In the mid-2nd century CE, Christianity began a gradual process of identity-formation that would lead to the creation of a separate, independent religion from Judaism. Initially, Christians were one of many groups of Jews found throughout the Roman Empire. The 2nd century CE experienced a change in the demographics, the introduction of institutional hierarchy, and the creation of Christian dogma.

Christianity in the 1st Century CE

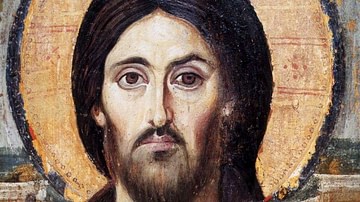

Jesus of Nazareth was a Jewish prophet who preached the imminent kingdom of God (the reign of the God of Israel on earth), which had been predicted in the books of the Jewish prophets. The Prophets claimed that God would intervene to restore Israel to its past glory in the final days. He would raise up a messiah figure (meaning "anointed one"), a descendent from King David (c. 1000 BCE), to lead the movement. After a final battle and the defeat of the nations, there would be a resurrection of the dead, a final judgment, and God would restore the original plan (the Garden of Eden) for the righteous on earth. The wicked would be condemned to annihilation, Gehenna (the Jewish hell).

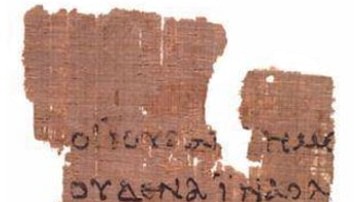

After the death of Jesus, his disciples began teaching his message in Jerusalem and the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean. An important caveat was added; belief in Jesus Christ would result in the resurrection of the individual to a blissful afterlife. With a Jewish message of redemption (described by scholars as 'apocalyptic'), the first missionaries approached Jewish synagogue communities that were established in the Hellenistic period. They would have encountered different groups of Jews who had their individual views of a messiah and the kingdom of God.

We cannot verify the numbers, but apparently, some Jews accepted the claim that Jesus was their messiah, while the majority did not. There are many reasons why most Jews did not join this movement:

- There were various views on the messiah, including his function and his role in God’s plan. The opinions ranged from a warrior-king like David, the embodiment of wisdom, to a pre-existent angelic being in charge of judgment in the final days (e.g. "the son of man" in the Enoch literature).

- The party of the Pharisees had promoted a belief in the resurrection of all the dead, but it would take place in the final days as part of a total scenario. One man emerging from a tomb did not indicate that the times had been fulfilled.

- Many Jews who did look for deliverance from a messiah figure, assumed that this would include the destruction of the current oppressor (Rome), but this did not happen.

- Language involving 'kingdom' was politically dangerous. While Rome was tolerant of various native cults, anything that aroused the crowds for another kingdom was treasonous. Jews had long ago worked out ways in which to co-exist with the Roman government wherever they lived. An edict by Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) had granted the Jewish community permission to follow the customs of their ancestors, an exemption from the state cults. Implicit in the edict was that Jews would not proselytize (seek converts). Jesus had died by crucifixion, the Roman punishment for treason. As Paul the Apostle had written, this was a "stumbling block", and a scandal for both Jews and Gentiles.

- At an early date, to explain the suffering and death of Jesus, Christians turned to the "suffering servant" passages in Isaiah. This servant (symbolic of the nation of Israel at the time) was tortured and killed for the sins of the nation. He was then resurrected by God to share his throne. Christians claimed that the suffering servant was a prediction of Jesus. In Paul’s missions, he taught that this servant was a manifestation of God himself in the form of the earthly Jesus. Christians began to worship Jesus (now deemed the "Christ", (christos in Greek for the Hebrew "messiah") as equivalent to God. Most Jews rejected this deification of Christ.

Missions to the Gentiles (Non-Jews)

In the 1st century CE, Christians were essentially just one more sect of Judaism. A major turning point occurred when something unexpected happened. Gentiles (non-Jews) had often joined in synagogue activities and festivals in these cities. These individuals were designated as "God-fearers" in Acts; those who held respect for the God of Israel but continued to participate in their native cults. As the ancient synagogue in Israel and the diaspora was not a sacred space, there was no bar to their attendance, but synagogues did not actively recruit or seek to convert Gentiles. Some Gentiles would have a place in eschatological Israel (when the kingdom came), but not before that time. Scholars speculate that these Gentiles would have first heard the teachings of Jesus through their presence in synagogues. At the same time, non-God-fearing Gentiles began to show interest.

Due to this unexpected interest, both Paul and Luke reported a meeting in Jerusalem (c. 49 CE) to decide how to include these people. Conversion to Judaism involved the physical identity markers of Jews: circumcision, dietary laws, and the observance of Sabbath. In Acts 15, during the Council of Jerusalem, James, Jesus’s brother, issued the decision that these Gentiles did not have to convert to Judaism. They did, however, have to "abstain from food polluted by idols, from sexual immorality, from the meat of strangled animals and from blood" (Acts 15:19-21). These were ritual and moral purity elements in the Law of Moses. Meat in the public markets were the leftover sacrifices of the temples; Jews shunned anything related to idolatry.

Jewish-Christian Relations in the Earliest Communities

The evidence of Paul’s letters (50s and 60s CE), the gospels, and the Acts of the Apostles indicate that Gentiles rapidly outnumbered Jewish believers. Despite the decree, tensions between Jewish-Christians (those who advocated full conversion) and Gentile-Christians (those who held to the Council of Jerusalem) continued. Paul constantly raged against "false apostles" who traveled to his communities, preaching that Paul was wrong, and the Gentiles should convert (Galatians 1:6-8).

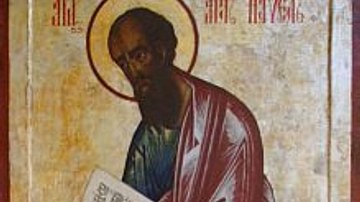

Paul became a believer when he experienced a vision of Jesus in heaven, who commanded him to be "the apostle to the Gentiles" (Galatians 2:8). An earlier Christian had worked out that the delay of the kingdom could be explained with the concept of the parousia ("second appearance"); Jesus, now in heaven, would return to complete the events of the final days.

Paul taught against full conversion for Gentiles, most likely because when these Gentiles were baptized, they received the spirit of God. This was manifest in their "speaking in tongues", healings, and prophesying (Acts 19:6). In other words, God had condoned their admission without Jewish identity markers. However, once included, they had to follow the ethics and morals of the Law of Moses.

A few letters of Paul (Romans, Ephesians, Colossians) are allegedly written when Paul was a prisoner. "Five times I received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods." (2 Corinthians 11:24-25). The "forty lashes" was a synagogue discipline for various violations of the Mosaic Law. Paul provided no details for this punishment, but synagogues did not pressure Gentile adherents to change their traditional lifestyles. Paul now commanded these Gentiles to cease their idolatry ("Flee from the worship of idols" - 1 Corinthians 10:14). This command violated the careful negotiations of Jewish communities with Rome.

The "rods" were used for violations of Roman law. Again, we do not know how or why Paul was beaten, but in the case of Rome, it was most likely Paul’s preaching against idolatry. This was a scandalous concept; ancient views of Roman religion stemmed from the ancestors who received them from the gods. Paul’s views on the impending kingdom, his advocating the worship of Jesus, and his condemnation of idolatry caused tensions both in the synagogues and in the Roman forum.

The Destruction of Jerusalem & the Temple

Beginning with Mark (written c. 70 CE), all four gospels blame the death of Jesus on either the Jewish leadership (the Pharisees and the Sadducees) or collectively the Jews (John’s gospel). In the intervening decades between the death of Jesus and the first gospel, the kingdom did not come. What came instead, was Rome.

The Jews revolted against the Roman Empire in the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE, and in 70 CE, both Jerusalem and the Temple complex were destroyed. The gospel writers blamed the Jews for this disaster because they rejected Jesus as the messiah. The Prophets had consistently condemned Israel for its sins. Israel’s past became the explanation for the present.

With the destruction of the Temple, the traditional rituals could not be carried out. This period marked the beginning of two divergent systems:

- Rabbinic Judaism focused on the analysis and interpretations of their Scriptures

- Christianity began to emerge as a distinct religion from Judaism.

Bishops & Church Fathers

Christians distinguished themselves from both Judaism and the native cults with their election of bishops to lead their communities (as attested in 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus). The early communities based their model on Roman provincial administration, where an 'overseer' (a bishop) was responsible for a section of a province, a diocese.

Unlike priests in the former Temple in Jerusalem and priests in the native cults, Christian bishops had the unique power to forgive sins on earth. Through a ritual of ordination, it was believed that the spirit of God entered these men. It was most likely drawn from the story of Peter laying his hands on the Samaritans in Acts 8. The priests of the native cults as well as the priests at the Temple facilitated repentance and forgiveness, but these actors did not have independent authority to forgive sins. For Jews, only the God of Israel had this power.

By the middle of the 2nd century CE, early Christianity was dominated by leaders who no longer had any ethnic or communal ties to Israel or Judaism. The leaders were Gentile converts who had been educated in the various schools of philosophy. Retrospectively dubbed "the Church Fathers" for their contributions to Christianity, the most prolific writers were: Justin Martyr (Rome, 100-165 CE), Bishop Irenaeus (Lyon, 130-202 CE), and Bishop Tertullian (Carthage, 155-220 CE).

The background in Judaism remained crucially important for the 2nd-century Christian Church. The God of Jesus of Nazareth (and his followers) was the God of Judaism and the Jewish Scriptures. The Christian proclamations had to remain connected to the older ones. The Church Fathers continued to utilize the Jewish Scriptures for their explanations of Christianity and used a common method known as allegory. Allegory is a literary device in which a character, symbol, place, or event is used to create a wider or new meaning. Schooled in the Jewish Scriptures, they applied exegesis, a detailed analysis of a passage to provide a new interpretation. They also used typology or the identification of types in narrative structure. For example, the binding of Isaac became a type that pointed to Jesus on the cross.

Christian Persecution & Adversos Literature

Beginning most likely during the reign of Roman emperor Domitian (r. 81-96), Rome persecuted Christian communities for their atheism, their refusal to participate in the imperial cult. In mandating the imperial cult, Rome became aware that there was a distinct group of people who were not Jews (not circumcised) but also had ceased participation in the ancestral cults. At the same time, conservative Rome had a cultural and religious bias against new religions, particularly those from the East.

The goal of the Church Fathers was to convince Rome that Christians were not new - they were as ancient as Judaism itself - and Christians should have the same exemption from the state cults as the Jews, because Christians were "verus Israel", the true Israel.

The appeal to Rome to have the same exemption from the state cults as the Jews is collectively known as Adversos Literature, or "against the adversaries, the Jews." The writers called upon the polemics of the Prophets (all the sins of the Jews), the gospels, and Paul’s letters. Removing Paul from his historical context, the Church Fathers used Paul’s criticism of Jewish-Christians as a refutation against all Jews and Judaism.

An example of their reinterpretation of Scripture is evident in the story of the Ten Commandments. When Moses received the commandments on Mount Sinai, there were only ten. After he found the Israelites in idolatry, he smashed the tablets. When he went back to get another set, that is when 603 others were added to punish the Jews. Christ had liberated these burdens from true believers, and so Christians only had to follow the first ten.

During the reign of Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), the Jews revolted against Rome under the leadership of Bar Kokhba (135-137). The Bar-Kokhba Revolt, like the first one, ended in disaster. Hadrian renamed Jerusalem with his family name Aelia Capitolina and banned all Jews from living in Jerusalem. Justin Martyr claimed that he met Trypho, a Jewish refugee who had fled to Rome after the revolt. We cannot historically ascertain the existence of this individual; Trypho’s responses and arguments may reflect some early Rabbinic views at the time.

Justin’s dialogue with Trypho became one of the most important of the Adversos texts in defining Christianity against Judaism. He proceeded to teach Trypho the true meaning of the Jewish Scriptures through allegory and exegesis. With the correct allegorical interpretation of the Jewish Scriptures, everywhere that "God" appeared in the texts, it was in fact, the "pre-existent Christ". It was Christ who spoke to Abraham, and when Moses heard the voice from the burning bush, this was Christ in an earlier manifestation of God on earth. Through his methods, he demonstrated that all the Prophets of Israel had predicted the coming of Christ as the savior. God sent Christ into the world to undo the corrupt practices of the Jews, and as proof, he pointed to the fact that God had permitted Rome to defeat the Jews twice. Added to their corruption, the Jews were now charged with the crime of deicide (the killing of God).

Justin declared Christians as "verus Israel" and so Christians had usurped the place of the Jews as God’s chosen. Because of this, Jews no longer had the capacity to correctly interpret their own Scriptures. This is when the Old Testament became joined to the New Testament (the Christians’ sacred texts) as the complete understanding of God’s divine plan. From this moment in time, Christians promoted supersession or replacement theology. God had replaced his protection and favor of the Jews with the Christians.

Jews as Heretics

The Church Fathers also invented the twin concepts of orthodoxy (correct belief) and heresy (from the Greek haeresis, meaning a "school of thought"). In Bishop Irenaeus’ five-volume work, Against All Heresies, the Jews were the first to be denounced as heretics because "they follow their father, the Devil" (4, 6). The Prophets were exempted from this demonization of the Jews; they were proto-Christians because they predicted Christ.

Despite all these arguments, Rome did not recognize Christians as true Jews; Gentile Christians were not circumcised. Persecution only stopped after Constantine’s Conversion to Christianity in 312 CE, when he adopted the views of the Church Fathers.

Absent from the writings of the Church Fathers is evidence of contemporary relations between Jews and Christians in the communities themselves. Their polemical arguments were always drawn from the Scriptures. Beyond the views of their leaders, Jews and Christians apparently continued the ancient practice of ethnic cults mixing with each other. The Council of Elvira in Spain (312 CE) condemned Christians for having Rabbis bless their fields. In an Easter sermon in 386 CE, Bishop John Chrysostom in Antioch railed against his Christians for attending the synagogue on Saturday and then coming to church on Sunday. These writings can also be understood as an attempt to stop such mixing. The unfortunate dark side of this period was the continuing application of the Church Fathers’ views that contributed to Christian antisemitism in the Middle Ages and during the Reformation, and beyond.

Christianity as a New Religion

Christianity borrowed concepts from both Judaism and the native cults in their ideas of the universe, sacrifices, prayers, and rituals. Intellectually, they utilized the concepts and jargon of philosophy to argue the universal nature of Christianity for humankind. But Christianity also differed from ancient systems; the elevated power of their clergy was unique. All ancient cultures had their views on the afterlife, but Christians guaranteed a blissful journey through membership in their communities. Simultaneously old (the God of Israel) and yet new (no idolatry), Christianity became an entirely new system to understand one’s place in the universe.

The contributions of the Church Fathers are significant for what became Christian dogma, or a set of principles that are incontrovertibly understood as true. Their ideas were eventually incorporated into the Nicene Creed (325 CE), a statement of what all Christians should believe. In 381 CE, Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) issued an edict that made Christianity the only legitimate religion in the Roman Empire. In Christian tradition, this is known as the triumph of Christianity.