Marcus Porcius Cato (95-46 BCE), better known as Cato the Younger or Cato of Utica, was an influential politician of the Roman Republic. As the great-grandson of Cato the Elder and a dedicated student of Stoicism, he believed in traditional Roman values. During the Catiline Conspiracy, he argued for the execution of the conspirators, starting a life-long enmity with Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE).

Although they had been political enemies in the past, Cato sided with Pompey (106-48 BCE) during the civil war between Pompey and Caesar. After the death of Pompey and Caesar's victory at the Battle of Thapsus, he took his own life in Utica.

Family

Born in 95 BCE, Cato the Younger was the great-grandson of Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE), the Censor. Josiah Osgood in his Uncommon Wrath wrote that "Cato the Elder championed traditional Roman values of hard work, austerity, and a willingness to make any sacrifice for the public good" (23). It was Cato the Elder who said during the Punic Wars, "Carthago delenda est!" or "Carthage must be destroyed!" He was a perfect role model for the young Cato. The younger Cato had a brother, Caepio, and a sister, Porcia. With their father and mother both dying early, Cato and his siblings ultimately lived with their mother's brother Livius Drusus on Palatine Hill. Although little is known of his early life, according to Plutarch's Lives, he was considered a dull student, slow to understand, but possessing a remarkable memory.

Stoicism

Through his association with Antipater of Tyre, Cato became a dedicated student of Stoicism and devoted himself to its moral and political doctrines, shunning materialism and living a life of virtue. Plutarch wrote that he was resolute in purpose, and from infancy, he displayed an "inflexible temper, unmoved by passion, and firm in everything" (838). Plutarch added, "He was rough and ungentle toward those that flattered him, and still more unyielding to those who threatened him" (838).

Cato became adept in the art of debating and speaking, and according to those who heard him speak in the Roman Forum or Senate, he had a voice that boomed across the floor. With no sense of humor, he had a rigid commitment to justice. In his Death of Caesar, Barry Strauss wrote that Cato was "loyal to the old-fashioned notion of a free state guided by a wise and wealthy elite" (21). Strauss maintained that Cato was an elitist, looking down on the masses. With typical Stoic resolve, he despised fashion and luxury, often going barefoot as well as wearing a dirty toga.

Military Tribune

Cato's political career would see him serve as a military tribune, quaestor, tribune of the plebs, praetor, and lastly, military commander. Throughout his adult life, he fought to protest improprieties whether in Rome or not. He never resisted confronting anyone he thought acting unjustly. Like the orator and statesman Cicero (106-43 BCE), he was an ardent supporter of the old Republican values and an idealistic defender of the Roman Republic. Strauss claimed Cato was "Brilliant, eloquent, ambitious, patriotic, yet defended freedom of speech, constitutional procedures, civic duty and service" (22). Although never clearly defined, in the days of Cato, Roman politics centered on two factions: the Optimates, who espoused the ideals of the wealthy as well as maintaining reliance on the power of the Roman Senate; and the Populares, who were "men of the people" and supported the popular assemblies.

His first taste of service to the state was when he volunteered to join his brother during the Spartacus uprising. Osgood wrote that he embraced the rigors of camp life, showing both discipline and bravery. When Cato was elected to serve as a military tribune, he was sent to Macedonia where, displaying his Stoic values, he dressed, lived, and marched like an ordinary Roman legionary. He was considered an excellent commander, putting the Roman army ahead of himself, thereby, earning the respect of those under his command. Plutarch said, "…in character, high purpose, and wisdom, he far excelled all that had the name and title of commander" (843). After his year ended, he traveled throughout Asia Minor to observe conditions in various places where unrest had recently occurred, and of course, walking barefoot, not like others in his entourage. Unfortunately, his brother suddenly died of an illness while on an assignment in Asia. Cato arrived too late to be by his side.

Quaestor

In 69 BCE, Cato took his first step on the ladder of the cursus honorum: the quaestorship, serving as the guardian of the treasury. Having studied the office beforehand and understanding his duties, he demanded to see the accounts, immediately finding errors, uncollected debts, and forged documents. Those scribes found guilty of misconduct were dismissed or threatened with prosecution. He demanded that individuals who had profited from Sulla's proscription lists return the reward money. For all those who had committed offenses, trials were held and convictions were secured by the presiding officer, Julius Caesar. People were impressed by Cato's tenacious efforts, but it became obvious to many that Cato and Caesar were destined to clash. Osgood wrote that Cato saw Caesar as "pandering to the people while Caesar saw Cato as blind to the difficulties ordinary Romans faced" (27).

Catiline Conspiracy

One of the most challenging events of Cato's political career was the Catiline conspiracy. Catiline (Lucius Sergius Catilina) was an ambitious politician, but he was bordering on bankruptcy. He had one goal in mind: the consulship. It was something that might possibly help his financial woes. At the time of the election of 64 BCE (for the year of service 63 BCE), Rome was suffering from a financial crisis, affecting the urban poor and rural farmers. Catiline saw it as a tool to win the election. During a fiery speech before the Senate, he called for the elimination of the debts of the poor. His speech left many suspicious of his real motives. Besides the support of many in the Senate – Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus among them – he had the backing of provincial farmers and peasants whose farms and homes were destroyed during the civil wars of the 80s BCE.

Although the election was delayed, Catiline eventually lost. With little alternative, the loss forced him to conceive a diabolical plot: assassinate leading officials of the Roman government and burn the city. The resulting chaos would call for him to assume leadership. However, the uncovered plot by Cicero resulted in a trial for five of the conspirators; Catiline was not among the five, for he had already left the city, branded as a public enemy.

On 5 December 63 BCE, a hearing was held before the Senate at the Temple of Concord. The conspirators did not deny their guilt, so the question was not about proving guilt or innocence but punishment. Speaking in a clear and calm manner, Caesar (who had quickly distanced himself from Catiline) addressed the Senate and called for imprisonment: a lifetime in chains. He said one must follow Roman law and tradition – death was something fixed by the gods, not as a punishment but as a natural end. He declared that while he was not sympathetic to the conspirators, the Senate must not act in haste.

After Caesar, Cato stood and with his usual anger and passion argued for execution. They had forfeited their rights, and while Roman tradition called for a trial, this was a state of emergency. Attacking Caesar, he said Caesar's ideas undermined the city. To Cato, the senators' lives were in danger. They had to face the fact the enemy was within the city walls. The conspirators had confessed to plotting murder and arson, so the only possible course of action was a sentence of death. The Senate applauded and voted for execution. They wasted no time. Each of the five conspirators was taken to the Tullianum, an ancient building in the Forum, where they were forced into a small, dingy room and strangled with a noose by an executioner.

The verbal attack on Caesar led to an intense rivalry that would continue until Cato's last breath. Two historians addressed the attitude of Cato toward Caesar. According to Strauss, Cato believed that "Caesar cared only about power and glory and that he would destroy republican liberty in order to advance his own career" (22). Osgood wrote similarly that Cato believed "Caesar was corrupt, constantly scheming for his own gain in public life" (98).

Tribune of the Plebs

In December 63 BCE Cato began serving his year as tribune of the plebs. Uncharacteristically, he was able to secure a passage of a bill providing for grain subsidies. However, his major concern at the time became Pompey, who had recently achieved success in the East against Mithridates VI (120-63 BCE) and some pirates in the ancient Mediterranean and was returning to Rome. Romans, in particular the Senate, were fearful that he would use his army to march on Rome to secure a consulship.

Pompey had requested the elections be delayed, not for himself, but for one of his officers. Of course, as always, Cato objected. In a dispatch, Pompey assured the Senate that his only goal was with good intentions. He wanted land for his veterans, which could be paid for by the money his campaign in the East had brought to the treasury. Cato objected again – he never passed on an opportunity to oppose Pompey. Cato claimed it was a ploy so that he could run for consul. Many senators were prepared to work out a compromise on Pompey's land request, but Cato stood and began to speak; he spoke until sundown. After months of delay, the bill died. Failing in the Senate, Pompey turned to the Plebian Assembly but failed again. He turned to the one person who could help him.

Caesar had been in Spain as part of his praetorship. He was returning to Rome and wanted a consulship and promised to help Pompey. Cato was less concerned about the agrarian bill than the power it might give Caesar and Pompey. Caesar won the consulship and was able to get Pompey's bill through the Tribal Assembly, although Cato had to be threatened with arrest. At the year's end, Caesar went to Gaul, and Cato went to the newly annexed Cyprus.

In Cyprus, he was as tenacious as always, confronting the extravagance of the ruling Ptolemy (brother of Ptolemy XII of Egypt) and auctioning off the spoils of luxury – goblets, furniture, jewels, and purpose robes. The thought of losing his kingdom drove the young Ptolemy to commit suicide. When the treasure chests were unloaded in Rome and taken to the treasury, people were in awe. Plutarch wrote. "…when the money was carried through the streets, the people much wondered at the vast quantity of it, and the senate being assembled, decreed him in honorable terms an extraordinary praetorship" (858). Cato declined the honors.

Triumvirate & Civil War

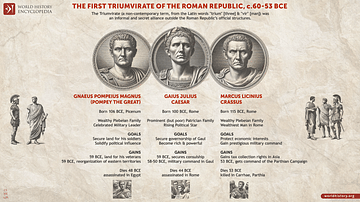

The discord that had risen between Cato and Caesar (Pompey as well) led to the formation of a First Triumvirate by Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus. However, over time, the alliance would begin to weaken. After a meeting in 56 BCE, the alliance was temporarily renewed, with Caesar's command in Gaul extended, while Pompey and Crassus would become consuls. But the death of Pompey's wife – Caesar's daughter – caused a ripple between Caesar and Pompey. The death of Crassus in Parthia at the Battle of Carrhae, 53 BCE, caused further alienation. Two camps emerged: one siding with Caesar and the other with Pompey. It was the prelude to a civil war. David Gwynn called the split "a struggle for power, gloria and dignitas, the selfish principles of the Roman elite" (111).

Caesar's time in Gaul was coming to an end. Osgood maintained that for years Cato had been demanding Caesar be stripped of his command, but now it was too late. Opposing the Senate's wishes, Caesar refused to relinquish his command of eight legions in Gaul and one at Ravenna, 5,000 infantry and 300 cavalry in total. The Senate became nervous, realizing that Caesar's men were loyal to him, not to Rome. Pompey, who had two legions in Rome and seven in Spain, recognized that it had become too risky to defend Rome and, seeing the threat Caesar posed, allied himself with Cato. The only alternative was to evacuate the city. Cato said the one choice the Senate had was to give Pompey supreme command. When Caesar learned that Pompey had "accepted the sword," he sent orders for more of his army to cross the Alps. Osgood wrote that "Caesar was not going to let himself be intimidated" (208). A compromise could not be worked out, and it was apparent that "the Senate had declared war on Caesar" (209). On 11 January 49 BCE, Caesar and one legion crossed the Rubicon. Plutarch wrote that "Pompey finding he had not sufficient forces and that those he could raise were not resolute fortook the city" (875)

Pharsalus

The Battle of Pharsalus was the climax to months of cat and mouse. With Caesar crossing the Rubicon, Pompey fled to Brundisium; Caesar followed, but Pompey fled again. Caesar turned his attention to Spain to face the Roman forces there. After being victorious, he returned to Rome where the Senate named him dictator. Leaving the city, Caesar sailed to meet Pompey at Dyrrachium where Pompey was building an army. Caesar (with reinforcements from Mark Antony) laid siege, but Pompey sailed out of the city and drove Caesar back. Pompey left, following Caesar. Finally, they met on the plains of Pharsalus in central Greece and engaged in battle – Pompey with eleven legions against eight of Caesar.

On 9 August 48 BCE, outnumbered, Caesar was victorious. He left Pharsalus and returned to Rome. Pompey escaped to Egypt where he was murdered by Ptolemy XIII: something that angered Caesar. With only one legion, Cato had remained in Dyrrachium, assigned to safeguard the supplies and arms. Hearing of Pompey's loss, he left Dyrrachium and sailed to Africa, finally arriving at Utica. After he reached Utica, Cato reinforced the city walls and built new towers. He stockpiled weapons and arms, making the city impregnable. Osgood wrote that "Cato would no sooner surrender to Caesar than the sky fall" (233). By this time Caesar had left Rome, traveled to Sicily, and then Egypt. Leaving Egypt, he engaged Mithridates' son in battle and returned to Rome. In December 47 BCE, he sailed to Sicily and then to Africa, where he later routed the armies of Metellus Scipio and King Juba I of Numidia. On 8 August 46 BCE, Cato learned of the routing and made preparations for the city's evacuation.

Suicide

Cato finally realized that any chance of confronting Caesar would be futile. Returning home, he bathed and ate dinner. Over wine, he discussed Stoicism with a few friends. Relaxing in his bedroom, he read Plato's Phaedo where Socrates was contemplating his own suicide. Stories vary on what happened next, but most agree on the basics. He discussed business, rested, and when he woke found that his sword was missing. Demanding its return, he stabbed himself, but missed his heart, exposing his bowels. His son and doctor entered his room and tried to put the intestines back in, but Cato pushed them away, tore at the exposed intestines, and died.

Plutarch described the scene best:

... he again fell into a little slumber. At length Butas [his servant] came back and told him that all was quiet at the port. Thus, Cato laying himself down as if he would sleep out the rest of the night ... took his sword and stabbed it into his breast ... he did not immediately die of the wound but struggling, fell off the bed ... immediately his son and all his friends came into the chamber ... but Cato ... thrust away the physician ... plucked out his own bowels, and tearing open the wound immediately expired. (875)

Cato did not want to surrender nor did he want to be pardoned. Anthony Everitt in his book Nero wrote of suicide that "one of the curiosities of Roman elite life was a propensity to kill himself when he faced adverse circumstances" (41). Suicide was seen as respectable. According to Osgood, Cato wanted to show that no tyranny, however mild, was unacceptable for one who prized freedom.