No military commander in history has ever won a battle by himself. To be successful he needs the support of a well-trained army who will follow him regardless of the cost whether it be a stunning victory or hopeless defeat. One need only read of Leonidas as he bravely led his 300 Spartans to inevitable defeat at Thermopylae. History has had its share of skilled leaders - Julius Caesar, Hannibal, and later Napoleon. However, all three of these men must pay homage to a single individual and his army. Alexander the Great conquered most of the known world of his time. From his father King Philip of Macedonia he inherited a versatile, well-trained army unlike anything that had ever existed. United in a single purpose, they fought as one. Alexander recognized this and is quoted as saying, “Remember upon the conduct of each depends the fate of all.”

Although he owes much of his success to his father's foresight, the young king's achievements in battle can be traced back to the origin of the hoplite phalanx of early Greece. Around 700 BCE the cities of Corinth, Sparta, and Argos created a close-ordered battle formation that became known as the phalanx. The reason for this development was due in part to a changing Greece. Greece was emerging from a dark period in its history - the troubling times of the poet Homer. There was the emergence of the polis or city-state and the expansion of colonies founded as near as Ionia and as far away as Sicily. With trade and the Greek world expanding, for political and economic reasons, each city had to learn to defend itself.

Earlier Greek Warfare

Two powerful city-states rose to dominate Greece. While Athens would become a naval power, Sparta easily emerged as the atypical military city, initiating a strict code of conduct with intense military training for every male citizen. It was the birth of the citizen-warrior. Every citizen was required to defend the city in the event of war. Although a Spartan boy learned enough to be literate, more importantly, he learned how to endure pain and to conquer in battle, in essence to fight as a unit not as an individual. The city itself was like an armed camp. This intense training became evident when Greece was invaded by the Persians under the command of Darius I and later his son Xerxes.

The new soldier was a hoplite, named for the hoplon, his shield. For additional protection he wore a helmet (most often the Corinthian style), covering most of his face except for a t-shaped opening that exposed his eyes, nose and mouth (unfortunately, it did not allow for peripheral vision); Philip would replace this with a Phrygian helmet that allowed for better hearing and visibility. The hoplite wore greaves to cover his calves, a molded cuirass that shielded his torso as well as a long, pleated tunic that protected his abdomen and groin. For a weapon he carried a thrusting spear of five to eight feet in length. The army marched in a close-ordered formation or phalanx where each hoplite carried his shield in a manner that protected his left side and his neighbor's right. This new style of fighting was primarily offensive, advancing in a line into the center of the opposing enemy.

A Disciplined & Organized Army

When Philip II became king of Macedonia in 359 BCE, he inherited an army that was relatively ineffective. He immediately initiated a series of military reforms. Together, Alexander and his father would create an army unlike anything the ancient world had even seen. Previous wars such as the Persian and Peloponnesian War had demonstrated that the old ways were no longer dependable. Philip took a poorly disciplined group of men and turned them into a formidable army. Most historians believed Philip developed his ideas while a hostage in Thebes, observing their notorious Sacred Band. To begin with, he increased the size of the army from 10,000 to 24,000, and enlarged the cavalry from 600 to 3,500; this was no longer an army of citizen-warriors. In addition, he created a corp of engineers to develop siege weaponry such as towers and catapults. Later, Alexander would use these siege towers with devastating effect at Tyre (6,000 would be killed and 30,000 enslaved).

The very nature of the phalanx required constant drilling, and both men demanded strict obedience; punishments would be meted out for those who disobeyed. Like Alexander after him, Philip required an oath of swearing allegiance to the king. They provided uniforms - a simple idea that gave each man a sense of unity and solidarity. Besides the obvious, there was logic behind what they did; each soldier would no longer be loyal to a particular province or town as now he would be loyal only to the king. The battle-hardened men who fought for Philip and Alexander had to remain dedicated to his king and the glory of Macedonia. This loyalty and restructuring became evident at Philip's victory over Athens and Thebes (with the help of an eighteen year old Alexander) at the Battle of Chaeronea; a battle that demonstrated the power and authority of Macedonia.

Philip completely restructured the army. The first order of business was the reorganization of the phalanx, providing each individual unit with its own commander - thereby allowing for better communication. The fundamental fighting unit became the taxes which usually comprised 1,540 men and commanded by a taxiarch. Every taxis was broken into distinct subdivisions. A taxis was composed of three lochoi (each commanded by a lochagos) or 512 men apiece. 32 dekas (a line of ten men – later sixteen) made up each lochoi. Each man occupied only two cubits of space until actual battle, when he used only one cubit.

Weapons & Tactics

Next, Philip changed the principal weaponry from the hoplite spear to the sarissa - an 18-20 feet pike; it had the advantage of reaching over the much shorter spears of the opposition. Obviously, the length of the sarissa made it difficult to handle, demanding both strength and dexterity. The hoplite now became a pezhetairoi or foot companion. Like his predecessor, he, too, carried a shield or aspis - similar to the hoplon, but due to the size of the sarissa (one had to use both hands); it was carried by a sling over the shoulder. Besides the sarissa, each man possessed a smaller double-edge sword or xiphos for close-in-hand fighting.

There was only one drawback to the phalanx - it worked best on flat, unbroken country; however, despite this disadvantage, Alexander used it with amazing success. In almost every campaign the formation of Alexander's army remained the same; however, due to the nature of the field of battle, some changes were made at Hydaspes where archers led the field against Porus' elephants. The pezhetairoi were in the center; the hypaspists were to their right with the cavalry on either flank. Archers and additional lighter infantry served on outer flanks and in the rear. The pezhetairoi were indoctrinated to maintain ranks in all circumstances, although they were able to break smoothly when necessary; this was evident at Gaugamela against Darius' scythed chariots. In battle, the five front ranks lowered their sarissa parallel to the ground while the rear ranks (usually wearing broad-brimmed a straw hat or kausia instead of helmets) carried theirs upright.

As indicated earlier, to the right of these pezhetairoi were the far more mobile hypaspists also called shield-bearers. Although not as heavily armed - carrying only a shorter spear or javelin - they served a special role in both Philip and Alexander's army. They were recruited for their skill and physique, requiring a special level of training. They were mostly from the peasantry of Macedon and, thereby, had no tribal or regional affiliation meaning they loyal only to the king himself. There were three distinct classes of hypaspists - the “royal” who served as the bodyguards of the king as well as guards at banquets and official events, an elite force known as the argyraspids, and finally the actual hypaspists corp. A special band of veterans within the hypaspists would become known as the Silver Shields.

Cavalry

On both the right and left flanks were the cavalry. The cavalry was the army's main strike force and would make the decisive breakthrough of the enemy lines - this was evident at the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela. There were two divisions of the cavalry - the Companion and the prodromoi - the latter was the more flexible and versatile Balkan cavalry which was used primarily as scouts. The Companion Cavalry was the more important division and was commanded at first by Philotas and later by Cleitus and Hephaestion. They were divided into eight squadrons of 200 men each and each man carried a nine-foot lance but wore little armor. Due to the extreme value of the cavalry - 1,000 horses would die at Gaugamela - a steady supply of extra horses was kept at all times. Of course, the most important of these squadrons was that of Alexander. Alexander and his Royal Companions always fought on the right while Parmenio commanded the Thessalian Cavalry on the left flank. Tactics remained simple - the pezhetairoi would hit the center of the opposing army in an oblique angle while the cavalry would attack and punch holes on the flanks. As with the previously abandoned hoplite phalanx, the new army was designed to attack and remained a purely offensive weapon. While well-trained soldiers are always essential for success, an army needs capable leadership, and besides Alexander, the force that crossed the Hellespont had several capable officers, namely Parmenio, Perdiccas, Coenus, Cleitus, Ptolemy, and Hephaestion.

Alexander ran his army from the royal tent where his war counsel would meet in a large pavilion. The tent also contained a vestibule, an armory and the king's personal apartment. The tent was guarded at all times by a special detachment of hypaspists. Although he would always listen to the suggestions of his command staff, Alexander's decision was final. This was most evident before the battle at Gaugamela when Parmenio and a number of other officers suggested Alexander attack Darius at night which Alexander, of course, flatly refused: “I will not steal a victory.”

Crossing the Hellespont

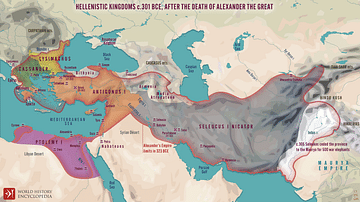

When he entered Asia, the young king brought with him 12,000 phalangists - 9,000 pezhetairoi and 3,000 hypaspists. He also brought with him over 7,000 Greek infantry, most of which would be used to maintain conquered lands as garrison troops. While the army that crossed the Hellespont in 334 BCE was mostly Macedonian, there were others from all over Greece: Agrianians, Triballians, Paeonians, and Illyrians. Since Alexander was also the head of the Legion of Corinth, a number of Greek states provided additional infantry, cavalry and warships. Many of these mercenaries spoke a variety of dialects and came from provinces with a long history of ethnic tension. Luckily, this tension was kept to a minimum. After the defeat of Darius III at Gaugamela in 331 BCE, Alexander realized it was necessary to replace his force's depleted numbers, welcoming new recruits into his army among which were a number of Persians whilst some of his veterans were sent home. All new recruits, whether those arriving from Macedonia or others recruited from local provinces, were trained in the Macedonian style of fighting.

Alexander's Leadership

However, an army - even one that was as well-trained as that from Macedonia - could not have functioned as well without the capable leadership of Alexander. In his book Masters of Command: Alexander, Hannibal and Caesar, author Barry Strauss composed a list of traits necessary for good leadership and among them are judgment, audacity, agility, strategy, and terror. Alexander displayed all of these qualities. Although he would show respect for his enemy, as demonstrated after Issus, he was afraid of no one. He is quoted as saying, “I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a lion.” One of his remarkable abilities was to anticipate the strategy of his opponent, often drawing him onto the terrain of his choosing, once again, this is most visible at Gaugamela. Throughout his conquest of Persia, Alexander didn't necessarily want to bring Darius to his knees; he only wanted to conquer.

Alexander had the respect of his men and never betrayed their trust as he fought next to them, ate with them, and refused to drink water when there wasn't enough for all. Quite simply, he set the example. As was evident at Gaugamela, he was able to rally his men to fight with him. Plutarch in his Life of Alexander the Great wrote,

…he made a very long speech to the Thessalians and the other Greeks and when he saw that they encouraged him with shouts to lead them against the Barbarians, he shifted his lance into his left hand, and with his right appealed to the gods…praying them, if he was really sprung from Zeus, to defend and strengthen the Greeks…and after mutual encouragement and exhortations the cavalry charged at full speed upon the enemy…

In his The Campaigns of Alexander Arrian quoted Alexander as he addressed his troops:

…we of Macedon for generations past have been trained in the hard school of danger and war. [The king compared the two armies - that of Macedon and that of Persia] …and what, finally, of the two men in supreme command? You have Alexander, they Darius.

Before Philip and Alexander, the Persians under Darius I and Xerxes had been repelled by a smaller force - these men of Greece fought unlike anyone and anything the Persians had ever experienced. By the time of Alexander, the fighting force that took him across both Greece and Persia had been perfected. He crossed Asia into India, often fighting a force that outnumbered him. His use of the phalanx and cavalry, combined with an innate sense of command, put his enemy on the defensive, enabling him to never lose a battle. His memory would live on and his determination brought the Hellenic culture to Asia. He built great cities and changed forever the customs of a people.