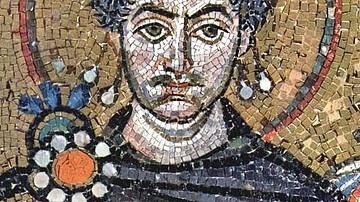

The Plague of Justinian (541-542 CE and onwards) is the first fully documented case of bubonic plague in history. It is named for the emperor of the Byzantine Empire at the time, Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) and recorded by his court historian Procopius (l. 500-565 CE) in his History of the Wars, Book II. 22. The plague is thought to have originated in China, traveled to India, and then through the Near East before it entered Egypt, which is where Procopius claims it came from to Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire.

By the time the plague had run its course – c. 750 CE – the death toll was upwards of 30 million with the standard figure of 50 million agreed upon by most scholars. It had been working its way through the Near East prior to reaching Constantinople but it seems the Byzantines had no idea it had anything to do with them and so made no provision against it. As Procopius observes, however, there would have been little they could have done since they had no idea how the disease was spread. The only defense they could mount took the form of religious rituals, for the most part, which proved ineffective and the plague wound up taking 25% of the population.

Background to the Plague

The cause of plague was not isolated and identified until 1894 CE as the bacterium Yersinia pestis which was carried by the fleas on rodents, primarily rats. Prior to this identification, the disease was attributed to supernatural causes and, in the case of Justinian's Plague, the wrath of God. Procopius, in his Anecdota (better known as Secret History), condemns Justinian I's reign as unjust and capricious, claiming he was controlled by his passions – and his wife Theodora – and strongly suggests God was displeased with him.

Procopius notes how, even when the plague was raging, Justinian I demanded tax assessment and collection, charging survivors exorbitant rates to make up for those who had died (Anecdota XXIII.20). These taxes then went to Justinian I's building projects, not provision for the sick and dying, and so the emperor is singled out by Procopius as the most obvious cause for God's wrath; the people suffered simply as collateral damage.

Justinian I did become infected but survived the plague, while most did not, which must have enraged Procopius further. Even so, as he notes, there was no reason why the disease attacked one person and not another, no understanding as to why one survived and another died, and no treatment which worked with one that would then help save any others. The plague entered the city through trade – most likely arriving with the rats on grain ships out of Egypt – and spread quickly through Constantinople. The only effective measure taken was what is known today as social distancing and self-isolation, both initiated by the people themselves, not by Justinian I's administration.

The Text

Procopius' text details the origin, symptoms, spread, and reaction to the plague, also offering his observation that it was sent by God. The following version, slightly edited for space (indicated by ellipses) is taken from his History of the Wars, Book II.22, translated by H. B. Dewing for the Loeb Library Collection, 1914 CE, as given by editor Jon E. Lewis in The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Ancient Rome:

During these times there was a pestilence by which the whole human race came near to being annihilated. Now in the case of all other scourges sent from heaven some explanation of a cause might be given by daring men, such as the many theories propounded by those who are clever in these matters; for they love to conjure up causes which are absolutely incomprehensible to man, and to fabricate outlandish theories of natural philosophy knowing well that they are saying nothing sound but considering it sufficient for them, if they completely deceive by their argument some of those whom they meet and persuade them to their view. But for this calamity it is quite impossible either to express in words or to conceive in thought any explanation, except indeed to refer it to God. For it did not come in a part of the world nor upon certain men, nor did it confine itself to any season of the year, so that from such circumstances it might be possible to find subtle explanations of a cause, but it embraced the entire world, and blighted the lives of all men, though differing from one another in the most marked degree, respecting neither sex nor age.

For much as men differ with regard to places in which they live, or in the law of their daily life, or in natural bent, or in active pursuits, or in whatever else man differs from man, in the case of this disease alone the difference availed naught. And it attacked some in the summer season, others in the winter, and still others at the other times of the year. Now let each one express his own judgment concerning the matter, both sophist and astrologer, but as for me, I shall proceed to tell where this disease originated and the manner in which it destroyed men.

It started from the Egyptians who dwell in Pelusium. Then it divided and moved in one direction towards Alexandria and the rest of Egypt, and in the other direction it came to Palestine on the borders of Egypt; and from there it spread over the whole world, always moving forward and travelling at times favorable to it. For it seemed to move by fixed arrangement, and to tarry for a specified time in each country, casting its blight slightingly upon none, but spreading in either direction right out to the ends of the world, as if fearing lest some corner of the earth might escape it. For it left neither island nor cave nor mountain ridge which had human inhabitants; and if it had passed by any land, either not affecting the men there or touching them in indifferent fashion, still at a later time it came back; then those who dwelt round about this land, whom formerly it had afflicted most sorely, it did not touch at all, but it did not remove from the place in question until it had given up its just and proper tale of dead, so as to correspond exactly to the number destroyed at the earlier time among those who dwelt round about. And this disease always took its start from the coast, and from there went up to the interior.

And in the second year it reached Byzantium in the middle of spring, where it happened that I was staying at that time. And it came as follows. Apparitions of supernatural beings in human guise of every description were seen by many persons, and those who encountered them thought that they were struck by the man they had met in this or that part of the body, as it havened, and immediately upon seeing this apparition they were seized also by the disease. Now at first those who met these creatures tried to turn them aside by uttering the holiest of names and exorcising them in other ways as well as each one could, but they accomplished absolutely nothing, for even in the sanctuaries where the most of them fled for refuge they were dying constantly. But later on they were unwilling even to give heed to their friends when they called to them and they shut themselves up in their rooms and pretended that they did not hear, although their doors were being beaten down, fearing, obviously, that he who was calling was one of those demons. But in the case of some the pestilence did not come on in this way, but they saw a vision in a dream and seemed to suffer the very same thing at the hands of the creature who stood over them, or else to hear a voice foretelling to them that they were written down in the number of those who were to die. But with the majority it came about that they were seized by the disease without becoming aware of what was coming either through a waking vision or a dream.

And they were taken in the following manner. They had a sudden fever, some when just roused from sleep, others while walking about, and others while otherwise engaged, without any regard to what they were doing. And the body showed no change from its previous color, nor was it hot as might be expected when attacked by a fever, nor indeed did any inflammation set in, but the fever was of such a languid sort from its commencement and up till evening that neither to the sick themselves nor to a physician who touched them would it afford any suspicion of danger. It was natural, therefore, that not one of those who had contracted the disease expected to die from it. But on the same day in some cases, in others on the following day, and in the rest not many days later, a bubonic swelling developed; and this took place not only in the particular part of the body which is called boubon, that is, "below the abdomen," but also inside the armpit, and in some cases also beside the ears, and at different points on the thighs.

Up to this point, then, everything went in about the same way with all who had taken the disease. But from then on very marked differences developed; and I am unable to say whether the cause of this diversity of symptoms was to be found in the difference in bodies, or in the fact that it followed the wish of Him who brought the disease into the world. For there ensued with some a deep coma, with others a violent delirium, and in either case they suffered the characteristic symptoms of the disease. For those who were under the spell of the coma forgot all those who were familiar to them and seemed to lie sleeping constantly. And if anyone cared for them, they would eat without waking, but some also were neglected, and these would die directly through lack of sustenance. But those who were seized with delirium suffered from insomnia and were victims of a distorted imagination; for they suspected that men were coming upon them to destroy them, and they would become excited and rush off in flight, crying out at the top of their voices. And those who were attending them were in a state of constant exhaustion and had a most difficult time of it throughout. For this reason, everybody pitied them no less than the sufferers…because of the great hardships which they were undergoing. For when the patients fell from their beds and lay rolling upon the floor, they kept putting them back in place, and when they were struggling to rush headlong out of their houses, they would force them back by shoving and pulling against them…

Death came in some cases immediately, in others after many days; and with some the body broke out with black pustules about as large as a lentil and these did not survive even one day, but all succumbed immediately. With many also a vomiting of blood ensued without visible cause and straightway brought death. Moreover, I am able to declare this, that the most illustrious physicians predicted that many would die, who unexpectedly escaped entirely from suffering shortly afterwards, and that they declared that many would be saved, who were destined to be carried off almost immediately. So it was that in this disease there was no cause which came within the province of human reasoning; for in all cases the issue tended to be something unaccountable. For example, while some were helped by bathing, others were harmed in no less degree. And of those who received no care many died, but others, contrary to reason, were saved. And again, methods of treatment showed different results with different patients. Indeed the whole matter may be stated thus, that no device was discovered by man to save himself, so that either by taking precautions he should not suffer, or that when the malady had assailed him he should get the better of it; but suffering came without warning and recovery was due to no external cause. And in the case of women who were pregnant death could be certainly foreseen if they were taken with the disease. For some died through miscarriage, but others perished immediately at the time of birth with the infants they bore. However, they say that three women in confinement survived though their children perished, and that one woman died at the very time of childbirth but that the child was born and survived…

Now the disease in Byzantium ran a course of four months, and its greatest virulence lasted about three. And at first the deaths were a little more than the normal, then the mortality rose still higher, and afterwards the tale of dead reached five thousand each day, and again it even came to ten thousand and still more than that. Now in the beginning each man attended to the burial of the dead of his own house, and these they threw even into the tombs of others, either escaping detection or using violence; but afterwards confusion and disorder everywhere became complete. For slaves remained destitute of masters, and men who in former times were very prosperous were deprived of the service of their domestics who were either sick or dead, and many houses became completely destitute of human inhabitants. For this reason, it came about that some of the notable men of the city because of the universal destitution remained unburied for many days…

And when it came about that all the tombs which had existed previously were filled with the dead, then they dug up all the places about the city one after the other, laid the dead there, each one as he could, and departed; but later on those who were making these trenches, no longer able to keep up with the number of the dying, mounted the towers of the fortifications in Sycae, and tearing off the roofs threw the bodies there in complete disorder; and they piled them up just as each one happened to fall, and filled practically all the towers with corpses, and then covered them again with their roofs. As a result of this an evil stench pervaded the city and distressed the inhabitants still more, and especially whenever the wind blew fresh from that quarter.

At that time all the customary rites of burial were overlooked. For the dead were not carried out escorted by a procession in the customary manner, nor were the usual chants sung over them, but it was sufficient if one carried on his shoulders the body of one of the dead to the parts of the city which bordered on the sea and flung him down; and there the corpses would be thrown upon skiffs in a heap, to be conveyed wherever it might chance. At that time, too, those of the population who had formerly been members of the factions laid aside their mutual enmity and in common they attended to the burial rites of the dead, and they carried with their own hands the bodies of those who were no connections of theirs and buried them. Nay, more, those who in times past used to take delight in devoting themselves to pursuits both shameful and base, shook off the unrighteousness of their daily lives and practiced the duties of religion with diligence, not so much because they had learned wisdom at last nor because they had become all of a sudden lovers of virtue, as it were—-for when qualities have become fixed in men by nature or by the training of a long period of time, it is impossible for them to lay them aside thus lightly, except, indeed, some divine influence for good has breathed upon them—-but then all, so to speak, being thoroughly terrified by the things which were happening, and supposing that they would die immediately, did, as was natural, learn respectability for a season by sheer necessity. Therefore, as soon as they were rid of the disease and were saved, and already supposed that they were in security, since the curse had moved on to other peoples, then they turned sharply about and reverted once more to their baseness of hearts…

And work of every description ceased, and all the trades were abandoned by the artisans, and all other work as well, such as each had in hand. Indeed, in a city which was simply abounding in all good things, starvation almost absolute was running riot. Certainly, it seemed a difficult and very notable thing to have a sufficiency of bread or of anything else; so that with some of the sick it appeared that the end of life came about sooner than it should have come by reason of the lack of the necessities of life…

Such was the course of the pestilence in the Roman empire at large as well as in Byzantium. And it fell also upon the land of the Persians and visited all the other barbarians besides.

Conclusion

Another eyewitness to the plague, John of Ephesus (l. c. 507 - c. 588 CE) corroborates Procopius' account and also notes that the people of Constantinople were aware of the plague for two years before it reached the city but made no effort to prepare themselves for its arrival. When the plague moved on, crops were left rotting in the fields, inflation soared, and Justinian I continued to scramble to gather the taxes he needed for his building projects, notably churches, which he seems to have thought would please God who would then keep another such pestilence from ravaging his empire.

After leaving Constantinople, the plague returned to the Near East – “the land of the Persians” – and destroyed the population there up through 749 CE before dying down to then flare up in the Black Death which struck the East 1346-1360 CE and Europe 1347-1352 CE. As with these later pandemics, Justinian's Plague caused widespread panic and disruption, damaging the economy, the military, and every other aspect of life in the Byzantine Empire and beyond. Procopius notes above how “the whole human race came near to being annihilated” and, from the perspective of his time, the event could not have been interpreted in any other way.