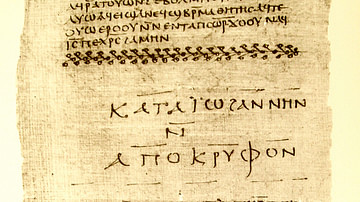

The story of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus Christ is reenacted every year by Christians all over the world in the Easter liturgy. The story has become an essential article of faith and is rarely questioned by New Testament scholars and historians. The full story first appeared in the New Testament Gospel of Mark, followed by Matthew, Luke, and John. That the story appears in all four gospels does not indicate four separate historical sources; Mark established the template for the story, while Matthew, Luke, and John added variations as well as newer material.

Last Supper & Betrayal by Judas Iscariot

In Mark, Matthew, and Luke, the Last Supper was held on the first night of Passover. Passover was one of the major pilgrimage festivals in Jerusalem and thousands of Jews traveled to the city to celebrate it. There was a ritual meal that was reenacted, consisting of a slaughtered lamb and other foodstuffs. This is the meal where Jesus identified his betrayer, Judas Iscariot. The story of Jesus and his disciples celebrating Passover is credible, but many of the other details appear much more as exaggerations. There is an incredible amount of activity taking place that night as well as the next morning, many of which pose historical problems.

We know virtually nothing about Judas. The name Judas was popular and reflected one of the national heroes, Judas Maccabeus who helped to lead the Maccabean Revolt against the Greek occupation (167 BCE). The surname remains a puzzle, although it could indicate that he was from Kerioth, in Judea. There is also a theory that it relates to the word sicarri, the “daggermen” among the Zealots whom many blamed for the Jewish Revolt. He was listed as one of the original disciples, but Luke and John claimed that Satan possessed him. There is an allusion to Psalm 41:9: "Even my close friend, someone I trusted, one who shared my bread, has turned against me."

The story of Judas appears first in Mark's gospel (70 CE); we can find no earlier evidence of a story of

betrayal or this individual. In 1 Corinthians 15:5, Paul listed several resurrection appearances by Jesus, writing "He [Jesus] appeared to Cephas [Peter] and then to the twelve,” but would Judas have been honored with a resurrection appearance if he had betrayed Jesus? In 1 Cor. 11:23, when Paul related the eucharistic formula, he began with, “...on the night when he was handed over...” Every English Bible translates “handed over” as “betrayed”, but the Greek word here simply means “handed over to the authorities” and so this is not a prooftext for the story of Judas.

After the meal, Jesus and the disciples walk over to a place known as Gethsemane (“olive press”). The story is known as the Agony in the Garden” where Jesus prayed to be able to avoid his upcoming death and torture. Since Jesus' disciples kept falling asleep and he had to wake them three times, the question remains: who took notes of this episode? We can, however, find an interesting parallel in the earlier story of Ahitophel, a courier of King David's who joined his son Absalom's rebellion against the king. In this passage, David had sought refuge on the Mt. of Olives (the location of Gethsemane), “discouraged and weeping”:

Let me choose twelve thousand men, and I will set out and pursue David tonight. I will come upon him when he is weary and discouraged and throw him into a panic; and all the people with him will flee. I will strike down the king only. You seek the life of only one man, and all the people will be at peace. (2 Samuel 17:1-4)

The Arrest

According to the betrayal story of the gospels, Judas offered to lead the Jewish authorities to where Jesus could be arrested that night in secret and he betrayed Jesus with a kiss, a reference to Proverbs 27:6. (“Well meant are the wounds of a friend that afflicts, but profuse are the kisses of an enemy”). When the arresting agents - "the chief priests, scribes, and elders" in Mark, the "chief priests and elders of the people" in Matthew, the "temple guards" in Luke, or "a Roman auxiliary" in John - appeared, the disciples scattered in a panic and abandoned Jesus to his fate, “fulfilling” what Jesus had predicted throughout the ministry in Mark.

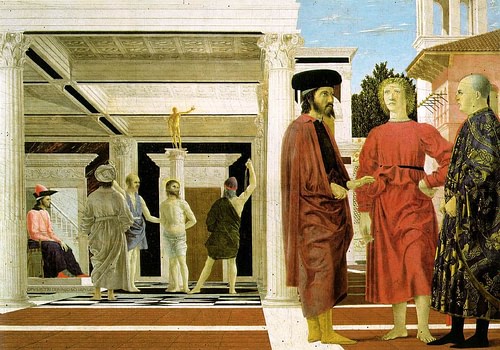

According to Mark, Jesus was taken before the entire Sanhedrin, the city council of Jerusalem while in Luke and John, it is the high priest's house (Annas and his son-law, and his son Caiaphas). Mark and Matthew mention only one trial at night, while Luke included a separate trial in front of Herod Antipas (in town for Passover), as Pilate recognized that Jesus was from Herod's territory (the Galilee), and not Judea.

The problem here is that Passover was a family holiday. Would the entire Sanhedrin (and the high priest!) get up and leave their families, first as a group to arrest him, and second, for a trial of a Galilean wonder-worker? According to later Rabbinic tradition, Jewish law forbade trials at night or on holidays. If indeed they perceived that Jesus and his followers threatened the Temple in some way, they could have just placed him in a holding cell until the end of the holiday.

Blasphemy?

Mark claimed that when Jesus was accused, the “witnesses did not agree.” Again, Jewish Law dictated that in such an event, the case had to be thrown out. This was Mark's way of saying that it was an illegal trial and that Jesus was framed. This was Mark's major theme throughout the ministry, that from the very beginning his opponents (the Pharisees and the Herodians) had sought his death.

The high-priest then asked, “Are you the messiah, the son of the blessed one?” and Jesus answered, “I am. And you will see the son of man seated at the right hand of the power and coming with the clouds of heaven” (quoting Daniel 7:13-14). The high priest tore his clothes (a sign of mourning), declared this statement 'blasphemy', and the council condemned him to death. Blasphemy meant slander. In Judaism, this consisted of breaking an oath taken in the name of god and idolatry and the punishment was stoning. Simply claiming “messiahship” was not a crime; Josephus (the 1st-century CE Jewish historian) related stories of several who claimed to be the messiah and, as far as we know, none of them were executed under Jewish Law. Many were executed by Rome, usually because they had stirred up the mobs against the Roman government. Mark knew how Jesus died and so the plot required that the Jewish leaders hand Jesus over to Rome for crucifixion.

John's gospel provided a more credible reason for the arrest. According to John, the raising of Lazarus stirred up the crowd and the high priest decided that Jesus had to be killed to avoid the Romans stepping and making them appear as if they could not control the Temple crowds. Caiaphas announced: “You do not understand that it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed” (John 11:50). This aligns with the story of Ahitophel: “You seek the life of only one man, and all the people will be at peace”.

Pontius Pilate & Release of Barabbas

Chronologies of Jesus place his death between 26-36 CE, as this is when Pontius Pilate served in Judea during the reign of Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE). For all the festivals, Pilate would have come to Jerusalem to oversee law and order. We have two sources on Pilate, the writings of Philo of Alexandria (writing in the 30s and 40s CE) and Flavius Josephus. Both listed Pilate's abuses of power and corruption in Judea. However, we always should be careful in how we analyze such sources. Both writers argued that the problems with Jewish unrest in Jerusalem and the other cities was caused by corrupt governors, and not Jews.

Mark claimed that Pilate had a habit of releasing a prisoner at the Passover festival, however, in all the research done on Pilate, there is no evidence of this. The name of the prisoner was Barabbas, an Aramaic name that means “son of the father.” Mark ironically had the Jews cry out for the release of the wrong “son of the father”. Narratively, the story is a mess. Is this the same crowd who welcomed Jesus into the city a few days earlier as their deliverer? The same crowd that the priests feared would riot so that they had to arrest Jesus “in secret” at night? Mark provides no details as to the identity of this group or why they turned against Jesus.

The manner of Jesus' death suggests he died as a traitor to Rome. The followers of Jesus had to undo this, and the best way was to have a Roman magistrate declare Jesus innocent of rebellion. By implication, his followers were also innocent of this charge, unlike the other Jews in the recent Jewish Revolt against Rome.

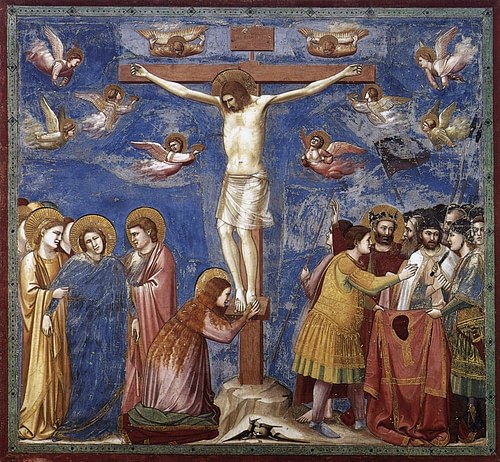

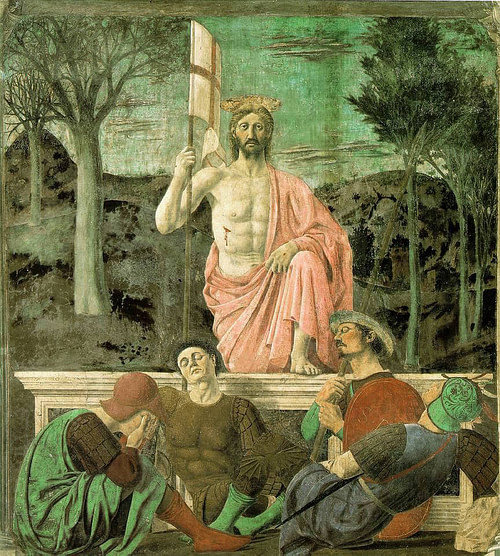

Crucifixion

There is no doubt that Mark and the others were witnesses to crucifixions by Rome, but not necessarily witnesses to this one. In Roman crucifixions, the prisoners were flogged first and then carried the cross-beam (not the entire cross; they were too heavy). Soldiers had the authority to force a bystander to carry the beam when the prisoner flagged. The “gall and vinegar” on a sponge was to stimulate the victim when he fainted. Mark incorporated Psalms of lament and the “suffering servant” passages from the book of Isaiah. The allusions demonstrate that all of this was 'predicted' in the Scriptures.

Mark also reported that “the chief priests and scribes” were there, mocking Jesus. This is another problematic detail. At Passover, one had to remain free from corpse contamination for the week-long festival. The priests would not jeopardize their participation in the rest of the festival by literally going to the killing fields. This is simply a polemical construction.

Romans crucified victims along the roads leading into cities where they served as propaganda - this is what happens when you rebel against Rome. They attempted to keep the victim alive as long as possible (hence, the vinegar stimulants) to demonstrate how rebels would suffer extreme torture. The average time of survival was approximately anywhere from three to five days. The cause of death is a combination of not being able to lift yourself up enough to breath (asphyxiation), as well as loss of blood, pain, and trauma. Jesus died within three hours. This detail was driven largely by the narrative plot, to get him into the grave before Sabbath began at sundown. Funeral preparations could not be completed until after the Sabbath, which is why the women go to the tomb on Sunday morning.

When Rome punished criminals, they wanted it to last for eternity; crucifixion victims were denied traditional funeral rituals. The narrative function of Joseph of Arimathea is to ensure that this did not happen to Jesus. On the other hand, Roman magistrates were notorious for accepting bribes. John filled out this detail when he said that Joseph asked Pilate for the body (John 19:38).

The tradition had Jesus in the tomb for three days. Yet, if counting sunset to sunset (Friday evening to Sunday morning), it was only one day and a morning. Nevertheless, the gospels all have references to three days in the predictions, as in Matthew with his analogy of Jonah and the whale. When Matthew claimed that believers would receive a “sign,” it was the “sign of Jonah, in the belly of the whale for three days.” Jews believed that the body did not begin to physically decay until the “fourth day” after death and Jesus could not emerge with what would have been “corpse contamination.”

What Really Happened

We may never be able to answer that question with certainty. We can attempt a reconstruction of probable events through everything we know concerning the rule of the Roman Empire in the provinces, various issues debated among Jews at the time, and the charged elements that were in the air in hopes for God's final intervention.

If Jesus went to Jerusalem for Passover, some followers most likely went as well, and he probably picked up several more in the city. If the pilgrims welcomed him as a messiah figure, this would have alerted the legions and the priests to potential trouble. The combination of Jesus preaching a 'kingdom' that was not Rome's with a crowd of followers at festival time is most likely what got him killed. We cannot verify a betrayal by Judas. His story is so embedded in scriptural references that it remains difficult to sort out probable events, but one suggestion is that “Judas” is personified as “the Jews” who refused to accept Jesus as the messiah.

If Jesus had tried to disrupt the services in the Temple, the priesthood, in prior arrangement with the Roman procurator, would have immediately turned him over. This would be the extent of any involvement in the death of Jesus by the Jewish leadership, the holiday would preclude any Jewish trials described in the gospels. Once handed over, immediate crucifixion by Rome would follow. It is very unlikely that there was a trial before Pilate, who was also known for not granting trials to Roman citizens. Would he have bothered with a trial for a Jewish peasant?

The Legacy of the Trial & Crucifixion of Jesus

For his followers, the death of Jesus must have been an enormously traumatic shock. To explain it, they did what all Jews had done for centuries; they turned to the Scriptures for an answer and found scapegoats to blame. Within 20 years after the death of Jesus, his followers (Peter, James, and John) established a Christian community in Jerusalem. We know this because Paul visited them there. Both Paul and Luke described a major meeting of the missionaries in Jerusalem, perhaps c. 49 CE.

Over the next few decades, the followers of Jesus attempted to create their own identity vis-à-vis Judaism. In addition to the gospels, New Testament texts and letters utilized the argument that only Christians had the correct interpretation of the Jewish Scriptures. By the 2nd century CE, the vitriol increased as the Church Fathers used the gospel material to demonize the Jews as agents of the Devil, now charged with the killing of God. This is the origin of Christian antisemitism in the Middle Ages and during the Reformation, and beyond.

In relation to theology and spirituality, the suffering and death of Jesus became the template for selfless sacrifice and is at the core for understanding how this death could transform believers. Exploring the historicity of this story does not challenge faith, but reading the gospels as history without the criteria we apply to the reading of all ancient history remains problematic.