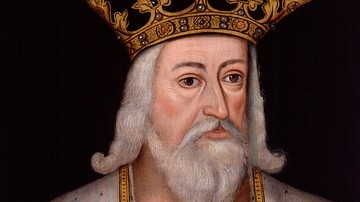

The Battle of Crécy on 26 August 1346 CE saw an English army defeat a much larger French force in the first great battle of the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453 CE). Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE) and his son Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376 CE) led their professional army to victory thanks to a good choice of terrain, troop discipline in the heat of battle, use of the devastating weapon the longbow, and the general incompetence of the French leadership under King Philip VI of France (r. 1328-1350 CE). Crécy would be followed up by an even more impressive victory at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 CE as England got off to a flier in a conflict that would rumble on for 116 years.

The Hundred Years' War

In 1337 CE Edward III of England was intent on expanding his lands in France and he had the perfect excuse as via his mother Isabella of France (b. c. 1289 CE and the daughter of Philip IV of France, r. 1285-1314 CE), he could claim a right to the French throne as nephew of Charles IV of France (r. 1322-1328 CE). Naturally, the current king, Philip VI, was unwilling to step down and so the Hundred Years' War between France and England began. The name of the conflict, derived from its great length, is actually a 19th-century CE label for a war which proceeded intermittently for well over a century, in fact, not finally ending until 1453 CE.

The first major action of the wars was in June 1340 CE when Edward III destroyed a French fleet at Sluys in the Low Countries. Next, an army led by the Earl of Derby recaptured Gascony for the English Crown in 1345 CE. Then, to prepare for a field campaign in French territory, Edward III's eldest son, Edward of Woodstock, aka Edward the Black Prince, was charged with torching as many French towns and villages as he could along the Seine Valley through July 1346 CE. This strategy, known as chevauchée, had multiple aims: to strike terror into the locals, provide free food for an invading army, acquire booty and ransom for noble prisoners, and ensure the economic base of one's opponent was severely weakened, making it extremely difficult for them to later put together an army in the field. Inevitably, ordinary troops also took the opportunity to cause general mayhem and loot whatever they could from the raids. This was a brutal form of economic warfare and, perhaps, too, it was designed to provoke King Philip into taking to the field and facing the invading army, which is exactly what happened.

Troops & Weapons

Both sides at Crécy had heavy cavalry of medieval knights and infantry but it would be the English longbow that proved decisive - then the most devastating weapon on the medieval battlefield. These longbows measured some 1.5-1.8 metres (5-6 ft.) in length and were made most commonly from yew and strung with hemp. The arrows, capable of piercing armour, were about 83 cm (33 in) long and made of ash and oak to give them greater weight. A skilled archer could fire arrows at the rate of 15 a minute or one every four seconds. The English army also included a contingent of mounted archers which could pursue a retreating enemy or be deployed quickly where they were most needed on the battlefield.

The French, although they had some archers, relied more on crossbowmen as firing a crossbow required less training to use. The main contingent in Philip's army was composed of Genoese crossbowmen. The crossbow, though, had a seriously slower firing rate than the longbow, about one bolt to five arrows in terms of speed of delivery.

In terms of infantry, the better-equipped men-at-arms wore plate armour or stiffened cloth or leather reinforced with metal strips. Ordinary infantry, usually kept in reserve until the cavalry had clashed, had little armour if any and wielded such weapons as pikes, lances, axes, and modified agricultural tools. Finally, Edward's army did boast some crude cannons - the first to be used on French soil - although their impact would have been limited given the poor technology of the period as they could not, for example, fire downhill.

Battle

On 26 August 1346 CE the two armies met proper, after a few skirmishes along the way, near Crécy-en-Ponthieu, a small town south of Calais. King Edward, leading his army in person, had landed at Saint-Vaast-La-Hougue near Cherbourg on 12 July and then marched eastwards. The king met up with the Black Prince's force and, perhaps as a reward for his successful raids, the prince was knighted by his father. Caen was then captured on 26 July, and the invading army turned north at Poissy just west of Paris to finally arrive near Crécy. King Philip, meanwhile, led his army from nearby Abbeville.

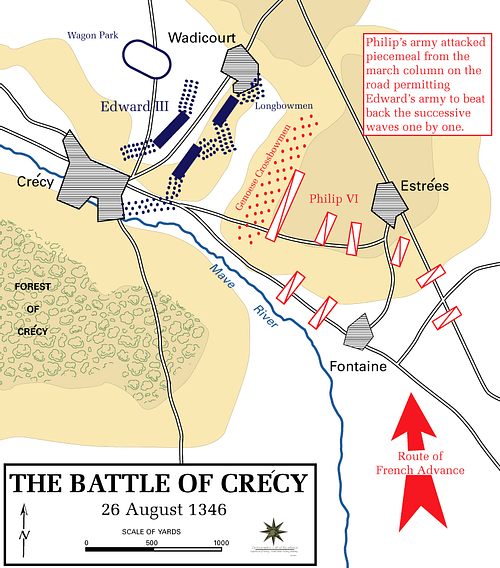

The numbers at the battle of Crécy are disputed, but historians agree the English army was significantly smaller than the French, perhaps around 12,000 against 25,000 men. Some historians put Edward's army at 15,000 men. King Edward's army attempted to overcome their numerical disadvantage by taking a defensive position on a small rise overlooking the River Maie. Edward's force was split into three divisions and the flanks were protected on one side by a forest and marshy ground, and on the other by the small village of Wadicourt. The French would have to both narrow their lines of troops and attack uphill. Edward made things even more difficult for the enemy cavalry by having holes dug into the open ground in front of his own lines.

Just before the battle commenced, the English king gave a rousing speech to his troops, at least according the medieval chronicler Jean Froissart (c. 1337 - c. 1405 CE):

Then the king leapt on a palfrey with a white rod in his hand…he rode from rank to rank, desiring every man to take heed that day to his right and honour. He spake it so sweetly and with so good countenance and merry cheer that all such as were discomfited took courage in the seeing and hearing of him.

(quoted in Starkey, 231)

The French cavalry charged first but got into a muddle when the order to advance was given but then retracted as the French king realised they were charging directly into a low, late-afternoon sun. Some French cavalry carried on moving forward regardless while others retreated. The Genoese crossbowmen employed by King Philip then advanced to the accompaniment of drums and trumpets but quickly broke their ranks after they realised they were fully exposed to the enemy archers. The French king, seeing the retreat of the Genoese, ordered his own cavalry to charge at and through them causing even greater confusion. The French heavy horse then continued to attack in waves, but the Welsh and English archers, possibly positioned on the flanks of the English men-at-arms, proved devastating.

Edward was using the very same troop formation that had won him his success at Halidon Hill against the Scots back in 1333 CE. French knights were knocked off their horses and had their armour pierced by the powerful English arrows coming at them from multiple directions. The French simply could not find an answer to the range, power, and accuracy of the English longbow. As the battle wore on and became more confused, King Edward's army benefitted from its greater battle experience and discipline, gained the hard way through fighting in Scotland and Wales.

As many as 15 waves of French cavalry attacks were driven back, and the English discipline ensured that nobody broke from their defensive formation to recklessly pursue the fleeing cavalry where they would surely have been cut down by the numerically superior French infantry in the rear. In contrast, although the French knights and their European allies were experienced, Philip's infantry was composed of poorly trained and unreliable militia, and even the knights proved totally ill-disciplined. The English king then gained further mobility by having his knights dismount and proceed towards the enemy in tight ranks supported by pikemen and with a vanguard of archers.

Prince Edward, then aged just 16, led the English army's right wing alongside Sir Godfrey Harcourt. The prince fought with aplomb, but there had been a moment of great danger when the French seemed about to overwhelm the Prince's troops. Sir Godfrey called for reinforcements but, according to the medieval chronicler Jean Froissart (c. 1337 - c. 1405 CE), writing in his Chronicles, on hearing of his son's plight King Edward, who was watching the proceedings from a handy vantage point by a windmill, merely stated that if his son could extricate himself from his difficulties then he would win his spurs that day (spurs being a mark of knighthood and presumably to be awarded to Edward in his full knighting ceremony when he got back home). The Black Prince was ultimately saved by his standard-bearer Richard Fitzsimon, and the French were driven back.

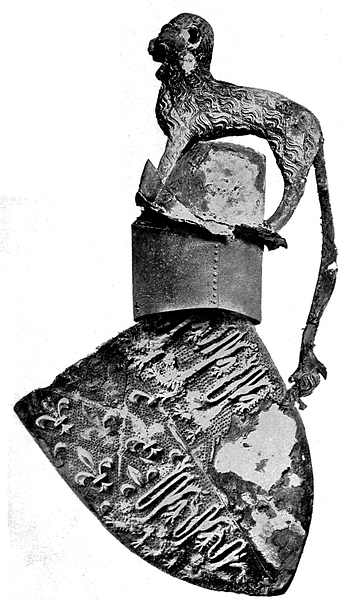

As so many of the French nobility were cut down and the army's leadership eliminated, so the superior numbers of French infantry became only academic, there was nobody left to command them. By nightfall, the result was already clear. King Edward had won the battle with around 300 casualties compared to the 14,000 fallen French, the massacre a result of the French having raised their banner, the Oriflamme, to give no quarter. Traditionally, 1,542 French knights met their deaths (some historians would put the figure as high as 4,000). The flower of France's nobility and that of its allies was eliminated, including King John of Bohemia (r. 1310-1346 CE), the King of Majorca, the Count of Blois, and Louis of Nevers, the Count of Flanders. King Philip, unseated from his horse twice, was lucky to escape the debacle. It was after the battle, at least according to legend, that Prince Edward adopted the emblem and motto of the fallen King of Bohemia - an ostrich feather and Ich Dien or 'I serve'. Over time the ostrich feathers became three, and they remain today the symbol of the Prince of Wales.

Aftermath

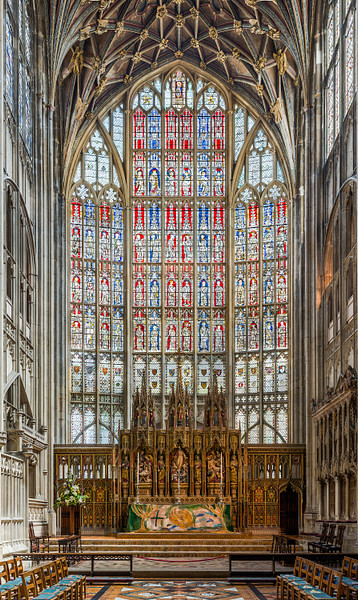

The victory at Crécy became the stuff of legend, with the cream of those knights who had fought there rewarded with membership of Edward III's new exclusive club: the Order of the Garter (c. 1348 CE), England's still most prestigious relic of medieval chivalry. The victory also signalled that, at last, England was no longer the inferior of France, a position it had endured ever since the Norman Conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066 CE. Another commemoration which survives today (or at least a partial one), is the so-called Crécy window of Gloucester Cathedral which shows many of the noble figures involved in the battle and their coats of arms.

Back on the medieval battlefield, in July 1347 CE, an English army captured Calais after a long siege. Meanwhile, David II of Scotland (r. 1329-1371 CE) and an ally of Philip VI, had invaded England in October 1346 CE. Durham was the target, but an English army defeated the Scots at the Battle of Neville's Cross on 17 October 1346 CE). King David was captured and Edward III now seemed unstoppable. A decade later, another great victory would come against the French at the Battle of Poitiers in September 1356 CE. This success was even more significant than Crécy because the king of France was captured.

After a period of peace from 1360 CE, the Hundred Years' War carried on as Charles V of France, aka Charles the Wise (r. 1364-1380 CE) proved much more capable than his predecessors and began to claw back the English territorial gains. By 1375 CE, the only lands left in France belonging to the English Crown were Calais and a thin slice of Gascony. During the reign of Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE) there was largely peace between the two nations, but under Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422 CE), the wars flared up again and witnessed the great English victory at the Battle of Agincourt in October 1415 CE. Henry was so successful that he was even nominated as the heir to the French king Charles VI of France (r. 1380-1422 CE). Henry V died before he could take up that position, and the arrival of Joan of Arc (1412-1431 CE) in 1429 CE saw the beginning of a dramatic rise in French fortunes as King Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461 CE) took the initiative. The weak rule of Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71 CE) saw a final English defeat as they lost all French territories except Calais at the wars' end in 1453 CE.