This text is part of an article series on the Delian League.

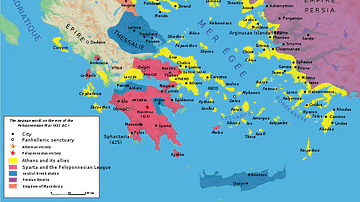

The fifth phase of the Delian League begins with the Peace of Nicias – a settlement that settled nothing – and ends with the start of the Decelean War (also referred to as the Ionian War). This conflict's beginning overlaps the League's disaster in Sicily, which occurred shortly thereafter (421/0 – 413/2 BCE). Although the resources still available to the Delian League at the end of the Ten Years War show the Athenians could have continued fighting, the recurring rebellions among allies coupled with the failures in Megara and Boeotia dimmed any promise that had followed the Athenian victory at Pylos.

The siege of Poteidaia and the defeat at Delium alone illustrated the high cost the Delian League suffered waging an aggressive war. The annual destruction of Athenian crops, the plague, and ten years of fighting had strained temperaments within the Delian League and wasted a treasury long in accumulation.

THE PEACE OF NICIAS

The Peace of Nicias promised peace between the two Leagues for 50 years but delivered only eight. Though it provided free access to common shrines, Delphic independence, and rules for arbitration, the Delian League still lost Amphipolis through Sparta's failure to enforce the agreement. The Athenians also refused to surrender Pylos and Nisaea, the latter of which threatened Megara. The Peloponnesian League nevertheless abandoned Torone, Scione, and various other poleis, while the Delian League retained Poteidaia, Corcyra, Sollim, Argilus, Stagirus, Acanthus, Stolus, Olynthus, Spartolus, and Anactorium. This result angered both the Corinthians and Megarans.

Athens thus realized revenue of about 1,200 talents from the assessment of 420 BCE. Their grip on the Confederacy of Delos remained intact. Corinth, Megara, Elis, and Boeotia, in fact, voted against the final terms of the negotiated settlement. Argos also indicated it would not renew its own treaty with Sparta. The Spartans elected not to press these issues and instead chose to establish an independent 50-year epimachia with Athens, which the Athenians accepted, and this permitted the two sides to work around the deficiencies of the actual Peace Treaty. As a gesture of goodwill, the Athenians returned the men captured at Sphacteria.

Although many of the allies in both Leagues remained dissatisfied, the two hegemons imposed the terms on each. This only exasperated the underlying discontent among their various members, especially in the Delian League – shown, for example, by reliefs, which now depicted tribute as seized money bags.

SHIFTING ALLIANCES & NEW LEAGUES

The unsatisfied Corinthians immediately sought to establish a fourth league in the Hellenes. They secretly approached Argos. The Argives had a long-standing quarrel with Sparta, and they readily agreed with almost no alterations to Corinth's proposal. Mantinea soon joined this new alliance followed shortly thereafter by Elis (420 BCE). When Sparta learned of these maneuvers, they complained bitterly to Corinth and then intervened directly, which delayed further negotiations. Although Corinth made subsequent appeals to Megara, Tegea, and Boeotia, those attempts failed, and Corinth's resolve to form this new League faltered.

Sparta, however, felt threatened by the resulting Triple Alliance between Argos, Elis, and Mantinea. They openly attacked Mantinea, which brought Argos to their defense. The Argives proved no match for the Spartan Army. The Spartans then turned against Elis. After a series of engagements, the Spartans assembled an effective northern defense boundary. Meanwhile, further negotiations commenced between Athens and Sparta, and Athens agreed to surrender Pylos and move the population to Cephallenia but only if Boeotia surrendered Panactum. The Athenians further permitted the Delians to return to their island at the behest of the Delphic oracle.

The newly elected Ephors in Sparta, however, once again shifted Spartan policy, and they desired instead to renew the war with Athens. The Spartans approached Boeotia and Corinth to coax Argos into yet another separate alliance. Argos, however, turned to Boeotia with its own designs: Argos, Boeotia, Corinth, Megara, and Thrace would form an alliance of their own, but Boeotia did not trust Corinth. The scheme failed, and Boeotia instead approached Sparta with a separate alliance, who accepted.

The Boeotians dismantled Panactum, which angered the Athenians, and thus they refused to surrender Pylos. Nevertheless, fearing the possibility of alliances between Boeotia, Sparta, and Athens, the Argives sought an independent alliance with Sparta. All of these rapidly evolving and shifting allegiances in the Peloponnese and Boeotia caught the attention of the young, flamboyant, and highly ambitious Athenian Alcibiades, son of Cleinias.

THE QUADRUPLE ALLIANCE

Alcibiades recognized that the Triple Alliance of Elis, Mantinea, and Argos had in short order seriously threatened the relative stability of the Peloponnese. Entering into it, furthermore, offered minimal risk to Athens directly. He argued further that, if the Spartans addressed their problems with Argos, then they would simply renew their aggressions against an isolated Athens. Alcibiades sent word to the Argives privately urging them to come with representatives from Elis and Mantinea. The invitation arrived before Argos had negotiated with Sparta, and the Argives received it enthusiastically. Although Sparta attempted to quash the negotiations, the Athenians entered into a hundred-year alliance with Argos, Elis, and Mantinea, and, with it, the Athenians had successfully divided the Peloponnese (420 BCE).

Corinth, faced with the Delian League to the north, and this new Quadruple Alliance to the south, subsequently abandoned any ties with Elis and Mantinea and aligned with Sparta. The Eleans, in turn, banned Sparta from the temples, sacrifices, and competitions of the Olympic Games. The Spartan colony of Heraclea came under attack, and they asked for assistance from the Thebans, who took control of the polis – fearing the Spartans could no longer defend it (419 BCE). The Athenians, moreover, marched a small armed force through the Peloponnese and negotiated an alliance with Patrae, but the Corinthians and Sicyonians prevented the Athenians from building a fort at Rhium (across from Naupactus). Argos then attacked Epidaurus. The Athenians asked for a conference at Mantinea to discuss peace, but the Corinthians refused. When a Spartan army approached the Epidaurian border, the Argives and Athenians withdrew.

THE BATTLE OF MANTINEA

The following summer (418 BCE), the Spartans finally responded against the new alliances with vigor. King Agis led 8,000 Spartan, Tegean, and other Arcadian hoplites against Argos, and they ordered the Peloponnesian League to assemble forces at Phlius: 12,000 hoplites as well as 5,000 Boeotian light-armed troops with 1,000 cavalry. The Argives fielded 7,000 hoplites, the Eleans 3,000, and the Mantineans 2,000. The Athenians, whose enthusiasm had waned, sent only 1,000 hoplites and 300 cavalry, but they would arrive too late.

When King Agis reached Phlius, the Peloponnesian army numbered 20,000 men, "the finest Greek army assembled up to that time" (Thuc. 5.60.3). The two sides negotiated a four-month truce and withdrew. The Mantineans used the respite to besiege and take Orchomenus. Shortly thereafter, factions arose in Tegea, and they entertained joining the Quadruple Alliance. The Spartans responded swiftly. Alcibiades' expansionistic plan and the short-lived Quadruple Alliance ended with the decisive Spartan victory at the Battle of Mantinea (418 BCE).

ARGOS & THRACE

The Athenians withdrew from Epidaurus while the Argives withdrew from the Quadruple Alliance and allied with Sparta. Soon, however, civil war broke out in Argos (417 BCE), and the new regime once again sought an alliance with Athens, who remained ambivalent. For the next three years, Argos and Sparta would engage in a series of raids and counter-raids.

While the Athenians had become involved in the Peloponnese, some of the Chalcidean poleis had rebelled from the Delian League again, and the Athenians planned an expedition to recover them, but, when Perdiccas refused to help, the Athenians simply ordered a blockade of the Macedonian coast.

DESTRUCTION OF MELOS

Athenian temperament and attentions changed with the sudden decision to coerce Melos into the Delian League (416 BCE). Though listed in the assessment of 425 BCE, Athens had failed to exact tribute. The precise circumstances of this move remain unclear, and the sources do not indicate any immediate grievance, but the Athenians apparently decided the Melians had benefited from the Delian League while bearing none of the burdens long enough.

Athens abruptly sent 30 triremes with 1,200 hoplites and called for an additional eight allied triremes with 1,500 hoplites. The Delian League force converged on the island. They made camp, laid waste to the fields, and sent ambassadors to persuade surrender without battle or siege, but the Melian magistrates refused to permit the embassy to address the populace.

Thucydides' account of the ensuing discussion, presented as a unique dramatic dialogue, has prompted repeated scholarly debate. The Athenians presented a "cruelly blunt" argument: the reality of the disparity between Athens and Melos rendered all discussion of justice and injustice moot, only equality ever prevented one side from imposing its will on the other (Thuc. 5.89). The Melians, however, remained convinced their cause proved just, the gods would protect them, and the Spartans would come to their aid. Fortune, the Melians held, would bring them victory. The Athenians countered that the Spartans acted only when confident of their superiority. They would therefore not cross the Aegean as long as Athens controlled the sea.

When Melos finally surrendered after a long siege, the Athenians executed the men and enslaved the women and children. Athens offered the same justification for their actions that they had presented to Sparta at the start of the Ten Years War:

We have done nothing amazing or contrary to human nature if we accepted a rule given to us and then did not surrender it, since the strongest motives conquered us – honor, fear, and self-interest. We are not the first to have acted this way, for it has always been ordained that the weaker are kept down by the stronger. (Thuc. 1.76.2)

During this time, Nicias personally led a grand procession and dedication of Apollo's Temple on Delos. The destruction of Melos and the opulent display on Delos showed the Hellenes that the Delian League had not withered under war.

SEGESTA & LEONTINI

That winter, Athens received an unexpected appeal from Segesta and Leontini in Sicily to aid them in their war against Selinus and Syracuse (416/5 BCE). Athenian envoys returned that spring with 60 talents and the promise of more money (415 BCE). The Segestan invitation emphasized traditional ties, allied obligation, and defense. Athenian attention, again led by the wildly expansionist and ambitious Alcibiades, turned solidly west. He argued that the Athenians could conquer not only Sicily but also Carthage. The Athenians soon "longed for the rule of the whole island" (Thuc. 6.6.1), an undertaking demanded by a populace hungry for power and greedy for grain but, according to Nicias, totally ignorant of the scope.

The Athenians initially considered to send a relatively modest force of 60 triremes without hoplites under the command of single general but instead chose three. The goals nonetheless remained limited: aid Segesta, resettle Leontini, and "settle affairs in Sicily in whatever way they judged best" (Thuc. 6.8.2). Four days later, however, the Ekklesia met to consider equipping the fleet. When Nicias attempted to cow the crowd with the magnitude and folly of the endeavor against Syracuse, his effort backfired spectacularly.

Alcibiades countered matter-of-factly: the Athenians must aid their allies. "That is how we acquired our rule and that is how others who have ruled acquired theirs—by always coming eagerly to the aid of those who called upon us, whether Hellene or barbarian" (Thuc. 6.18.2). Athenians allies were, in fact, the first line of defense for the Delian League. Alcibiades' Sicilian strategy, like that he pursued with the Quadruple Alliance in the Peloponnese, relied on surprise, psychological impact, and diplomacy. Nicias argued that the forces allocated could not accomplish the goal. In response, the Ekklesia, convinced Sicily could greatly increase their wealth, voted overwhelmingly to equip the fleet with everything necessary to bring those poleis into the Confederacy.

THE GREAT SICILIAN EXPEDITION

The Sicilian Expedition proved the most ambitious attempt to expand the Delian League to date. It consisted of 134 ships (60 Athenian, 30 Chian, and 10 Methymna triremes; 2 Rhodian penteconters; 40 Athenian troop carriers and various vessels from Chios and other League members); 5,100 hoplites (1,500 Athenian, 500 Argive, and 2,150 drawn from Euboea, Andros, Naxos, Samos, and Miletus with 250 Mantinean mercenaries); along with 900 light-armed troops and 30 cavalry; together with stone masons and carpenters drawn from all over the Aegean – "the most expensive and glorious armament coming from a single polis with a purely Hellenic force that had put to sea up to that time" (Thuc. 6.31.1).![Greek Trireme [Artist's Impression]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/4650.jpg?v=1710090064)

Almost immediately, setbacks and disappointments plagued the endeavor. The early removal of Alcibiades from command soon led to serious indecision by the remaining military commanders Nicias and Lamachus (415 BCE). Alcibiades fled to Sparta, and the Sicilian Expedition began to falter, eventually preparing for a siege of the polis Syracuse. Athens dispatched 300 Segestan and 100 various allied cavalry reinforcements (414 BCE), quickly followed by ten more ships to assist against Syracuse. By this time, however, the Spartans and Corinthians too had already become involved in Sicily. What began as a grand scheme to absorb Sicily, then Carthage, and from there the whole of the Peloponnese itself, soon deteriorated into a prolonged siege of a single polis.

ARGOS

Athens also elected to enter Argos' war against Sparta after an Argive victory at Thyrea. The Athenians sent 30 triremes, which ravaged the Laconian coast. This act openly violated the Peace of Nicias. Sparta thus made renewed preparations to invade Attica.

The contrast between the mature piety of Nicias and the youthful dash of Alcibiades perhaps offers the best illustration of the misfortune, which came to dominate Athenian policies and, with it, their rule of the Delian League. The death of Pericles brought forth successors like Cleon, Nicias, and Alcibiades, who would act out of personal ambition, but "being more or less equal to one another in political power, and yet each man striving to become first, they turned to pleasing the masses and even handed over management of public affairs to them" (Thuc. 2.65.10).

Neither Nicias nor Alcibiades enjoyed the advantages that had produced Cimon or Pericles. Each succeeded only to interfere with the plans of the other. What happened with the decisions to attack Sicily and aid Argos brought this failing out into the open and would thus threaten the survival of the Delian League.

This article is part of a series on the Delian League:

- The Delian League, Part 1: Origins Down to the Battle of Eurymedon (480/79-465/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 2: From Eurymedon to the Thirty Years Peace (465/4-445/4 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 3: From the Thirty Years Peace to the Start of the Ten Years War (445/4–431/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 4: The Ten Years War (431/0-421/0 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 5: The Peace of Nicias, Quadruple Alliance, and Sicilian Expedition (421/0-413/2 BCE)

- The Delian League, Part 6: The Decelean War and the Fall of Athens (413/2-404/3 BCE)