The pirates of the ancient Mediterranean were not, for the most part, the outsiders who knew no country's allegiance and were the enemies of civilization as they are frequently depicted in novels and other media. They were often employed (or at least encouraged) by one government against the interests of another and were relied upon for slaves by wealthy private citizens and governmental agencies. Governments themselves had no qualms about resorting to piracy during war, and some of the most famous ancient pirates were military or political leaders. Even the famous Cilician pirates could be bought for the right price as is clear from their involvement with Mithridates VI (r. 120-63 BCE) when he employed them against Rome.

In the modern day, pirates are frequently imagined along the lines of Jack Sparrow and the other characters from the popular film franchise Pirates of the Caribbean or the television series Black Sails. These pirates are modeled on the notable figures of the so-called Golden Age of Piracy (1650-1730 CE) and War on Piracy (c. 1716-1726 CE) and, in the case of Black Sails, on the work of the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson (l. 1850-1894 CE) and have little in common with the ancient pirates of the Mediterranean. The ancient pirates were quite often crews providing a service (notably the capture, transport, and sale of people as slaves) for governments or military contingents acting in the interests of their own government although there were pirates who acted independently purely for their own self-interest and profit.

Piracy is first mentioned in the Egyptian records during the reign of the pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) and was still being practiced in the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages (c. 476 -1500 CE). The pirates of the Golden Age of the 17th and 18th centuries CE were nothing new. They were following in what was, by then, an ancient tradition.

The Earliest Pirates

Pirates are mentioned in the Amarna Letters (14th century BCE), a collection of correspondence between various rulers of the Near East and Egyptian pharaohs of the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE). In one letter, the pharaoh Akhenaten writes to the king of Alasiya (in modern-day Cyprus) accusing him of harboring, aiding, and supporting pirates from the Lukka Lands (in modern-day Turkey). The Alasiyan king denied any involvement with the pirates who were attacking Egyptian ports and pointed out that he was just as much a victim of pirate attacks as Akhenaten:

Why does my brother speak in these terms to me? Does not my brother know what is going on? As far as I am concerned, I know nothing of the sort! Indeed, each year the Lukka people seize towns in my own land. (Bryce, 368)

The Lukka were a people from Anatolia who are recorded as being sometimes the ally and sometimes the enemy of the Hittites. They may have been Luwians, one of the original tribes of the region, but this is unclear. Their home region was regularly referred to as “the Lukka Lands” but appear to have had no fixed boundaries as they concentrated their efforts on the sea and are the earliest people in the Mediterranean defined as pirates.

Sea Peoples & Tyrrhenians

The most famous pirates were the Sea Peoples who destroyed whole regions and toppled empires between c. 1276-1178 BCE. They are best known from the inscriptions of the Egyptian pharaohs of the New Kingdom who defeated them: Ramesses II (The Great, r. 1279-1213 BCE), his son and successor Merenptah (r. 1213-1203 BCE), and Ramesses III (r. 1186-1155 BCE).

The Sea Peoples were a coalition of different nations, not a single ethnic group or nationality, and were made up of the Akawasha, Denyen (Danuna), Lukka, Peleset, Dhardana, Shekelesh, Tjeker, Tursha (Teresh), and Weshesh. Only two of these peoples have been identified in the present day, the Lukka and the Peleset (Philistines). The Denyen/Danuna have been associated with the Cilician city of Adana and the Tursha/Teresh with Etruscans and Tyrrhenians but neither of these claims have been universally accepted and no one knows who the Sea Peoples actually were or where they came from.

Ramesses II, Merenptah, and Ramesses III all report the same sort of experience in dealing with them, however. They came from the sea and struck quickly, causing massive destruction, and were defeated with some effort. Egyptian inscriptions famously exaggerate the challenges of the pharaoh in overcoming his enemies but the reports on the Sea Peoples seem to match similar accounts from other nations.

The last king of Ugarit, Ammurapi (r. 1215-1180 BCE), writing to the king of Alasiya, reported the same experience as the Egyptian pharaohs. The destruction of Anatolia and fall of the Hittite Empire is also similar to the Egyptian accounts. Ramesses II notes how the Sea Peoples were conquering the known world and it was only through great effort that he stopped them from taking Egypt. They were finally defeated by Ramesses III in 1178 BCE and, after that, disappear from the historical record.

It is possible, of course, that they never disappeared but are recorded later under different names. The Teresh, as noted, could be the later Tyrrhenians who were so notorious that a 7th-century BCE hymn attributed (wrongly) to Homer relates how they were so brazen they even kidnapped the god Dionysus and were going to sell him as a slave before Dionysus took control of their ship, filled it with vines and beasts, and turned them all into dolphins when they leaped into the sea to escape him. The Tyrrhenians may have been the Teresh or the Etruscans, but their nationality really does not matter as their name became synonymous with piracy from as early as the 7th century BCE.

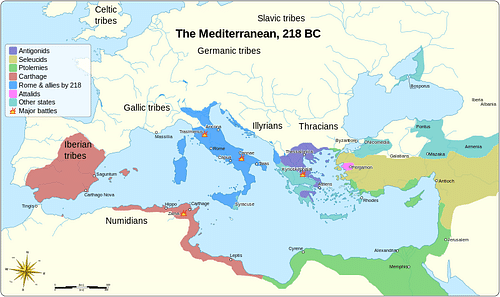

The Illyrians & Queen Teuta

Another people who were regularly identified with piracy were the Illyrians. King Agron (r. 250-231 BCE) of Illyria (on the Balkan Peninsula) pursued an expansionist policy during his reign, focusing especially on a strong navy which could control his coast. Illyria was a kingdom of many different tribes, but Agron's, the Ardiaei, became the most powerful and, under his leadership, they dominated the others. Agron conquered the powerful Aetolians in 231 BCE and was so proud of himself he is said to have consumed too much wine during the celebration afterwards and died within a few days. The throne went to his second wife Teuta (r. 231-227 BCE) who served as regent for his young son Pinnes.

Teuta continued Agron's policies but with a significant difference: she let the fleet loose in the Adriatic Sea as pirates who were free to plunder any non-Illyrian vessels they met. Many of these ships were Roman and the ports of certain islands such as Pharos and Vis were regular stops for Roman merchants. Teuta's pirates were everywhere in the Adriatic, making trade almost impossible as they continued raiding ships and taking cargo, and so Rome finally intervened. They sent two envoys to request Teuta control her pirates, but this request so offended the queen that she had one of them killed and took the other prisoner.

Rome then sent a fleet and an army under Lucius Postumius Albinus (d. 216 BCE) who enlisted the aid of Demetrius of Pharos (r. 222-214 BCE) who had been made governor of Pharos by Agron. He betrayed Teuta and helped Rome to defeat her military in the First Illyrian War (229-228 BCE). Heavy restrictions were then placed on Teuta's reign and navy but, instead of complying, she stepped down. According to legend she then killed herself, but this is uncertain. The Romans then raised Demetrius to power thinking he would be a loyal client king, but as soon as Rome's attention was directed elsewhere, he rebuilt the fleet and released his pirates onto the seas once more. After his defeat and death, Gentius (r. 181-168 BCE) pursued the exact same policy, which resulted in Rome conquering Illyria, ending the reign of the Illyrian pirates.

Cilician Pirates

The Illyrian pirates had followed a code established earlier by Greek pirates of not attacking their own people or region. The Greek pirate Dionysus the Phocaean (5th century BCE) was notorious for seizing any ship he encountered but left Greek vessels alone. The Cilician pirates observed no such policy for the simple reason that they were not all from Cilicia (in modern Turkey, ancient Anatolia). The Cilician pirates were made up of many different nationalities and their only bond was that they used Cilicia as their base of operations. Cilicia's coves and harbors were perfect for concealment, whether in preparation for an attack on a passing vessel or hiding from the authorities, and the region was also timber-rich, which made it an excellent resource for shipbuilding and repair.

The Cilician pirates used many different types of ships but four kinds are mentioned more than others: the hemioliae and myoparones (light, low transport ships) and the bireme and trireme (heavy warships either captured from Rome or, less often, built by pirates). As noted, Anatolia was no stranger to piracy since the time of the Lukka during Akhenaten's reign. The Cilician pirates established a network throughout the region – most likely long in place from the Lukka – for supplies and intermediaries to sell their goods.

They began to gain power as the Seleucid Empire, which controlled part of Cilicia, started to decline after 190 BCE when they were defeated by Rome. Rome allowed Seleucid client kings to continue to rule, but each of these was more concerned with his own power than the region as a whole, and by 140 BCE, civil wars and other unrest made piracy very easy as no one was paying any attention. Further, there was nothing the Seleucid Empire would have done anyway since they, like any other of the time, relied on the pirates for the slaves they needed.

Rome sent an envoy to look into the problem in 140 BCE who reported back that immediate action should be taken against the pirates, but this suggestion was ignored as Rome had other concerns it found more pressing. By 103 BCE, however, the pirates had overstepped their bounds too many times in harassing or capturing Roman vessels and so Marcus Antonius (l. 143-87 BCE, grandfather of Mark Antony) was sent on campaign and conquered the area of Smooth Cilicia (the future Cilicia Campestris). Between 78-74 BCE, the consul Publius Servilius Vatia (served 79 BCE) campaigned in the region and conquered Rough Cilicia (the future Cilicia Aspera), but neither of these did anything to stop or even slow the pirates' activities. In 75 BCE, the Cilician pirates kidnapped a young Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) when he was on his way to study in Rhodes, and in 70 BCE the pirates were paid by the rebel Spartacus (l. c. 111-71 BCE) to transport him and his army to Sicily; they took the money but never showed up as agreed, thus dooming Spartacus' rebellion.

By 67 BCE, Mithridates VI of Pontus was allied with Tigranes the Great of Armenia (r. c. 95 - c. 56 BCE) and was employing the Cilician pirates in his ongoing war with Rome. He was facing the formidable Roman general Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) who made the pirate problem a priority. He divided the Mediterranean into 13 districts, assigning a fleet and commander to each, and when one district was cleared of pirates, that fleet joined efforts in another. By this process, Pompey steadily killed and captured the pirates until he defeated the last of them at the Battle of Coracesium in 67 BCE, just off the coast of Cilicia. Instead of executing the pirates (by beheading or crucifixion), he relocated them to the lowlands of Cilicia Campestris, where they assimilated with the rest of the population and became productive members of society.

Piracy & Rome

After resolving the piracy problem in a mere 89 days, Pompey went on to win his war against Mithridates VI in 63 BCE, but this does not mean the pirates were taken care of for good. Piracy continued as a viable way to make a living because it offered the possibility of upward mobility and far more profit than farming, fishing, or fighting for someone else. The Cilician pirates who had not been relocated – or perhaps even some who had – most likely regrouped before Pompey had even left the region.

In the civil war between Pompey and Caesar (49-45 BCE), piracy was employed by both sides. Pompey's own son, Sextus Pompey (l. 67-35 BCE) was a pirate and commanded his own fleet, seeking revenge on Caesar after his father's assassination in 48 BCE. After Caesar was assassinated in 44 BCE, his nephew Octavian (the future Augustus, r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) and Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE) hunted down the assassins and then, following Antony's involvement with Cleopatra VII of Egypt (l. c. 69-30 BCE), fought with each other. Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra's navy at Actium in 31 BCE and shortly afterwards became the first Roman emperor.

The empire required even more slaves than the Roman Republic had and so the Cilician pirates went right back to work. Rome had no reason to interfere with them now because they were essentially sub-contractors supplying Rome with slaves. The Cilician port of Side (pronounced see-day) became the administrative center for the slave trade in the Mediterranean and generated enormous wealth. Not all pirates were friends with Rome, however, as evidenced by the uprising of the pirate Anicetus (d. 69 CE). Anicetus led a revolt against the newly selected emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) in favor of Vitellius (r. April-December 69 CE). Anicetus was betrayed by his allies and executed in 69 CE and Vespasian went on to become emperor.

Byzantine & Arab Piracy

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, the Eastern Byzantine Empire retained control of the Mediterranean and the slave trade until the rise of Islam in the early 7th century CE. Islam forbade the enslavement of Muslims by Muslims and yet the Arabs relied on slave labor as much as the Byzantines did. In the early stage of the spread of Islam (c. 610-750 CE), non-Muslims who were not killed or converted were sold into slavery. As Islam spread across North Africa and into the Mediterranean, the Arab fleets attacked coastal towns, sacking and burning them, and leaving with a quantity of their citizens for the slave markets. The city of Side fell to the Muslim raiders at some point in the 7th century CE, and by 700 CE they had taken Cilicia entirely from the Byzantines.

The slave trade remained the strongest incentive for piracy and Muslim slave ships prowled the Mediterranean as the Cilicians had before. Crete, under Muslim control as the Emirate of Crete since the 820's CE, was again a haven for pirates who justified their actions as Islamic jihad. It was, in part, the activities of these pirates out of Crete that led to its conquest by the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (r. 963-969 CE) in 961 CE prior to his reclamation of Cilicia, also again associated with piracy, in 965 CE. The slave trade steadily declined in the Byzantine Empire after the 7th century CE as it came to be viewed as morally wrong but slaves were still kept by the Byzantines and were supplied by Arab traders and pirates.

European Christian nations also actively engaged in piracy and the slave trade, in spite of the Byzantine condemnation of both. In 1192 CE, the Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos (l. 1156-1204 CE) complained to the State of Genoa that their pirates had robbed Byzantine ships of substantial goods. Angelos demanded Genoa reimburse the Byzantine merchants for their loss or he would hold the Genoese citizens living in his capital of Constantinople responsible and force them to pay. Angelos' threat does not seem to have had any effect on Genoa or its pirates who continued on as they had before.

Conclusion

Piracy continued in the Mediterranean after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 CE and the rise of the Ottoman Empire. Already by 1198 CE, Muslim piracy and slave trading had become a serious enough issue that the monastic order of the Trinitarians had been founded to ransom European Christians from slavery in the Far East. The Berber pirates of North Africa were the primary agents who would expand their sphere of operations under the privateer Kemal Reis (l. c. 1451-1511 CE) who established the Barbary pirates as a significant menace. Reis was so effective in taking European Christian ships and crews for slaves that he was made an admiral of the Ottoman Empire.

The Barbary pirates kidnapped and sold over 1 million European Christians into slavery between the time of their establishment under Kemal Reis and c. 1830 CE when their central base of operations in Algiers was taken by France. Even this date does not mark the end of piracy in the Mediterranean, however, as it would continue throughout the 19th century CE, on a smaller scale, engaged in by the type of pirate familiar from modern-day novels and films.