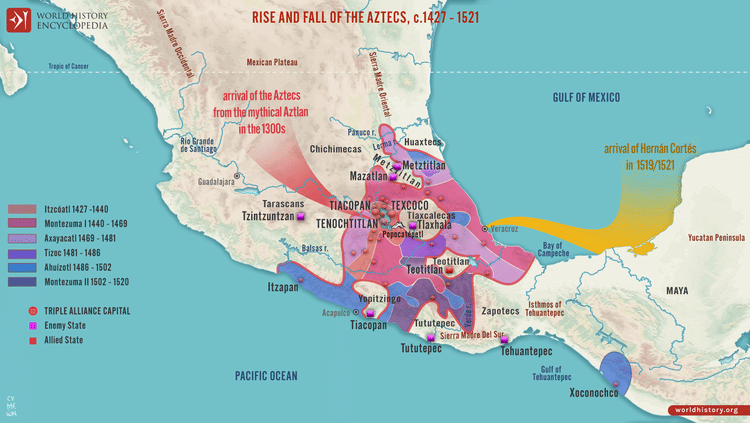

The Aztec empire flourished between c. 1345 and 1521 CE and dominated ancient Mesoamerica. This young and warlike nation was highly successful in spreading its reach and gaining fabulous wealth, but then all too quickly came the strange visitors from another world. Led by Hernán Cortés, the Spaniard's formidable firearms and thirst for treasure would bring devastating destruction and disease. The Conquistadores immediately found willing local allies only too eager to help topple the brutal Aztec regime and free themselves from the burden of tribute and the necessity of feeding the insatiable Aztec appetite for sacrificial victims, and so within three years fell the largest ever empire in North and Central America.

The Aztec Empire

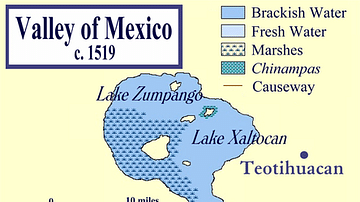

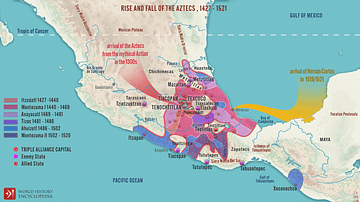

By around 1400 CE several small empires had formed in the Valley of Mexico and dominant amongst these were Texcoco, capital of the Acholhua region, and Azcapotzalco, capital of the Tepenec. These two empires came face to face in 1428 CE with the Tepanec War. The Azcapotzalco forces were defeated by an alliance of Texcoco, Tenochtitlan (the capital of the Mexica) and several other smaller cities. Following victory, a Triple Alliance was formed between Texcoco, Tenochtitlan, and a rebel Tepanec city, Tlacopan. A campaign of territorial expansion began, where the spoils of war - usually in the form of tributes from the conquered - were shared between these three great cities. Over time Tenochtitlan came to dominate the Alliance, its leader became the supreme ruler - the huey tlatoque ('high king') - and the city established itself as the capital of the Aztec Empire.

The empire continued to expand from 1430 CE, and the Aztec military - bolstered by conscription of all adult males, men supplied from allied and conquered states, and such elite groups as the Eagle and Jaguar warriors - swept aside their rivals. Battles were concentrated in or around major cities, and when these fell, the victors claimed the whole surrounding territory. Regular tributes were extracted, and captives were taken back to Tenochtitlan for ritual sacrifice. In this way, the Aztec empire came to cover most of northern Mexico, an area of some 135,000 square kilometres with a population of around 11 million. As the chronicler Diego Duran put it, the Aztecs were "Masters of the world, their empire so wide and abundant that they had conquered all the nations." (Nichols, 451)

The empire was loosely kept together through the appointment of officials from the Aztec heartland, inter-marriages, gift-giving, invitations to important ceremonies, the building of monuments and artworks which promoted Aztec imperial ideology, imposition of the Aztec religion (especially worship of Huitzilopochtli), and most importantly of all, the ever-present threat of military intervention. This meant that it was not a homogenous and mature empire where its members had a mutual interest in its preservation. Some states were integrated more than others whilst those on the extremities of the empire were exploited merely as buffer zones against more hostile neighbours. In addition, the Aztecs were heavily defeated by the Tlaxcala and Huexotzingo in 1515 CE. One neighbouring power in particular, a constant thorn in the Aztec flank, was the Tarascan civilization. Endlessly troublesome, they, the Tlaxcalans and others, would prove to be vital allies for the Spaniards when they came to plunder and conquer the vast riches of Mesoamerica. Fighting for their independence from Aztec rule they did not realise that they would merely be replacing one rapacious overlord for another even more destructive one.

By 1515 CE rumours in the Aztec heartlands and several bad omens of a rapidly approaching crisis were fuelled by sightings off the coast of fantastic floating temples. The visitors from the Old World had finally come.

Hernán Cortés & the Conquistadores

The Spanish Governor of Cuba, Diego Velasquez, had already sent several expeditions to explore the mainland coast of America starting in 1517 CE, and these had reported strange ancient stone monuments and brightly dressed natives from whom were bartered fine gold objects. Ironically, one group of natives had actually been sent by the Aztec king Motecuhzoma II Xocoyotzin (Montezuma) to see for themselves who these mysterious bearded men were, but a lack of a common language meant the Spanish returned to Cuba unaware they had missed an opportunity to finally prove there was a large civilization and source of treasure beyond the coast. Velasquez was convinced enough by the gold objects, though. The governor organised another expedition and chose as its leader Hernán Cortés. In his fleet of 11 ships went 500 soldiers and 100 sailors, all of them adventurers and treasure-seekers.

Cortés, a native of Extremadura, had studied law at university, but at 19 years old he had decided to leave Spain and try his luck in the Caribbean colonies. After running a plantation and participating in the conquest of Cuba, he was now in his mid-30s and ready for his stab at fame and glory. Perhaps not only out for gold, Cortés was a deeply religious man, and the spirit of evangelism, for him if not his followers, was an extra motivation to open up this New World.

Landing on the Tabasco coast at Potonchan, Cortés immediately met hostilities, but the Europeans easily subdued the natives with their superior weapons and tactics. As a gift of reconciliation Cortés was presented with some slave girls, and one of these, a certain Malintzin (aka Marina or Malinche), would prove an invaluable asset as she spoke both the local Mayan language and, crucially, also the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs. One of Cortés' men spoke the former so that now the way was open to parley with any representatives the invaders came across. Malintzin would remain at Cortés' side throughout the campaign, and together they would have a son, Don Martin.

Cortés was directed to sail north, and this he did, landing near the town of Cempoala where he came across two Aztec tax collectors extracting the king's tribute from the locals. Word soon reached Motecuhzoma that a large force of violent men was confidently approaching the Aztec heartlands.

Facing the Enemy - Montezuma

Motecuhzoma, after consulting his council of elders, decided on a strategy of diplomacy. He sent gifts to the Spanish, which included ceremonial costumes, a massive gold disk representing the sun, and an even bigger silver one representing the moon. These were gratefully received and likely made the Spanish even more interested in plundering the land for all it was worth. Ignoring instructions to return to Cuba, Cortés instead sent a shipload of the treasures they had so far acquired and letters requesting royal support to Charles V of Spain. Then a garrison was established at Veracruz on the coast. Cortés next burned all of his ships to remind his men that in the following months of hardship it was to be conquest or death. In August 1519 CE, Cortés marched directly to Tenochtitlan.

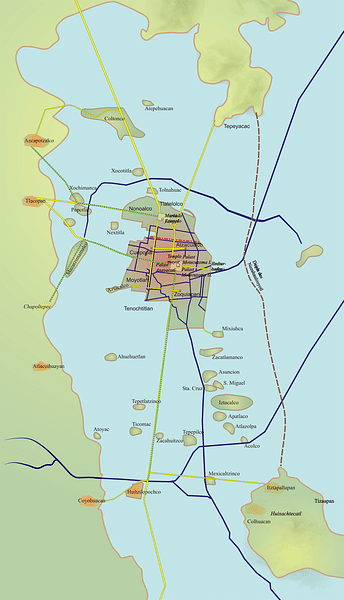

The capital was located on the western shore of Lake Texcoco and boasted at least 200,000 inhabitants making it the largest city in the Pre-Columbian Americas. It was a huge trading centre with goods flowing in and out, such as gold, turquoise, foodstuffs, and slaves. The Spanish invaders, allowed to freely enter the city, were hugely impressed by its splendour, its magnificent architecture and artwork, its wonderful gardens, artificial lakes, and flowers. Cortés was eager to meet the Aztec king Motecuhzoma. Taking the position of tlatoani, meaning 'speaker' in 1502 CE, he ruled as an absolute monarch and was considered a god by his people and a manifestation and perpetuator of the sun. Initially, relations were friendly and valuable gifts were exchanged between the two leaders. Cortés received a necklace of golden crabs, and Motecuhzoma a necklace of Venetian glass strung on gold thread and scented with musk.

The history of the conflict about to unfold is much debated amongst scholars, and it is unlikely that the Spanish chroniclers presented a completely impartial account of events. It has been noted that it does seem strange that such a powerful ruler as Motecuhzoma should cut such a passive figure in the record of events brought down to us. However, against that it is certainly true that the Spanish had already shown their military prowess and the devastating effectiveness of their superior weaponry - cannons, firearms and crossbows - in quickly defeating a force of Otomi-Tlaxcalan, and they had also taken quick and ruthless reprisals against a treacherous plot by the Cholollan. Perhaps Motecuhzoma had taken note of this and took the more prudent policy of appeasement rather than engage the enemy in the field, at least as an opening strategy. This seems a more reasonable explanation than the traditional view, now rejected by modern historians as a post-conquest rationalising fiction, that Motecuhzoma reverently believed that Cortés was the returning god Quetzalcoatl of Aztec mythology.

Whatever the reasons, the initial air of cordiality between the two sides soon turned sour for within two weeks the Aztec ruler was audaciously taken hostage and placed under house arrest by the small Spanish force. Motecuhzoma was forced to declare himself a subject of Charles V, handover more treasure and even allow the placing of a crucifix on top of the Great Pyramid or Templo Mayor in the city's sacred precinct.

The Fall of Tenochtitlan

The crisis deepened when Cortés was forced to return to Veracruz and face a new force sent from Cuba to arrest him for disobeying his orders to return to Cuba. Some of the remaining Spanish, commanded by Pedro de Alvarado, were then killed at Tenochtitlan after they tried to interrupt a ceremony of human sacrifice. This incident was just what Cortés needed, and after battling the Cuban relief force at Veracruz and persuading its leader Panfilo Narvaez to join his cause, he returned to the city to relieve the besieged remaining Spanish. The Aztec warrior commanders, unhappy at Motecuhzoma's passivity, overthrew him and set Cuitlahuac as the new tlatoani. The Spanish tried to have Motecuhzoma calm the populace, but he was struck in the head by a thrown rock and killed. Some think the Spanish strangled him in secret as he was clearly of no use to either side any longer.

Holed up in the royal palace, Cortés resisted several waves of attacks and then fought to control the gigantic Templo Mayor pyramid, which was being used as a handy vantage point to rain down missiles on the Spanish. A fierce battle ended in Cortés taking control of the temple, which he then set fire to, horrifying the population. Cortés grabbed what booty he could and fled the city in a running night battle on the 30th of June, 1520 CE, in what became known as the Noche Triste (Sad Night).

Gathering local allies from his Tlaxcala base, and now supported by Texcoco, Cortés first won a great battle near Otumba and then returned to Tenochtitlan ten months later, laying siege to the city with a fleet of specially built warships. With these ships, Cortés was able to block the three main causeways which linked the city to the edge of Lake Texcoco. Lacking food and ravaged by smallpox disease earlier introduced by one of the Spaniards, the Aztecs, now led by Cuauhtemoc, finally collapsed after 93 days of resistance on the fateful day of 13th of August, 1521 CE. Tenochtitlan was sacked and its monuments destroyed. The Tlaxcalans were ruthless in their revenge and slaughtered men, women, and children wholesale, even shocking the hardened Spanish veterans with their atrocities. From the ashes of this disaster rose the new capital of the colony of New Spain, and Cortés was made its first governor in May 1523 CE.

Conquering the Empire

With the fall of Tenochtitlan, the Spanish set about pacifying the rest of the empire and discovering what other treasures could be plundered. In this, they were helped enormously by two factors. The first was help from disgruntled subject peoples or traditional enemies of the Aztecs. On the march to Tenochtitlan, Cortés had already enlisted the enthusiastic help of the Tlaxcalans, both in men and supplies. With the collapse of the Aztec hierarchy, other local communities were only too willing to see the back of them and free themselves from heavy tribute and the systematic capture of people to be sacrificed at the Aztec capital.

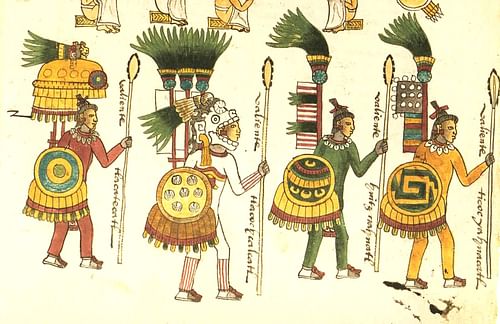

The second factor in the Spaniard's favour was the primitive weaponry and ritualised warfare of their opponents. Aztec warriors wore padded cotton armour, carried a wooden or reed shield covered in hide, and wielded weapons such as a super sharp obsidian sword-club (macuahuitl), a spear or dart thrower (atlatl), and bow and arrows. Effective though these were against even more poorly equipped native Americans, they were next to useless against the Spanish guns, crossbows, steel swords, long pikes, cannons, and armour.

Cavalry was another devastating weapon in the hands of the Europeans. Elite Aztec warriors and officers also wore spectacular feathered and animal skin costumes and headdresses to signify their rank. This made them highly conspicuous in battle and a prime target to dispatch as early as possible. Shorn of their commanders, the Aztec units often disintegrated into panic. The Aztecs were used to loose formations in battle; their primary objective had always been to capture a valiant opponent alive so that they might be later ritually sacrificed, and warfare was highly ritualised with precise moments for starting and ending. The objective of Aztec warfare was never to destroy completely the enemy and overturn their culture, while the Spanish were intent on exactly that. The two sides were not just centuries but millennia apart in terms of arms technology and warfare tactics.

There could only be one winner, and within three years Mesoamerica, including the Tarascan capital of Tzintzuntzan and the Maya highlands, were under Spanish control. Gradually, Franciscan friars arrived to spread Christianity, and the bureaucrats took over from the adventurers. In 1535 CE, Don Antonio de Mendoza was made the first viceroy of the kingdom of New Spain.

Conclusion

Montezuma seems to have had some instinct that troubled times were ahead as he gave great importance to omens such as a comet sighted in 1509 CE, and he constantly consulted soothsayers for advice. Aztec mythology foretold that the present era of the 5th sun would eventually fall just as the previous four eras had done, and so it came to pass. The Aztec empire collapsed, its temples were defaced or destroyed, and its fine art melted down into coins. Ordinary people suffered from the European-introduced diseases which wiped out up to 50% of the population, and their new overlords did not turn out to be any better than the Aztecs. Systematically and ruthlessly, the culture of the ancient Mesoamericans, a heritage going back millennia, was repressed and where possible eradicated in an effort to install the new order of the Old World. Unfortunately, with the continued extraction of tribute both in goods and forced labour, this new order was no less brutal and unforgiving than the old one.