Sir John Hawkins (1532-1595 CE) was an Elizabethan mariner, merchant and naval administrator who has the inglorious (if not wholly accurate) record of being England's first slave trader. In the 1560s CE Hawkins trafficked slaves from West Africa on three voyages, taking them across the Atlantic for sale to Spanish colonial settlements in the New World and making huge profits for himself and investors who included the Crown. The mariner was involved in the infamous incident at San Juan de Ulúa off Mexico in 1568 CE which began the increasingly sour relations between England and Spain. Later in his career, Hawkins oversaw reforms in the Royal Navy and the construction of the modern and well-armed ships which helped defeat the Spanish Armada of 1588 CE. Hawkins died of illness in 1595 CE on a voyage to the Caribbean to raid Spanish treasure ships and colonial settlements.

The Atlantic Slave Trade

John Hawkins, born in Plymouth in 1532 CE, had trader and mariner blood in his veins, his father being William Hawkins who had traded in Brazil in the 1530s CE. In 1551 CE John married Katherine Gonson, the daughter of the Treasurer of the Navy and so a long association, with that body began. The historian G.R. Elton gives the following description of John Hawkins' character:

…he was a man of commanding presence and intellect, of outstanding abilities as a seaman, administrator, fighter and diplomat, and endowed with such charm that even his opponents in the Spanish colonies could only remark ruefully that once you let Hawkins talk to you you would end up by doing his wlll. (340)

In October 1562 CE John Hawkins led an expedition of three ships (Saloman, Jonas, and Swallow) to Guinea in West Africa where he acquired around 500 slaves for transportation to the Americas. There is evidence that many of these slaves, considered at the time by both buyer and seller as a mere commodity without any human rights, were already slaves of African rulers before Hawkins purchased them. Payment was made using cheap rolls of coloured cloth and other trinkets. An additional number of slaves may also have been already in the hands of Portuguese traders who, ignoring their government's protectionist trade policy, happily sold to a willing buyer there on the spot. Finally, slaves may also have been taken by force from villages by Hawkins' men. The real events of just how all the slaves were acquired are difficult to disentangle from the local official's accounts which were likely doctored to appease higher officials back in Portugal. The same pattern of duplicity would be repeated in the Spanish Americas.

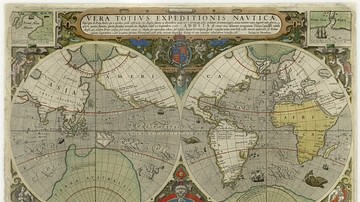

In the New World, the slaves Hawkins transported were sold for use as labour on plantations on Hispaniola (modern Haiti). Two of Hawkins' ships were impounded when they entered Spanish ports in the West Indies, a reminder that Spain controlled trade in this part of the world and did not welcome outsiders, even if Hawkins sought to trade openly with whoever would do business with him. Hawkins may have been many things but he was not a smuggler. Despite the loss of the ships, Hawkins returned to England with bags of cash and a cargo of hides and sugar. The expedition had been funded by a consortium of London bankers and so much money had been made that it was repeated in 1564 CE. Thus the trade triangle was established (West Africa-Central Americas-Western Europe) which in the next decades and centuries would see countless Africans brutally herded from one continent to another for profit.

Second Slave Voyage

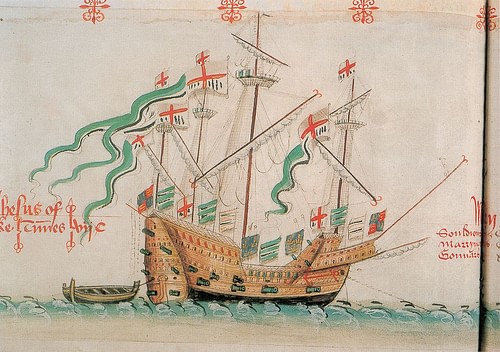

Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) supported this second expedition of Hawkins who was accompanied by his young cousin Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE). The queen even provided the ship Jesus of Lubeck a 700-ton giant but woefully out of condition for a sea voyage. Other investors included Elizabeth's current favourite, the courtier Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (l. c. 1532-1588 CE) and the queen's chief minister, William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1520-1598 CE). Hawkins had become the frontman for a consortium of England's rulers to try and force free trade with the Americas and break Spain's monopoly there. The merchant-mariner repaid this good faith and everyone who invested made a huge amount of cash out of this second trip, about 60% profit on their original investment.

The 1564 CE expedition had repeated the formula of the first expedition, but this time Hawkins captured or simply bought a number of Portuguese ships along the West African coast and, acquiring some 600 slaves through trade with local chiefs and Portuguese traders as before, transported them across the Atlantic and sold them in settlements on the north coast of South America.

Hawkins and the Spanish governors at both Borburata and Curacao colluded to create a story that the English fleet had threatened their settlements if trade had not been conducted, thus once again escaping sanction from the Spanish government. Hawkins received gold and silver for the slaves as well as promises to buy more in the future. Hawkins visited Jamaica and then a Huguenot settlement in Florida on the journey back. The small fleet next took in a stock of fish in Newfoundland before recrossing the Atlantic and returning to Plymouth in September 1565 CE. Richer than ever and with happy investors all around, Hawkins was awarded his own coat of arms which, appropriately enough, included an African slave in chains. This little piece of heraldic history is evidence enough that Hawkins was less a privateer and more an official trade pioneer for the English Crown.

San Juan D'Ulúa

In October 1567 CE Hawkins led a third slave trade expedition. Francis Drake was present again and this time he was made captain of the Judith, a ship of a mere 50 tons. The fleet consisted of six ships and had high hopes of repeating the success of Hawkins' first two voyages. By now, however, the Portuguese were more vigilant along the coast of West Africa to protect their monopoly on the slave trade. Consequently, and unlike in the previous two expeditions, Hawkins could not use established trading partners and was obliged to help an African tribal leader in Sierra Leone to conquer a neighbouring settlement and acquire slaves that way. Only 260 slaves were taken in this raid and Hawkins lost a handful of his own men. A pair of Portuguese ships were attacked for their cargo and another 100 slaves taken. It seemed Hawkins had burnt his trade bridges when he left West Africa for the last time.

Unfortunately for the mariner-entrepreneurs, the expedition met even more problems when it reached the other side of the Atlantic. Satisfactory trade was conducted again at Borburata, but at Rio de la Hacha the Spanish put up armed resistance to these interlopers. Hawkins took over the settlement by force and some trade was then conducted. Next, trade was done amicably at Santa Marta but the governor of Cartagena refused point-blank. The easy willingness to trade of previous expeditions was clearly at an end.

The Spanish had sent a clear message that they would not tolerate outsiders in their lucrative Europe-New World trade circuit, even if their colonies' needs were greater than Spain itself could supply, especially in terms of slaves. However, the Spanish government's stricter control and continued monopoly on trade of all kinds was about to be seriously challenged.

The 'Treasure Crisis'

The attack at San Juan D'Ulúa was bad for Anglo-Spanish relations but across the Atlantic events were unravelling that saw things become much worse between Elizabeth and Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE). This was the so-called 'Treasure Crisis' of 1568 CE. The crisis began in November when five Spanish treasure ships carrying some £85,000 in silver and gold coins were obliged to seek shelter in Plymouth and Southampton harbours following storms and pursuit by Huguenot pirates. This vast sum of cash was on its way to pay Spanish armies in the Netherlands, then under the control of Philip. Given safe harbour, the cargo was brought ashore along with documents stating the cash came from Genoese bankers and did not officially belong to Philip until it reached Spanish-held territory. Elizabeth decided this was a good moment to dent Philip's war chest and so she enquired if the Genoese bankers would not rather lend her the money. The Italians, realising Philip was unlikely now to get his loan, said yes. In retaliation, Philip ordered all English ships and trade goods in the Netherlands to be seized in December 1568 CE. Elizabeth responded by commanding that all Spanish ships and trade goods in English ports be seized. As the tit-for-tat game continued, Philip ordered that no English ships be allowed to trade in the Netherlands, a situation which went on for five years.

It was in the midst of this crisis that Hawkins returned to England. The merchant-mariner likely gained no honour from the debacle of his third voyage, but at least in the present diplomatic circumstances, he was not censored. As yet, neither England nor Spain was willing to go to war over trade issues, but an armed conflict was the ultimate consequence of the ever-deteriorating Anglo-Spanish relations. Hawkins, meanwhile, sank into obscurity for a decade but the coming of this war meant that he received another chance to serve his country.

The Royal Navy

After 1569 CE, then, John Hawkins no longer went to sea on expeditions but became increasingly involved with the English Royal Navy. In 1578 CE (or 1579 or 1580 CE - historians do not agree) he was appointed the navy's treasurer and in this capacity he restructured this still-young institution, improving its organisation and command structures, as well as modernising its fighting tactics. Hawkins knew from experience the value of fast and manoeuvrable ships against larger, slower, and more cumbersome Spanish vessels and so the navy was rebuilt along those lines. Over the next decade, the navy was thus able to boast such fine state-of-the-art vessels as the galleons Ark Royal and Revenge. By the time he was finished, the Royal Navy had 23 sailing ships and 18 pinnaces (smaller vessels useful for close-to-shore work).

Hawkins had also seen for himself that a ship capable of firing a good broadside of cannons was much more effective than the more traditional method of boarding an enemy vessel. In addition, cannons were seated on four-track carriages which speeded up reloading times and meant they could fire heavier shot. Other innovations included creating airier ships to facilitate cleanliness and reduce the terrible toll disease took on naval crews. Flatter sails were adopted which were easier to handle and offered greater speed. He even managed to persuade the government to consent to a pay rise for seamen in the hope of attracting a greater calibre of individual to the service. All of these things were achieved despite limited funds and the hopelessly old-fashioned and practically inexperienced members of the navy board. As Hawkins noted in a private letter, the board members were difficult to manage:

The higher officials who serve in this office have grown so proud, obstinate and insolent that nothing can please them, and the lesser very disobedient, such that a man might prefer to die than to live under the obligation of answering all of their immoderate demands.

(Bicheno, 281)

Hawkins, too, endorsed the policy of privateering, even if a lack of coordination on the part of the English and a greater use of convoys by the Spanish brought ever-diminishing returns.

Spanish Armada

England was threatened in the summer of 1588 CE by the Spanish Armada of Philip II of Spain which he intended to use to ferry an invading army from the Netherlands. Hawkins served as rear-admiral to the English fleet that met this armada and as such was third in command behind Lord Howard and Francis Drake. Hawkins captained the 565-ton carrack Victory but his best contribution to the battle was the design of ships he had been building and their weaponry. The English fleet was immeasurably helped by the bad weather over the duration of the battles in the English Channel but they also had faster ships, were much more nimble and could fire their cannons further than the enemy. Following the victory, Hawkins was knighted by a grateful queen.

1595 CE: Final Expedition & Death

In the early 1590s CE Hawkins took to privateering around the Azores. Then, in August 1595 CE Hawkins and Drake combined to joint-lead a major expedition to the Caribbean. Men flocked to the docks at Plymouth, eager to sign up and sail with two of England's great maritime names. The objective of the 27-ship fleet was to attack the Isthmus of Panama where the Spanish silver caravans passed through. Before that, the Englishmen wanted to capture a disabled Spanish treasure ship undergoing repairs in Porto Rico. Alas, Hawkins died of illness on 12 November on the voyage there, and then the attack on Porto Rico was a complete failure. The Spanish defences had been warned of the English fleet's arrival, giving them time to install extra cannons, and this intelligence also meant no treasure ships risked the area. Beset with unfavourable winds as disease ran through the crews, Drake himself died of dysentery at Portobelo on 28 January 1596 CE. It was the end of an era in English naval history.