Enki's Journey to Nippur (c. 2000 BCE) is a Sumerian origin myth explaining the creation of the temple at Eridu by the god Enki and how musical instruments were ordained for use in festivals in ancient Mesopotamia. The poem formed part of the Decad (ten compositions of advanced study) in Mesopotamian education.

The piece (also known as Enki Builds E-engura and Enki's Journey to Nibru) describes Enki's creation of the E-engura (temple), praise for his work as given by his minister/servant Isimud, the finished work, and Enki's trip to Nippur (also known as Nibru) where he hosts a drinking party to celebrate his accomplishment and receives the blessings of the god Enlil. Although the title suggests the piece will focus on the journey, that part of the story only appears in the last 33 lines.

The poem was found in the ruins of the city of Nippur (in modern-day Iraq) in the mid-19th century and the ruins of Ur in the early 20th century, the later find adding to the broken tablet discovered at Nippur. The work is important as a Mesopotamian charter myth (creation or origin myth) on the creation of Enki's temple, alcohol as part of religious celebrations, and the importance of musical instruments in religious festivals but also for its contribution to modern scholarship concerning the curriculum of the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the Mesopotamian scribal school.

Further, the poem suggests the common motif of ancient religious literature of a god creating something from nothing and, often, through the power of speech. In Enki and the World Order, the god creates the world by speaking it into existence and this seems to be the same with Enki's Journey to Nippur, even though it is not as explicitly stated. This motif is thought to have influenced later works, including the first chapter of the Book of Genesis in the Bible.

Enki & The Edubba

Enki was the Sumerian god of wisdom, intelligence, trickery and mischief, crafts, magic, exorcism, healing, creation, virility and fertility, art, and freshwater. Although the myths in which he features cover aspects of all of the above, he was primarily associated with freshwater and wisdom as noted by scholar Stephen Bertman:

Enki's domain was the Abzu (or Absu), an ocean of freshwater upon which the earth floated, and which served as the life-giving source of streams and rivers. Because of water's secret and potent source, Enki was associated with arcane wisdom, embodied in both skilled crafts and sorcery. He used his cunning to save mankind before the Great Flood, and he was prayed to by those beset by crisis. His holy city was watery Eridu. (118)

The Sumerians understood Eridu as the oldest city on earth and the site where order, law, and kingship were first established. As the founder of the city, therefore, Enki was among the oldest and most revered of the Mesopotamian pantheon. He was also known by other names including Nudimmud (as given in the poem), Ninsiku, Nissiku, Enkig, and Ea, each used to describe a different aspect of the god or a different culture's name for him.

Enki first appears in Sumerian literature in the Early Dynastic Period III (2600-2334 BCE) under those names except for Ea, which was the name used by the Akkadians from c. 2400 BCE on, and possibly Nudimmud, a Babylonian name. He was the son of the sky god An (Anu), though sometimes referenced (as in this poem) as the son of Enlil, most likely a symbolic term meaning he acted in accordance with Enlil's will. He is usually depicted as an equal or near-equal of Enlil as in the list of the Seven Divine Powers (the earliest Sumerian gods): Anu, Enki, Enlil, Inanna, Nanna, Ninhursag, and Utu-Shamash.

As the god of wisdom and intelligence, Enki was naturally associated with the Mesopotamian scribal schools although, of the many myths in which he features – and which would have been memorized and copied by the scribes in ancient Mesopotamia – only Enki's Journey to Nippur was included as part of the curriculum. Students began their education with simple texts before progressing to the Tetrad (four compositions) and then the more difficult Decad. Enki's Journey to Nippur would have been included for the complexity of the text as well as its content praising Enki as a god of creation.

Summary & Commentary

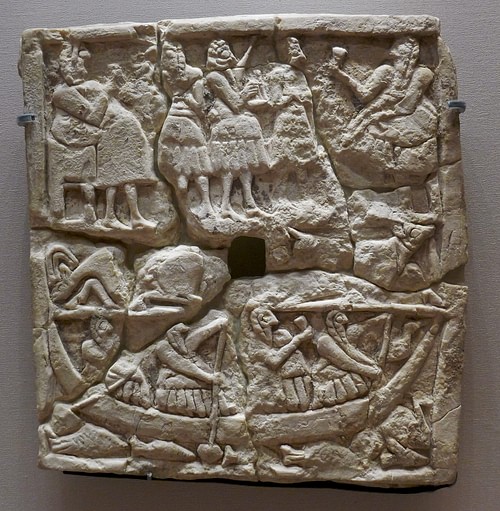

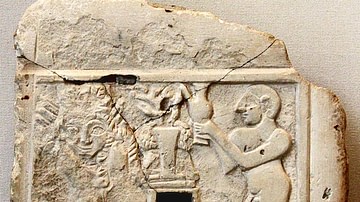

Lines 1-17 describe Enki's creation of the temple at Eridu, which he raises from the abzu and ornaments with silver and lapis lazuli. His minister Isimud then praises his work while describing the temple and listing some of the musical instruments Enki has created for celebrations such as the alijar instrument, the balaj drum, and others (lines 18-70). Following this section, the temple's majesty is emphasized and the drums to be used in festivals – the ala drums and ub drums – are referenced (lines 71-95). Enki then leaves Eridu for Nippur, Enlil's sacred city, where he invites An, the Anuna gods (older deities), and Enlil to a drinking competition to celebrate, and the work ends with praise to Enki (lines 96-129).

This celebration involves only alcohol, no food is mentioned, which is in keeping with Enki's character as a god who regularly enjoyed strong drink but also highlights the festive aspect of the gathering and touches upon the tradition of drinking at religious festivals. Beer was understood as the drink of the gods, and in this poem, they are seen celebrating with only beer and liquor. What was good for the gods was recognized as equally good for humanity, and so the divine drinking competition justified and explained later mortal competitions of the same sort.

The references to musical instruments in the piece are just as important as the description and praise of the temple or the celebration as the author makes clear that Enki created these as well as his new home in Eridu. The instruments, which a Sumerian audience would have recognized as the same played at festivals, are here given a point of origin and a creator. Enki is seen as the architect of both his temple and one of the primary means by which he was worshipped: through music. Scholar Dahlia Shehata comments:

The religious status of a musical instrument is apparent through its occurrences in the written evidence, consisting of literary texts, lexical lists, and administrative documents…Further markers are adjectives like ku/kug "holy; pure" or mah, "great"; however, such classifiers and attributes are not regularly used. Information on the religious status of a musical instrument is more easily inferred from the context in which it appears, whether it is mentioned in mythology, kept in a temple, or worshipped in ways of regular offerings and tended to through special rituals. (Westenholz et al., 103)

Shehata's claim is illustrated clearly in Enki's Journey to Nippur where lines 62-67 show how Enki made the instruments to "offer their best for his holy temple", while lines 93-95 link sacrificial offerings with the installation of the drums. The poem, therefore, would have not only given the origin of Enki's temple at Eridu and alcohol as part of religious celebrations but of the instruments played and heard at festivals staged in his honor.

Text

The following is taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al., and from The Electronic Corpus of Sumerian Literature, translated by the same. Ellipses indicate missing words or lines, and question marks an alternate translation for a word.

1-8: In those remote days, when the fates were determined; in a year when An brought about abundance, and people broke through the earth like herbs and plants – then the lord of the abzu, king Enki, Enki, the lord who determines the fates, built up his temple entirely from silver and lapis lazuli. Its silver and lapis lazuli were the shining daylight. Into the shrine of the abzu he brought joy.

9-17: An artfully made bright crenellation rising out from the abzu was erected for lord Nudimmud. He built the temple from precious metal, decorated it with lapis lazuli, and covered it abundantly with gold. In Eridu, he built the house on the bank. Its brickwork makes utterances and gives advice. Its eaves roar like a bull; the temple of Enki bellows. During the night the temple praises its lord and offers its best for him.

18-25: Before lord Enki, Isimud the minister praises the temple; he goes to the temple and speaks to it. He goes to the brick building and addresses it: "Temple, built from precious metal and lapis lazuli; whose foundation pegs are driven into the abzu; which has been cared for by the prince in the abzu! Like the Tigris and the Euphrates, it is mighty and awe-inspiring (?). Joy has been brought into Enki's abzu.

26-32: "Your lock has no rival. Your bolt is a fearsome lion. Your roof beams are the bull of heaven, an artfully made bright headgear. Your reed-mats are like lapis lazuli, decorating the roof-beams. Your vault is a bull (some mss. have instead: wild bull) raising its horns. Your door is a lion who seizes a man (1 ms. has instead: is awe-inspiring). Your staircase is a lion coming down on a man."

33-43: "Abzu, pure place which fulfils its purpose! E-engura! Your lord has directed his steps towards you. Enki, lord of the abzu, has embellished your foundation pegs with cornelian. He has adorned you with ... and (?) lapis lazuli. The temple of Enki is provisioned with holy wax (?); it is a bull obedient to its master, roaring by itself and giving advice at the same time. E-engura, which Enki has surrounded with a holy reed fence! In your midst a lofty throne is erected, your door-jamb is the holy locking bar of heaven."

44-48: "Abzu, pure place, place where the fates are determined – the lord of wisdom, lord Enki, (1 ms. adds the line: the lord who determines the fates,) Nudimmud, the lord of Eridu, lets nobody look into its midst. Your abgal priests let their hair down their backs."

49-61: "Enki's beloved Eridu, E-engura whose inside is full of abundance! Abzu, life of the Land, beloved of Enki! Temple built on the edge, befitting the artful divine powers! Eridu, your shadow extends over the midst of the sea! Rising sea without a rival; mighty awe-inspiring river which terrifies the Land! E-engura, high citadel (?) standing firm on the earth! Temple at the edge of the engur, a lion in the midst of the abzu; lofty temple of Enki, which bestows wisdom on the Land; your cry, like that of a mighty rising river, reaches (?) king Enki.

62-67: "He made the lyre, the aljar instrument, the balaj drum with the drumsticks (some mss. have instead: the lyre, the aljar instrument, the balaj drum of your sur priests) (1 ms. has instead: your lyre and aljar instrument, the balaj drum with the drumsticks) (1 ms. has instead: the lyre, the aljar instrument, the balaj drum and even the plectrum (?)), the harhar, the sabitum, and the ... miritum instruments offer their best for his holy temple. The ... resounded by themselves with a sweet sound. The holy aljar instrument of Enki played for him on his own and seven singers sang (some mss. have instead: tigi drums resounded)."

68-70: "What Enki says is irrefutable; ... is well established (?)." This is what Isimud spoke to the brick building; he praised the E-engura with sweet songs (1 ms. has instead: duly).

71-82: As it has been built, as it has been built; as Enki has raised Eridu up, it is an artfully built mountain which floats on the water. His shrine (?) spreads (?) out into the reed-beds; birds brood (1 ms. adds: at night) in its green orchards laden with fruit. The suhur carp play among the honey-herbs, and the ectub carp dart among the small gizi reeds. When Enki rises, the fishes rise before him like waves. He has the abzu stand as a marvel, as he brings joy into the engur.

83-92: Like the sea, he is awe-inspiring; like a mighty river, he instils fear. The Euphrates rises before him as it does before the fierce south wind. His punting pole is Nirah (some mss. have instead: Imdudu); his oars are the small reeds. When Enki embarks, the year will be full of abundance. The ship departs of its own accord, with tow rope held (?) by itself. As he leaves the temple of Eridu, the river gurgles (?) to its lord: its sound is a calf's mooing, the mooing of a good cow.

93-95: Enki had oxen slaughtered, and had sheep offered there lavishly. Where there were no ala drums, he installed some in their places; where there were no bronze ub drums, he dispatched some to their places.

96-103: He directed his steps on his own to Nippur and entered the Giguna, the shrine of Nippur. Enki reached for (?) the beer, he reached for (?) the liquor. He had liquor poured into big bronze containers and had emmer-wheat beer pressed out (?). In kukuru containers which make the beer good he mixed beer-mash. By adding date-syrup to its taste (?), he made it strong. He ... its bran-mash.

104-116: In the shrine of Nippur, Enki provided a meal for Enlil, his father. He seated An at the head of the table and seated Enlil next to An. He seated Nintud in the place of honour and seated the Anuna gods at the adjacent places (?). All of them were drinking and enjoying beer and liquor. They filled the bronze aga vessels to the brim and started a competition, drinking from the bronze vessels of Urac. They made the tilimda vessels shine like holy barges. After beer and liquor had been libated and enjoyed, and after ... from the house, Enlil was made happy in Nippur.

117-129: Enlil addressed the Anuna gods: "Great gods who are standing here! Anuna, who have lined up in the place of assembly! My son, king Enki, has built up the temple! He has made Eridu rise up (?) (1 ms. has instead: come out) from the ground like a mountain! He has built it in a pleasant place, in Eridu, the pure place, where no one is to enter – a temple built with silver and decorated with lapis lazuli, a house which tunes the seven tigi drums properly, and provides incantations; where holy songs make all of the house a lovely place – the shrine of the abzu, the good destiny of Enki, befitting the elaborate divine powers; the temple of Eridu, built with silver: for all this, father Enki be praised!"

Conclusion

The poem is often compared to Enki and the World Order, in which Enki creates the world and civilization following Enlil's rough outline. As in other myths, Enlil's plan is completed (sometimes thwarted, as in the Atrahasis) by Enki who speaks the seen and unseen aspects of the natural world into being. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer comments:

This myth serves as a vivid illustration of the Sumerians' superficial notions about nature and its mysteries. Nowhere is there an attempt to get at the fundamental origins of either the natural or cultural processes; all are ascribed to Enki's creative efforts usually by merely stating what amounts to “Enki did it.” Where the creative technique is mentioned at all, it consists of the god's word and command, nothing more. (122)

While this may be true, it is hardly remarkable or unique to the Sumerians as the creation myths of every ancient civilization follow this same basic paradigm: a god or gods enact creation through speech. There is nothing unusual about this concept from ancient times to the present day as speech can be seen as a creative act, making known what was previously hidden or clarifying what was obscure.

In Enki and the World Order, the god follows this same model of speaking the world into existence and, although speech is not mentioned in the early lines of Enki's Journey to Nippur, it could be assumed he does the same here from line 68 – "What Enki says is irrefutable; is well established" – followed by how Enki raises Eridu up (line 71). An ancient Sumerian audience would not have required from a tale any attempts "to get at the fundamental origins of either the natural or cultural processes" because it was enough to know that their gods were in control, had shown themselves trustworthy in the past, and would continue to in the future. Temples like Enki's at Eridu, and the stories of how they came to be, encouraged this trust and so a religious, cultural, and social unity of belief and resultant behavior.