The Social Contract is an idea in philosophy that at some real or hypothetical point in the past, humans left the state of nature to join together and form societies by mutually agreeing which rights they would enjoy and how they would be governed. The social contract aims to improve the human condition by establishing an authority based on consent which protects certain rights and punishes those who infringe on the rights of others. Although some philosophers deny such an event has ever occurred, the idea was attractive to some thinkers, particularly during the Enlightenment, as a way to justify citizen participation and promote the advantages of one type of government over another.

State of Nature

The idea of citizens joining together to form a social contract involves an examination of human nature and what sort of state people were in prior to making such an agreement. This pre-societal state is often termed the state of nature. The social contract is created when people decide to leave the state of nature and govern themselves while abiding by certain rules, which guarantee certain rights. The citizens may have to give up certain individual freedoms so that they might enjoy other freedoms and personal safety.

Although philosophers since antiquity have entertained the idea, it was three Enlightenment thinkers, in particular, who made the ideas of the state of nature and a social contract integral parts of their philosophy: Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), John Locke (1632-1704), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Such ideas may never have been realised in practice, but the state of nature and social contract remain useful constructs to facilitate the discussion of which rights citizens should maintain in contemporary political society and how governments should protect these rights. Ideas on the state of nature also allow for a discussion of human nature, which then affects what sort of government might be necessary.

Hobbes' Social Contract

For Hobbes, humans in the state of nature are concerned with one thing only, their self-preservation. As there is, Hobbes says, a perpetual fear that somebody else will do one harm, people pre-empt this by first doing harm to others. This tendency leads to a state of constant warfare or what Hobbes more specifically defined as the perpetual threat of violence. His pessimistic view of humans in the state of nature is summarised in the famous phrase: "the life of man [is] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short" (Leviathan, ch. 13). Humans, then, are obliged to come together and form societies in order to avoid this awful state of affairs. The citizens agree to form a 'covenant' between themselves (not between themselves and a government, which is a different idea). They give up their absolute freedom in the state of nature in order to gain greater protection. The people must give up their free will to the state.

Hobbes believed that humanity's ruthless self-interest necessitated a very strong political authority, which he called Leviathan (after the sea monster in the Bible's Book of Job) and which was the title of his most famous work, published in 1651. This supreme authority, which Hobbes envisions as an absolute monarch, would act in the best interests of all and ensure everyone follows the rules of society. Hobbes believed that a system of monarchy is better than one based on the aristocracy or a democracy. Hobbes does limit the sovereign's power to political and legal matters since he does not advocate they interfere in other areas like the arts. There is, then, even for Hobbes, hope that humanity can live together in relative peace, especially since the alternative is the rampant warfare of the state of nature.

Critics of Hobbes point out that his view of human nature is too pessimistic and that the state of nature is not as bad as he claims, which means that political institutions are under a much greater obligation to provide a fairer and safer society in which to live, a greater obligation than perhaps Hobbes allows for. Others point out that the whole thing is a fiction anyway. Still others are sceptical that if humans are as self-interested as Hobbes claims, then why would they ever form a social contract and willingly give up some of their rights? Hobbes does say that some rights are never given up to the sovereign power, for example, a citizen can refuse the sovereign if they are requested to harm themselves physically or give testimony against themselves in a court of law. Aristocrats did not like Hobbes' social contract as it put everyone on an equal footing in terms of their birthright. Another critical group was Christians who did not take kindly to Hobbes' insistence that religious institutions had no right to meddle in politics. Finally, one noted philosopher pointed out that life for some under a despotic ruler, especially for a minority group, was no improvement on living in a state of nature. This critic was John Locke.

Locke's Social Contract

The English philosopher John Locke published Two Treatises on Government in 1689. Locke here presented the idea that in the state of nature, humans were capable of working together by following the universal law that "no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions" (quoted in Popkin, 77). Although humans are self-interested, Locke believed we have a natural self-restraint. We also use reason to ensure that everyone pursues a common good. Locke also disagreed with Hobbes' view that people did not have any rights to property in the state of nature, and this is why he is keen to protect this right in the social contract. To attack, reduce, or remove a person's property was the same as assaulting that person, which is why Locke also includes the right to life and liberty within the umbrella term 'property'. Rights enjoyed in the state of nature must be guaranteed in the social contract and can never be withdrawn (unless the common good is at stake). Further, because everyone has equal rights in the state of nature, so everyone should have equal rights in a political society.

For Locke, because people willingly create a social contract, the function of government is to serve the people and not itself. Governments are created by the people and with their consent to protect their rights. Individuals are more important than institutions. Locke did not require as strong a government as Hobbes devised. He believed that the 'people' should rule for the simple reason that this is far less likely to end in authoritarian and despotic rule than a government ruled by a monarch alone or a small elite group. Any government that does not fulfil its function can be legitimately overthrown and a new social contract drawn up. To avoid the real danger of governments becoming despotic, there should be a separation of power between the executive (monarch), legislative (upper and lower houses of parliament), and federative (which deals with foreign policy). A fourth branch, the judiciary, is there to punish anyone who breaks the law. A government should foster good behaviour in its citizens through education, bringing out people's natural tendency to do good. Locke calls for the toleration of religious views (except for Catholics since they swear allegiance to a foreign power, the Pope) because these have nothing to do with one's role as a citizen.

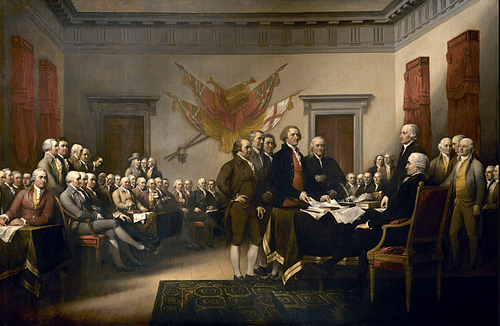

Many of Locke's ideas greatly influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States, but his work did receive some criticisms besides those also directed at Hobbes, that a state of nature and a social contract are mere figments of the imagination. Locke's system still does not seem to protect the minority, which means they may as well be back in the state of nature. In terms of rights, some thinkers have pointed out that the relationship between rights and the common good is not clear. Sometimes these must conflict (e.g. my property right to own a dangerous weapon which could be later misused to infringe another person's right of property), and so some rights are not absolute but carry conditions. The debate would then have to be what conditions exactly do some rights carry?

Rousseau's Social Contract

In his Second Discourse of 1755, Jean-Jacques Rousseau investigated the origin of society's obvious inequalities. He saw the state of nature as entirely primitive, a place where there were no such things as property ownership, pride, and envy since these only arrived in humanity when they began to form societies. He suggests that humans in a state of nature are free, equal, and have two basic instincts: a sense of self-preservation and pity for others. As humans gathered together in more sophisticated societies, so their morality declined. The pursuit of self-interest and wealth takes over. Society is corrupt, unequal, and morally bankrupt. Civilized humans are unhappy, selfish, and unfree. This all makes for rather a bleak picture of humanity.

Rousseau does offer hope. His plans for a fairer society are laid out in his Social Contract, published in 1762. In Rousseau's ideal society, no person should ever have to sell themselves, and no rich person should ever be able to buy another person. His ideal government is concerned with limiting the excesses of inequality (he recognises absolute equality is impossible). People must gather in a community based on consent and form a social contract between themselves, with the ultimate objective of that society being the common good.

Rousseau believes that an aristocratic, or more precisely, elitist government (since he does not agree with a hereditary nobility) is better than a monarchy (which can become despotic) or democracy (which is too troubled by factions). Rousseau's ideal government is not a representative one, since he believes those who govern should be elected but only to carry out administrative tasks, its primary role. The general will (in some way that is not made clear) chooses what is best for the state as a whole, and the governors merely put the general will into practice. In this way, Rousseau separates sovereignty from government.

The idea of a general will is then crucial to Rousseau's social contract. Laws and strong government are required to guide the general will of the people when it might otherwise err. For Rousseau, the general will is the result of a compromise where individuals sacrifice complete liberty to achieve the next best option: a restriction on liberty in order to avoid a situation of no liberty at all. The general will, then, is not merely the sum of each individual's will but, rather, the best interests of society as a whole. For example, if asked what rate of tax they would like to pay, most people would choose as little as possible, even 0%. This rate, however, would make it impossible for the state to function, and so the general will in this case is to implement the best tax rate to provide the state services required. For Rousseau, the logical conclusion of this approach is that whatever the general will turns out to be, that is the right one. The consequence of this infallibility, as some critics have pointed out, is that Rousseau's government has tremendous power since the state is, in effect, allowed to force people to be free. Rousseau explains that this is not as bad as it sounds, what is really happening is the state is educating its citizens to become self-disciplined, and so free. The second role of government, then, is to educate the people to reduce their tendency to act with self-interest.

A third role of government is to protect property, for Rousseau an unfortunate creation of society. Property, perhaps gained illegitimately in the state of nature, is now being protected by law. Rousseau saw this as unfair on those without property, and so the social contract is much more beneficial to the richer elements of society. Like Locke, Rousseau points out that should citizens become too disadvantaged, then they have a right to overthrow their government since the social contract has been broken. The social contract is, then, far from perfect, but other philosophers had much more serious objections to the very idea of such a contract.

Legacy & Criticisms

The philosophical discussion of which rights people possessed in the state of nature influenced ideas on which of those rights should be protected by governments, as we have seen. This was not just in theory but also in practice. The clearest example is in the United States when the 13 British colonies declared independence and drew up their own and entirely new constitution in 1789. Many of the ideas in this constitution, as well as in the Bill of Rights, were inspired by the ideas on liberty and happiness presented by such thinkers as Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. Another group of revolutionaries influenced by these new ideas on a social contract and government through consent was the rebels of the French Revolution (1789-99). Social contract theory has continued to greatly influence both liberal and conservative political theory.

There have been serious criticisms of the idea of the social contract. Philosophers like David Hume (1711-1776) and Jeremy Bentham (1747-1832) did not believe such a thing as a state of nature or a social contract ever existed. Hume noted:

Almost all the governments which exist at present, or of which there remains any record in story, have been founded originally, either on usurpation or conquest, or both, without any pretence of a fair consent or voluntary subjection of the people.

(Gottlieb, 130)

Other thinkers like Voltaire (1694-1778), Montesquieu (1689-1757), Giambattista Vico (1668-1744), and Adam Ferguson (1723-1816) have all suggested that the social contract idea is defunct because humans cannot exist outside of some sort of society, the most basic form being the family. Some social contract theorists might counter that they are not actually suggesting such a thing as the state of nature ever existed but are merely using the idea, and the idea of a social contract, to promote their view of the best and most stable type of government. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) took just this hypothetical approach to the social contract, noting "we need by no means assume that this contract…actually exists as a fact…It is…merely an idea of reason, which nonetheless has undoubted practical reality…[it] is the test of the rightfulness of every law" (Gottlieb, 132).

Hume stated additional criticisms. First, that even if a social contract had once been drawn up between citizens, this did not mean that today's generation should in any way be bound by such an agreement. For, such a contract "being so ancient, and being obliterated by a thousand changes of government and princes, it cannot now be supposed to retain any authority today" (Gottlieb, 131). Locke and others counterargue that by stating their belief that if one decides to stay in the state one is born, then one gives consent to its government. Adam Smith (1723-1790) pointed out that this rather weak argument of defining consent, as not protesting the absence of one's consent means that if you were brought on to a boat while asleep and it then sails off across the ocean, one gives one's consent to being there even though there is nowhere else to go. Hume, rather, prefers to legitimise government institutions not by imagining a specific past agreement to them by the citizens but through the fact that they have stood the test of time to become established conventions. A second criticism of Hume's regarding the social contract is that he did not believe that a failing government justified the citizens rebelling or overthrowing it.

The idea of the social contract fell out of favour in the 19th century. Bentham thought that it entirely distracted from other ways of examining the value of laws (in his case, the happiness of the greatest number was the main criterion). Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) thought that all rulers seize power and are never willingly given it. Philosophers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) and Karl Marx (1818-1883), thought the state of nature, and consequently a social contract, useless constructs because they viewed human nature as a product of society, a fact established by sociobiology. Nevertheless, other thinkers, notably John Rawls (1921-2002), have continued to find at least the hypothetical notion of a social contract (what Rawls calls the "original position") a useful tool to imagine exactly which rights and political systems an impartial and rational citizen would themselves choose to support if they were given a choice and if they did not know how those laws might personally affect them. Further, the social contract idea continues to be useful to address continuing concerns over how citizens with different objectives can be reconciled within the same society and how can minority groups have their interests protected when the majority might only seek to protect themselves.