For the ancient Egyptians, life on earth was only one part of an eternal journey which continued after death. One's purpose in life was to live in balance with one's self, family, community, and the gods. Any occupation in Egypt was considered worthwhile as long as one was performing one's duties in accordance with harmony and balance.

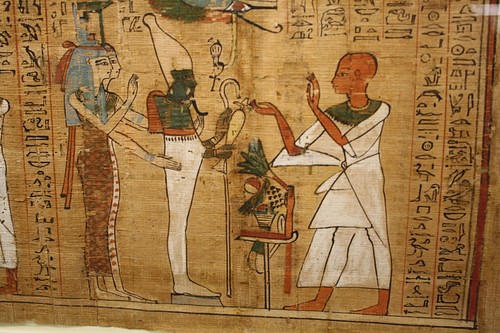

The concepts of harmony and balance were personified by the goddess Ma'at who presided over ma'at, the central value of Egyptian culture. This is evident through inscriptions as well as artwork depicting people engaged in various jobs presented, for the most part, admirably.

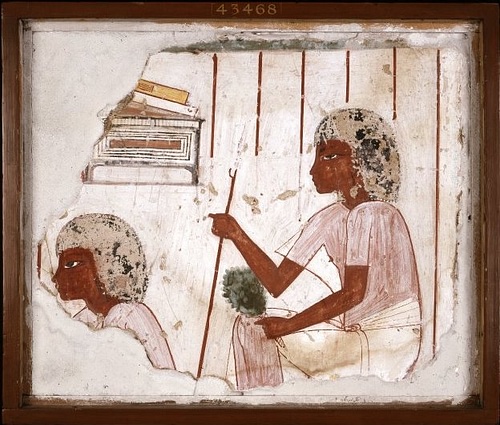

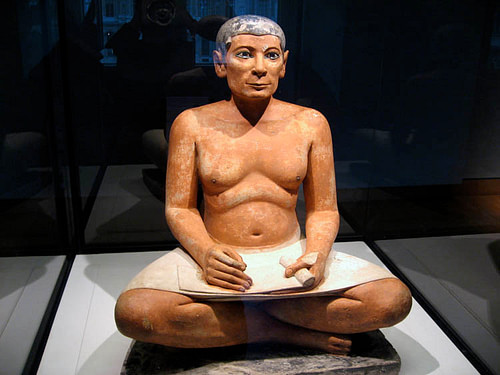

The inscriptions were set down by scribes, among the most highly respected professions in Egypt, and while most of their works have other people, professions, or events as subject matter, there are a number which celebrate the occupation of scribe above all others. The most famous of these is The Satire of the Trades (from the Middle Kingdom, 2040-1782 BCE) in which a father encourages his son to become a scribe because it is better than any other profession. Another well-known work, this one from the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE), is A Schoolbook or Be a Scribe which delivers the same message, this time from a teacher to a lazy student.

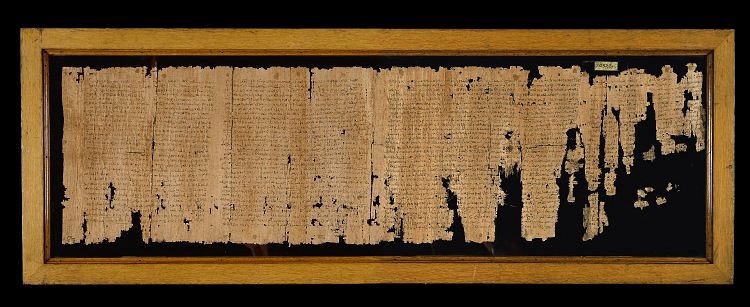

There is another work from the New Kingdom along these same lines which, in addition to listing the many earthly benefits of the scribal profession, make clear that it is the one sure path to eternal life: The Immortality of Writers (also known as The Endurance of Writing: A Eulogy to Dead Authors from Papyrus Chester Beatty IV (registered in the British Museum as number 10684, Verso 2,5-3,11). The poem makes clear that, even though everyone, no matter their occupation or social class, needed to be honored through remembrance after death, a scribe would be remembered, not only by family and friends, but by a much larger audience through the works they left behind.

Writing from the Gods

The craft of writing in ancient Egypt was not seen as simply a means of conveying information or keeping records nor was it thought of only as a means of entertainment or commemorating events. Writing was the act of creating reality, of bringing the unseen into the visible world, and establishing it as a truth.

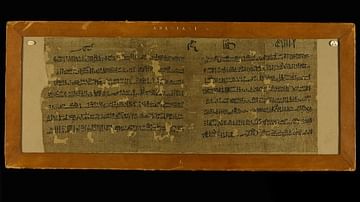

Inscriptions for the recently deceased such as the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE), the Coffin Texts (c.2134-2040 BCE), and The Egyptian Book of the Dead (c. 1550-1070 BCE) made the next life comprehensible to those who were about to embark on the journey through the afterlife but, on the practical earthly level, their vision of the next world became the reality of the ancient Egyptians. Throughout most of Egypt's ancient history (except for some notable exceptions in the literature of the Middle Kingdom), there is no marked fear of death because one knew what was coming when one died and knew this because of scribes.

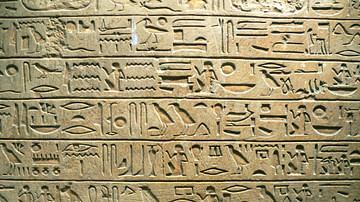

The great god Thoth was believed to have invented writing and gave it to humanity (although some myths claim it was given by his consort, the goddess Seshat, or by Isis, or another deity). Writing was considered sacred and the ancient Egyptians referred to their writing system as medu-netjer (“the gods' words”) which was translated by the Greeks as hieroglyphics (“sacred carvings”). Thoth was venerated by the people from the Predynastic Period (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) through the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE), the last era of ancient Egypt's history before it was taken by Rome.

Throughout this entire time, words carried the same power to create, sustain, heal, curse, and protect (as evidenced in magical spells given to humanity by the god Heka) and the written word was even more powerful because it endured. Many spells were no doubt memorized for quick recitation when needed but only those written are still known in the present day.

Scribes in ancient Egypt were mostly anonymous. They wrote as part of their duties in the Per-Ankh (“House of Life”), the scriptorium attached to a temple, or wrote for the king or a wealthy noble and only sometimes is the author's name attached to a manuscript. The writer's name did not need to be remembered for them to live eternally, however, because Seshat – goddess of books, libraries, and librarians (among other responsibilities) – would magically receive a copy of one's work to place in the library of the gods as soon as it was written.

In this way, one's work would continue to exist on earth as well as in the heavens and one's name, whether attached to a specific piece or not, would last as long as the work did. Since the piece was housed in the library of the gods as well as those on earth, the writer would live forever through that work.

Virtue & Writing

These writings had to be true in order to have any meaning or worth, but 'true' did not always equate with 'factual'. Works of literature like The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor (from the Middle Kingdom) or The Tale of Prince Setna (also known as Setna I from the Ptolemaic Period) are fiction but represent not only the truth of human existence as the writer saw it but important cultural values such as courage, trust, and loyalty to others and one's homeland.

The scribe was rewarded, not simply through payment for a work completed, but by the honor of creating something which did not exist before. In this, the scribe was linked to the great gods like Atum, Neith, and Heka, all represented as being present in the first act of creation when order was fashioned from the nothingness of chaos. The audience benefitted in being reminded of the culture's central values and their place in the universe, and this was just as true for popular works widely read or recited as inscriptions no living eyes would ever see after they were done.

Just because a text was written on the inside of a tomb to be sealed, it was not considered any less worthy than a grand piece like The Poem of Pentaur, inscribed in large writ on temple walls during the reign of Ramesses II (also known as The Great, r. 1279-1213 BCE) to immortalize his victory at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE. Scholar Rosalie David comments:

The essential purpose of writing was not decorative since texts were frequently inscribed in places within the tombs and on funerary goods where they would not be visible once the burial was sealed. Similarly, although the cursive forms of the script, known as Hieratic and Demotic, were widely used for secular and commercial purposes, the intrinsic value of writing was never ignored; the act of writing, regarded as a spiritual function, was always expected to benefit the scribe and the recipient of the text. (27)

In the case of tomb inscriptions, of course, it was understood that the text would in fact be 'seen' by the soul of the recently deceased who would need the inscription to recognize what had just happened to its body and what it needed to do next. In this way, the text was not only appreciated but actually vital to the soul's continuance on its eternal journey.

One could only hope to reach eternal life in the Field of Reeds if one had lived a virtuous life, if one's heart was lighter than the feather of the goddess Ma'at when weighed in the Hall of Truth by Osiris, but one needed texts like The Egyptian Book of the Dead to know how to get there. The importance of virtue, of living a virtuous life, is emphasized throughout the wisdom literature of the Middle Kingdom since one could not hope to pass through the Hall of Truth if one's heart was weighed down with sins and self-interest.

Listening to the words of the scribes – especially works in the genre of wisdom literature which provided advice on how best to live – and putting their words into action, was thought to encourage that much-needed lightness of heart and balance which would profit the individual in life and after death.

Virtue was also closely associated with the occupation of scribe. The scribe had to know the culture's deepest values in order to communicate them and so their efforts were doubly rewarded; their hearts would be light in knowing the will of the gods and keeping balance in all things and they would have also encouraged others to do the same through their work. Further, as noted, they would live on through that work. Scholar R. B. Parkinson comments:

Writing offers an escape from mutability. This is compatible with statements elsewhere in wisdom literature that virtue is the only means of endurance since writing, as the preserver of information, is synonymous with ancient wisdom, and wisdom is virtue. (148)

Egyptian literature of the Middle Kingdom sometimes expressed skepticism of the afterlife, and in some, like The Lay of the Harper, these works actually deny the concept of the Field of Reeds or any sort of immortality, expressing a cynicism which notes how even the grandest tombs and monuments will fall and the names of those who raised them will be forgotten. An answer to that cynicism, expressed in The Immortality of Writers, is that writing is more lasting than any tomb, temple, or monument and the writer is remembered long after any great pharaoh or general every time a work is read.

Writing & Immortality

This poem, from the Ramesside era of the New Kingdom (so-called because of the succession of pharaohs who took the throne-name Ramesses), celebrates the act of writing, the glory of past writers, and invites any would-be authors to devote themselves to the only occupation which guarantees immortality. Scholar and Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim notes:

Writings, says the scribe, bestow on their authors an afterlife more real and durable than that provided by the stone-hewn tomb; for men's bodies turn to dust and their tombs crumble. Here the skepticism concerning man's immortality, which first found expression in the Middle Kingdom Harper's Song from the Tomb of King Intef [The Lay of the Harper], reaches a remarkable climax. Where the Harper's Song had deplored the disappearance of tombs and the absence of solid knowledge about life after death, the Ramesside author found an answer: bodies decay but books last and they alone perpetuate the names of their authors. (176)

The poem actually expresses the same sort of cynicism as the Middle Kingdom pieces in disregarding the promise of eternal life with the gods and focusing on what an individual could do to ensure immortality through remembrance. The poet mentions ka-servants (also known as ka-priests) who were paid to remember and pay service to the soul (ka) of the deceased and notes how they, like the tombs themselves, will eventually be gone. Everything will pass away, the poet observes, except for the written word and the names of authors who have created memorable pieces.

The last stanza of the poem reminds a reader of the names of some of these authors, many of whom are known for writing instruction pieces, included today in the genre of wisdom literature of the Middle Kingdom, who live on through their works. R. B. Parkinson notes how “time has confirmed the scribe's claim and many of the sages' works survive still” (148). These names may not be familiar to a modern-day audience, but for the poet's time, their mention would be as effective as someone today referencing Malory, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Dante, Murasaki, or Hemingway.

The complete text of the poem follows as found in Lichtheim's Ancient Egyptian Literature: The New Kingdom:

If you but do this, you are versed in writings.

As to those learned scribes,

Of the time that came after the gods,

They who foretold the future,

Their names have become everlasting,

While they departed, having finished their lives,

And all their kin are forgotten.

They did not make for themselves tombs of copper,

With stelae of metal from heaven.

They knew not how to leave heirs,

Children [of theirs] to pronounce their names;

They made heirs for themselves of books,

Of Instructions they had composed.

They gave themselves [the scroll as lector-] priest,

The writing-board as loving son.

Instructions are their tombs,

The reed pen is their child,

The stone-surface their wife.

People great and small

Are given them as children,

For the scribe, he is their leader.

Their portals and mansions have crumbled,

Their ka-servants are [gone];

Their tombstones are covered with soil,

Their graves are forgotten.

Their name is pronounced over their books,

Which they made while they had being;

Good is the memory of their makers,

It is forever and all time!

Be a scribe, take it to heart,

That your name become as theirs.

Better is a book than a graven stela,

Than a solid tomb-enclosure.

They act as chapels and tombs

In the heart of him who speaks their name;

Surely useful in the graveyard

Is a name in people's mouth!

Man decays, his corpse is dust,

All his kin have perished;

But a book makes him remembered

Through the mouth of its reciter.

Better is a book than a well-built house,

Than tomb-chapels in the west;

Better than a solid mansion,

Than a stela in the temple!

Is there one here like Hardedef?

Is there another like Imhotep?

None of our kin is like Neferti,

Or Khety, the foremost among them.

I give you the name of Ptah-emdjehuty,

Of Khakheperre-sonb.

Is there another like Ptahhotep,

Or the equal of Kaires?

Those sages who foretold the future,

What came from their mouth occurred;

It is found as [their] pronouncement,

It is written in their books.

The children of others are given to them

To be heirs as their own children.

They hid their magic from the masses,

It is read in their Instructions.

Death made their names forgotten

But books made them remembered. (176-177)

Conclusion

The poet ends the piece with an echo of the theme of the first stanza on making one's name everlasting, neatly tying up the poem while driving home the central point. In the modern day, this argument may not seem so convincing when, after all, one is certainly more apt to think of the Great Pyramid or Karnak or the Nile River in hearing the name 'Egypt' than any ancient writings.

Even so, it must be remembered, the great monuments of Egypt today are in ruin and the Nile certainly looks quite different from how it did a mere twenty years ago. The works of the ancient Egyptian scribes, by contrast, are the same as they were over 3,000 years ago.

The point the poet makes is familiar to any student of literature in the present day, probably best expressed by Shakespeare in his Sonnet 18 (“Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day?”) which concludes with the couplet:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. (lines 13-14)

Here, Shakespeare is promising immortality to the subject of his poem but, as the author, is equally aware that he will also live as long as the poem is read. The poem is fixed, it will never change, and will never fall into ruin; precisely what the poet of the ancient Egyptian eulogy is claiming.

Even so, remembrance was dependent on how well one's work was received and the level of popularity it then enjoyed. Most people are at least aware of the novel The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway but almost no one has ever heard of The Professors Like Vodka, a novel by Harold Loeb, Hemingway's contemporary and the model for the character of Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises. In order to be remembered for one's work, the work had to resonate with an audience and be worthy of remembrance, and this is what the ancient Egyptian scribes meant in making a piece 'true'. A true piece would find an audience, and the writer would then live forever because of it.

The ancient Egyptian afterlife was easily the most comforting vision in antiquity, offering a virtual mirror-image of what one thought had been lost in death. Still, then as now, there was always some doubt as to how it would all work out once one had crossed into the realm no one returned from. Rather than wait to see how one's soul fared in judgment in the Hall of Truth, the scribes created an insurance policy for immortality while they lived, and as the poet says, their books have indeed made them immortal.