The Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644 was a major battle during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). There was no clear winner despite the Parliamentarians having a numerical advantage of 2:1. The seeming lack of coordination between the Parliamentarian commanders at Newbury and the definite lack of progress in destroying the royal army led to Parliament forming a new professional fighting force, the New Model Army, which then prosecuted the war with much more vigour and success.

The Civil War So Far

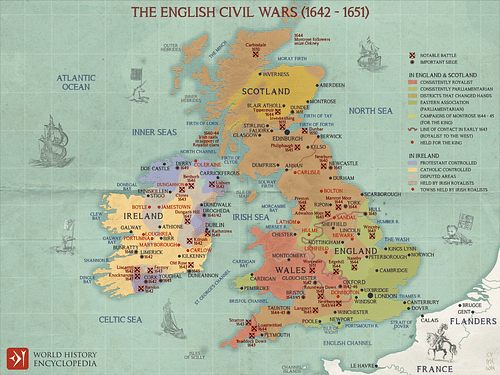

King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) had clashed with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms for years, and, finally, a civil war broke out in 1642. The 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) met in over 600 battles and sieges over the duration of the conflict. From the start, London, the southeast, and the Royal Navy were in the Roundheads' hands while the king controlled the western and northern parts of England. After victories on both sides in the first three years of the war, the king's fortunes took a significant turn for the worse in 1644. Charles had convened his own parliament at his capital Oxford, which helped raise much-needed funds for the war effort. Then a heavy defeat at the Battle of Marston Moor near York on 2 July 1644 was followed by the loss of York later the same month. The Parliamentarians now controlled the entire north of England except for a few isolated castles, and they had found themselves a gifted new commander, one Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), who had led the cavalry with aplomb at Marston Moor.

The Royalists might have been down, but they were certainly not out. The king won the Battle of Lostwithiel in Cornwall in the first days of September, capturing most of the Parliamentarian infantry and 42 artillery pieces into the bargain. This action secured the southwest of the kingdom. However, the Battle of Montgomery in Wales later that month saw yet another victory go to the Parliamentarians. The two sides took a breath and rearranged their forces, ready for another large-scale clash. The site was to be, once again, Newbury in Berkshire, where, back in September 1643, they had fought out a bloody stalemate in the longest battle of the entire Civil War: the First Battle of Newbury.

Roundheads & Cavaliers

Three Parliamentarian armies converged on Berkshire. The three respective commanders were Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (1591-1646), Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester (1602-1671), and Sir William Waller (1597-1668). These were three big personalities, with Essex viewing himself superior to the other two, although neither was willing to be subordinate to him. The lack of cooperation in the Parliamentarian high command was a decisive factor in the events that followed. To achieve some semblance of unified command, a committee was created, which included all three commanders and their highest-ranking officers. How this arrangement might have worked in practice became irrelevant when Essex became seriously ill with stomach problems and could no longer participate in the field.

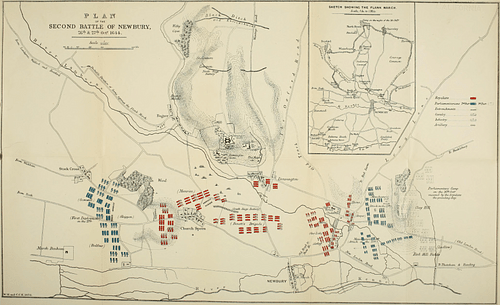

Charles led the royal army in person. It was smaller in number than the enemy's total force, around 8,000 versus 17-19,000 men (around 7,000 of which were cavalry), but the king remained confident. He perhaps thought reports on the enemy's numbers were unreliable, and he hoped to make inroads into them before they had a chance to properly assemble as a single fighting force. Unfortunately, the Royalist armies were themselves tardy in organising themselves, and by the time they had all set up camp near Donnington Castle just north of Newbury on 26 October, the Roundheads were in place, too. The Royalists had chosen their site well and were well-protected by a number of rivers, woods, and ravines. On 25 October, the Royalists began to add temporary fortifications where these natural defences were absent and, to impede the enemy if required, they removed the largest bridge crossing the Lambourn river. The fighting terrain was hampered for both sides by hedges, ditches, several enclosures, lanes, and pockets of woodland.

The Pincers Fail to Close

The Parliamentarians were well-aware of the slowness of the Royalist manoeuvres, but a few probing sorties revealed that the opposition had chosen their dispositions and terrain well. For this reason, the Parliamentarian commanders opted not for a full-frontal attack but to try and catch the opposition in a pincer movement. To this end, Waller led a force to the west and around to the left flank of the Royalists during the afternoon and evening of 26 October. He commanded Essex's infantry, two-thirds or more of the Parliamentarian cavalry, and the militia Trained Bands. At the same time, or so it was planned, Manchester would remain in front and attack the enemy head-on with a smaller force of infantry, cavalry, and dragoons (hybrid infantry-cavalry). The Royalists knew of the pincer plan since Waller did not intend to perform the action in secret or in darkness, which would have been practically impossible. As soon as they saw Waller's force was not interested in cutting off their supply routes to their rear but in attacking them directly, the pincer plan became clear to everyone. As a precaution, the king's army protected its rear and exposed flank as best it could by preparing barricades and deploying a number of artillery pieces with musketeers as support.

In the event, when the moment came in the early morning of 27 October for the jaws of the pincer to close, the Parliamentarians could not coordinate their attack, perhaps because the two armies were several miles apart. Evidence would suggest that it was Manchester's force that dithered, perhaps because the Earl wanted to be sure Waller was occupying the enemy fully before his smaller force was engaged. As a consequence of the delay, the Royalists were able to fight each front in turn. However, Waller's force enjoyed such a numerical superiority it should have been able to deal with the enemy without any assistance from Manchester. This consideration was likely why an otherwise risky pincer movement had been approved in the first place.

Manchester made some inroads with his musketeers across the River Lambourn thanks to having brought along a portable footbridge. The Royalist infantry reserve was then deployed, and they repelled the Parliamentarians back across the river. The reserve then seems to have had the time to aid that part of the army facing Waller, who had crossed the Lambourn in his part of the battlefield in the early afternoon after a short artillery barrage perhaps around 3 pm. It may be that the narrow terrain now worked against the Parliamentarians, who were obliged to bunch up their regiments several deep rather than spread them along a wider front. This development would have significantly reduced the numerical advantage of Waller's army. Indeed, in the post-battle documents (of which there are many but with major discrepancies), several regiments are recorded either as not fighting at all or as not suffering any casualties amongst their officers (i.e. they likely did not fight).

What happened next and how each cavalry and infantry unit performed almost entirely depends on which source is read since there were a great many commanders eager to absolve themselves in writing of any blame after the battle's indecisive conclusion. The Royalist army as a whole was driven back, even if it made some progress in some parts, notably against the Parliamentarian's left cavalry wing commanded by Cromwell and against the right-wing cavalry led by Sir William Balfour. The main infantry clash in the centre saw neither side gain a particular advantage, but the Royalists had been pressed into a smaller area than at the start. Then the imminent departure of daylight halted the battle. The situation remained in the favour of the Parliamentarians since they still enjoyed a great numerical advantage, and once daylight returned, they could press on with their two-pronged attack which the Royalists would not have been able to resist indefinitely. Unfortunately for the Roundheads, the king was not prepared to sit in the trap for very much longer.

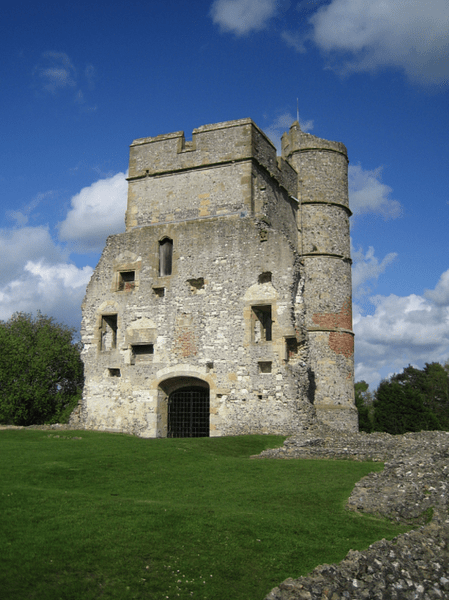

Withdrawal & Donnington Castle

As night fell and a full moon rose, Charles made good his escape from what could have been a death trap. The king, eager for speed before the enemy reacted, left his artillery pieces and wounded safe and sound in Donnington Castle while he moved on to Wallingford. Manchester refused to pursue the king, and the Parliamentarians, surprised by the speed of the withdrawal, debated what to do next over the following week. Charles had time not only to leave Newbury but also to collect reinforcements from Oxford and then return to Donnington. Despite the Parliamentarians besieging the castle, the Cavaliers managed to relieve their comrades and make off with the king's cannons on 9 November. Charles, now with 15,000 troops in the field, had greatly reduced the disparity in numbers between the two sides. Still, the Parliamentarian commanders dithered, and Charles was able to march off in broad daylight with trumpets blaring and flags flying. A golden opportunity to finally crush the Royalist armies had been lost.

Aftermath

The whole episode at Newbury was an exercise in how not to conduct a vigorous prosecution of the war. As the military historian M. Wanklyn puts it, "the Parliamentarian generals were tactically at fault converting a near-certain victory into an embarrassing draw" (204). Following an official inquiry into the events at Newbury, the Earl of Manchester came in for particular criticism for his lack of ambition in engaging the enemy. There were even rumours of questionable loyalty to the cause. Certainly, the king had made some overtures towards Manchester to act as a mediator with Parliament, and the earl had himself stated publicly that defeating Charles in battle did not make him any less the king, whereas heavy defeats for the Parliamentarians would effectively end their claim to rule. These thoughts could explain Manchester's obvious caution in the field. They were not the thoughts, though, of the more aggressive Parliamentarians led by Oliver Cromwell, who was not immune to criticism for his lack of usual energy during the battle at Newbury. It was the more militaristic Parliamentarians who now drove the war forward. In Parliament, Cromwell called for a more professional army and general approach to the war in December 1644.

February 1645 saw the formation of the professional New Model Army by the Parliamentarians. In April, Parliament voted for the Self-Denying Ordinance, a motion which forbade any of its members from also being a military commander. The effect was to remove any commanders who were politically powerful but had no military competence. Waller, Essex, and Manchester were all casualties of this policy. Overall command of the New Model Army was given to a talented and experienced campaigner: Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671). With a standing army that could take the field wherever their commanders thought best and for however long it took to gain victory, the Parliamentarians had taken one of the most important decisions of the entire war. Further, there would be an overarching hierarchy of command for this army and an end to the competition between various commanders and armies fighting in the name of Parliament. The Model Army did its job. A great victory at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire in June 1645 was followed by more victories, including the capture of Bristol. King Charles' situation became utterly desperate, and he was obliged to seek safety in Scotland.