The Sun Dance is a ritual ceremony observed by the Plains Indians of the regions of modern Canada and the United States to awaken the earth, renew the community, give thanks for the sun, and petition or give thanks for favors from the Great Spirit. The ceremony's focus is on gratitude and self-sacrifice for the greater good.

It is one of the seven sacred rites of the Sioux nation and a vitally important ceremony of the people of the Plains generally. Its origin is unknown, but some scholars, including Michael G. Johnson, believe the ritual's most common form was inspired by the Mandan Okeepa (Okipa) Ceremony, a New Year's observance intended to reawaken the natural world after winter and ensure a prosperous harvest and large herds of buffalo (bison), the animal that provided the Plains Indians with food, hide for clothing and shelters, tools made from bones, among other uses, and was also considered a sacred gift from the gods.

The duration of the Sun Dance varied from nation to nation but generally lasted between four days and two weeks, during which young men engaged in ritual dances and tests of physical endurance (including self-torture) to honor the Great Spirit, the gifts of the natural world, and to reawaken the earth and revitalize the community. Scholar Adele Nozedar writes:

Among the Plains Indians one particular ceremony took precedence over all others: the Sun Dance. It was performed by the Arapaho, the Assiniboin, the Blackfeet, the Cheyenne, the Crow, the Dakota, the Kiowa, the Mandan, the Omaha, the Ponca, the Shoshone, the Siksika, and the Ute. For the peoples who practiced it, the Sun Dance had variations, but for all of them the essence of the dance was the very serious fulfillment of a promise made to the Great Spirit in return for a blessing of some kind – for example, victory in battle, or the restored health of a friend or family member. (457)

The Sun Dance was not only a thanksgiving ceremony, however, but was understood as the peoples' duty to their Creator. The Great Spirit had given them all the necessities of life and, by performing the Sun Dance, they were giving back in grateful acknowledgment while also participating in the work of the Creator by awakening the created world through song, dance, and sacrifice.

A temporary lodge was built for the festival, which encouraged communal unity by involving everyone in the village in different roles and for various tasks. In preparation for and, for some, during the ceremony, the people would fast and pray for the good of the community, for individual needs, for visions, for the continued bounty of the world, and in thanks for gifts given. The lodge served as the central staging area of the ceremony and, at its conclusion, was dismantled except for the center pole, left as a reminder of that year's event.

The United States government outlawed the Sun Dance in 1881-1883 and the Canadian government in 1882 as part of the policy of suppressing Native American culture and breaking communal unity. The ritual continued to be observed in secret by the Sioux and other nations until the bans were lifted in the 1950s. Today, the Sun Dance is still observed by the people of the Plains Nations as it was in the past, though without the element of self-torture.

Origin & Seven Sacred Rites

The origins of the Sun Dance are unknown, but, as noted, some scholars have suggested the later form of the ritual came from the Mandan festival. Johnson writes:

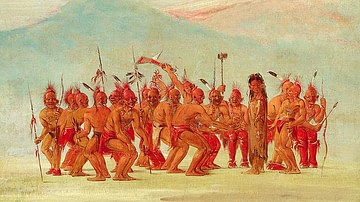

The Sun Dance was probably related to the Okeepa ceremony vividly described by the artist explorer George Catlin in the 1830s. It [the Okeepa ceremony] centered on "Lone Man," who restored the earth after a great flood by use of the "Big Canoe" or ark of wooden planks symbolically representing a protective wall. The ritual was a cosmic new year ceremony to ensure abundance of bison and a new beginning, involving collective – as opposed to individual – vision quests, and spiritual instruction and initiation for youths. Both rituals communicated an idea of a unified religious universe. (96)

George Catlin (l. 1796-1872) was a lawyer-turned-artist who traveled around the North American frontier in the 1830s, chronicling the lives of the Plains Indians in portraits and writings. He describes the Okeepa ceremony as beginning with the construction of a temporary lodge, while those who were to participate fasted for four days and also denied themselves drink or sleep. The ceremony began with a dance to summon the buffalo, and then the fasters were led to the lodge, which was open at the top, where they positioned themselves to look up at the sun through the opening.

Their chests were pierced, and pegs of wood were inserted, which were attached to ropes. As they gazed up at the sun, other participants hoisted them into the air where they remained suspended, still keeping their gaze on the sun, until the pegs tore through their flesh and dropped them to the ground or they fainted and were lowered down. The combination of fasting, lack of sleep and drink, and extreme physical pain combined to produce visions, which were understood to be of benefit not only to the participant but also to the entire community. The ceremony ended with the fasters participating in an endurance race and, presumably, sharing their visions with the medicine men (shamans), who would then share them with others.

A version of the Okeepa ceremony is depicted in the 1970 film A Man Called Horse. The details of this ceremony differ from the Lakota Sioux, the Hidatsa, Cheyenne, and others, but the basic form and focus are the same: giving thanks, self-sacrifice for the good of others, celebrating renewal and new beginnings. The Mandan were related to the Hidatsa, Lakota Sioux, and others through the Siouan language but were a distinct nation with their own rituals and calendar of observances, the Okeepa festival being the most important. The Sioux included their version of the ceremony in the seven sacred rites observed to honor Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit (or Great Mystery) throughout the year:

- Keeping of the Soul (retaining the soul of the deceased until the proper time for its release to the spirit world)

- The Purification Rite (purifying oneself in preparation for a vision quest)

- Crying for a Vision (actively working toward a vision quest)

- The Sun Dance (celebrated to awaken the earth after winter and give thanks)

- The Making of Relatives (entering into pacts of friendship)

- The Girl's Coming of Age (a young girl's puberty ritual)

- The Throwing of the Ball (a ritual symbolizing Wakan Tanka's relationship to the people, harmony, and balance)

It may be that the Sun Dance originated with the Okeepa ceremony, but it is also possible they both came from the same source. Among the Sioux, all seven sacred rites held equal weight in importance, but the Sun Dance was especially significant because it involved the people directly in the annual renewal of the world. The Sun Dance also involved the whole community on many different levels, encouraging bonds of friendship, family, and individual sense of purpose, and drew those related by language or blood from other villages as spectators or participants.

Preparation

The preparation for, and enactment of, the Sun Dance differed from nation to nation but, generally, included many of the same aspects. The ritual was initiated by someone (usually a man) who had received a vision telling them to do so or to make a sacrifice in hopes of answered prayers or to give thanks for prayers answered or as a communal offering for the prosperity of the village, abundant harvests, and plentiful buffalo. It usually took place in early summer, around June, and began with instruction of the participants by the wisemen of the village (medicine men/shamans), who taught the young men the sacred songs, dances, and purification rites.

While this was going on, people from surrounding villages would arrive and a tree (usually a cottonwood) was cut down to serve as a central pole. Other posts were then arranged in a circle around this pole, which represented the connection between Earth and Sky (serving as the sacred World Tree), and then saplings were used (tied between the top of the central pole and surrounding poles) to make the lodge that was enclosed with a roof and walls of buffalo hides. A notable hunter of the village was sent to kill a buffalo with a single shot, and the head or skull of the buffalo (sometimes the hide) was affixed to the top of the center pole.

Leather strips (or ropes) were attached to the top of the pole, later to be used by the dancers. The entrance of the lodge faced east toward the rising sun. An altar was constructed inside the lodge directly across from the entrance, and logs were placed vertically on either side of the central pole, dividing the interior between the drummers, singers, and spectators and the sacred ground of the altar where the participants would be dancing, and the medicine men (or man) would be directing the ritual at the altar. Some tribal nations built the lodge with an opening at the top above the center pole/buffalo head, sometimes the interior was completely enclosed.

Sun Dance

The dancers, who would be participating directly, would fast, pray, abstain from water or sleep, for a certain number of days before the ceremony, and purify themselves. The ceremony began with a formal procession of the medicine men, medicine women, male singers, female singers, drummers, and dancers, followed by spectators, to the lodge. The dancers would have painted themselves white to symbolize purity of spirit and would carry 'medicine bundles' – an animal skin containing objects of spiritual power – and sage. Once inside the lodge, they would choose a spot on the south side to lay their sage and hang their medicine bundle. Sometimes the lead medicine man would initiate the ritual by saluting the spirits with a scalp recently taken in combat from an enemy. The ceremonial pipe (chanunpa) of sacred tobacco (known as lela wakan = "very sacred") was lighted by the lead medicine man, offered to the four cardinal points and the Great Spirit, and then to his colleagues.

Male and female singers and drummers positioned themselves on the south side of the lodge to the left of the entrance and a fire was lighted to the east of the central pole. The dancers, standing on the sacred ground, would raise and lower themselves on their toes while gazing either at the sun through the opening at the top of the lodge or at the buffalo head. The spectators would be the last to enter and would stand or sit to the right and left of the entrance. Dancers would then offer food to the relative or relatives of their fathers in the audience (or this was done earlier). With the fire burning, and everyone in place, the drummers would begin and then the singers would start the sacred songs as the dancers began their dance.

As noted, there were different forms of the Sun Dance (some referred to as the Sun Vow) such as the one depicted in A Man Called Horse when the main character, a white man, joins the Sioux by participating in the rite. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman describes another version of the Sioux ceremony, differing from the depiction in the movie:

Around the pole the male dancers would perform until they collapsed in a frenzied trance or from sheer exhaustion. Most dances are long ordeals. The warriors fast and dance around the sacred tree for hours each day. On the last day, those dancers who have opted for self-torture are attached to the tree by leather thongs tied to wooden skewers that are pushed through deep gashes in the flesh of their chest, back, or shoulders. They must endure this agony throughout the twenty-four songs of the dance, which takes several hours. At the climax of the dance, the exhausted dancers lean outwards to put the maximum strain on the skewers until they rip from their torn flesh, symbolizing a release from the bonds of ignorance. A dance is considered to be successful if a participant experiences a trance or vision during his protracted ordeal. Some devotees also used the skewers to drag heavy buffalo skulls around the camp circle. Warriors would stand or dance for hours, even days, staring into the sun. Participants in the ritual gained great prestige, especially among the Lakota, and warriors would display their Sun Dance scars proudly for the rest of their lives. (234)

Scholars Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark give the Hidatsa version of the self-torture aspect of the ritual:

Two small slits were cut in the shoulder skin, a leather thong was threaded with a wooden pin attached to the end, preventing the thong from pulling out of the slotted skin. The other ends of these thongs were attached to the top of the sun-pole (similar to a Maypole). The Priest and Singer twirled each Faster [Dancer] four times, his feet barely touching the ground, then the Faster swung free, twisting and circling around the sun-pole. But he dared not touch the thong with his hands…When the Faster finally broke loose from the sun-pole, he fell to the ground. Priest and Singer placed him gently on his bed of healing sage. There he remained and fasted from two to four days…They have dreams and visions which they related to the Priest. If they were sufficient, the Faster left the Sun-Lodge because his supplications were answered by the Sun-God (197-198)

The ceremony usually lasted four days but the entire festival might last two weeks or more. Johnson notes:

In both the preliminary and public phases of the rite, lesser ceremonies would interwork. These included male and female initiation into societies, the curing of the sick, exhibitions of supernatural power, the recounting of warrior deeds and the distribution of wealth. (95)

When the ceremony was over, the lodge was dismantled except for the central pole which was left as a reminder of the event, the sacrifices made, visions shared, stories told, and bonds formed.

Conclusion

There is no record of how long the Sun Dance ceremony had been observed by the Plains Indians before the arrival of the Europeans in North America but in the 19th century, as American expansionist policies encouraged settlement further and further west, the immigrants were brought into closer contact with the people of the Plains and found the Sun Dance, especially the self-torture aspect, objectionable. Zimmerman writes:

In the nineteenth century, white observers were shocked by the self-torture associated with the Sun Dance, and in 1881 the practice was outlawed, partly because it was viewed as a focus of resistance to government policies. This was a great blow to the Plains Indians, who believed that without this essential element [of self-torture] the Sun Dance would not be effective, and the world would not be renewed. Afterwards, some Indians took to performing public Sun Dances for white people, simulating the piercing of the flesh by using harnesses. However, many other groups continued to hold traditional dances in secret, complete with the piercing, while lookouts kept watch for officials. (234)

Organizing and participating in the Sun Dance in Canada and the United States was illegal from the 1880s to the 1950s. The law was changed in Canada in 1951 and in the United States in 1934, with restrictions, and then again in 1958, allowing Native Americans the right to practice their religion without fear of persecution or incarceration. In the United States, full rights for Native Americans to observe their religious rituals were not granted until 1978 through the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. The Sun Dance was revived publicly by some nations in the 1960s, by others later, and is now observed annually in Canada and the United States.