved straightforward; the member poleis retained their independence, and the League would not interfere in their domestic affairs. The members would collectively determine the policy and actions of the League during meetings (synods) held on Delos. Each polis possessed one vote. How often or what time of the year the meetings on Delos convened remains unknown. Presumably an Athenian presided over these meetings, but exactly how Athens assumed a preeminent position in the League's congresses divides scholars.

In one view, Athens sat as a single voice in a unicameral congress of partners (ἰσόψηφος or isopsephos, equal vote, lit. equal pebble). In practice, however, numerous smaller poleis often sided with Athenian proposals. Athens thus emerged the dominating influence from the outset during the League's meetings by corralling other members and outvoting those poleis that disagreed with Athenian proposals (πολύψηφοι or polypsephoi, many votes, lit. many pebbles). This simple interpretation, however, presents some difficulties. Athenians commanded League campaigns, and they oversaw the treasury. Would Athens lead a campaign or enforce a policy against which they voted? Would the allies craft a policy or devise a strategy without knowing beforehand to what Athens might commit? Could the allies force upon Athens a course of action she did not wish to take?

In the alternative view, Athens sat as hegemon at one end of a bicameral congress while the autonomous allies comprised the other end. The Delian League existed as essentially a compact between two parties, Athens and then the rest of the allies collectively. Each of the two parties thus swore to have the same friends and enemies, but the allies did not swear to follow Athens whithersoever they might lead. In short, neither party could force decisions on the other.

Regardless which form the Delian League's synods ultimately took, the actual practice became the same; the preponderance of Athens existed from the outset, and its commanding influence would grow over the years while allied contributions dwindled, until the allied synods disappeared without any official record of their cessation.

On the other hand, the Delian League did not suffer defections on the brink of campaigns, and it forbade private wars amongst its members. Since its operations also required a constant and continuous active naval fleet for an indefinite period, the alliance demanded a well-organized bureaucracy to collect and dispense regular payments. Athens soon wielded the mechanisms needed to guarantee all League decisions to fruition. The Delian League thus possessed one enormous advantage over the Boeotian Confederation or the Peloponnesian League; it could act swiftly and decisively with considerable resources.

INITIAL OPERATIONS OF THE LEAGUE

The first phase of the Delian League's undertakings begins with its opening operations against the Persian Empire and ends with the decisive Greek victory over Persian forces at Eurymedon (roughly 479/8-465/4 BCE). The League pursued vigorous objectives against Persian encroachments about the Aegean: united – or cooperative – Greek military campaigns, led primarily by the Athenian Cimon, son of Miltiades, both recovered Persian-dominated poleis as well as freed areas of Northern Greece and Asia Minor.

Nevertheless, the League's first ominous signs of internal disagreements and fractures as well as the willingness of Athens to champion and then use compulsion against other members also appeared during this very early time. The League elected first to capture both Eion, a strategically located polis along Xerxes' invasion route, and the island of Skyros. By ejecting the Dolopian pirates based on Skyros, moreover, the League also "liberated the Aegean" (Thuc. 1.98.1; Diod. 11.60.2; Plut. Vit. Cim. 8.3-6). Subsequent League campaigns successfully drove Persian garrisons from Thrace and Chersonesus and expanded Hellenic holdings along the western and southern coasts of Asia Minor (Ionia and Caria areas).

Consequently, the opening years of the League's existence reaped enormous benefits for the smaller poleis about the Aegean, especially the islands. Maritime trade increased substantially, and the constant naval operations provided well-paid service for Greeks from the poorer poleis. Membership in the League soon increased to almost 200 poleis, but the alliance also openly coerced Carystus (on the southern tip of Euboea) to join c. 472 BCE. Carystus possessed a tarnished reputation as a Mede sympathizer during the Persian Wars and had desired to remain neutral and not pay tribute. The Athenians argued that no polis should benefit from the League without sharing in the cost. The bulk of the League agreed.

THE REDUCTION OF NAXOS

The island of Naxos, for reasons unknown, attempted to secede from the alliance c. 467 BCE. Its subjugation produced a change in membership not anticipated during the formation of the alliance. The Athenians "besieged and reduced them. Naxos … [thus became] the first allied polis enslaved contrary to the original structure of the League" (Thuc. 1.98.4). The majority of League members nonetheless appear to have understood that they could not tolerate unilateral defections or rebellions, otherwise the League itself would soon disintegrate and destroy any benefits won.

The oaths of allegiance would now include a new word, obedience. The subjugation of Naxos, in other words, established a precedent, which the Athenians would use for the rest of the League's existence; the use of force to insure compliance.

BATTLE OF EURYMEDON

Cimon continued to lead a Delian League force of 300 triremes in the east: 200 Athenian with 100 allied contingents. He sailed along the Caria and Lycian coasts, sacking and reducing some poleis, driving Persian garrisons out of others, and brought many of these poleis into the League. He relentlessly pursued the Mede.

The Persians assembled a large Phoenician fleet near Cyprus. Cimon collected his forces at the Triopian promontory. After taking Phaselis, he sailed directly for the Eurymedon river in Pamphylia then immediately attacked and defeated the Phoenician fleet as well the reinforcements sent from Cyprus – destroying or capturing almost 200 ships. This victory proved definitive.

This article is part of a series on the Delian League:

- The Delian League, Part 1: Origins Down to the Battle of Eurymedon (480/79-465/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 2: From Eurymedon to the Thirty Years Peace (465/4-445/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 3: From the Thirty Years Peace to the Start of the Ten Years War (445/4–431/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 4: The Ten Years War (431/0-421/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 5: The Peace of Nicias, Quadruple Alliance, and Sicilian Expedition (421/0-413/2 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 6: The Decelean War and the Fall of Athens (413/2-404/3 BCE)