The World Heritage-listed Nazca lines are a well-known part of the ancient heritage of Peru. One woman spent over 50 years studying and protecting them. Ana Maria Cogorno Mendoza shares the story of Dr Maria Reiche.

The lines and geoglyphs of Nazca are one of the most impressive-looking archaeological areas in the world and an extraordinary example of the traditional and millenary magical-religious world of the ancient Pre-Hispanic societies. They are located in the desert plains of the basin river of Rio Grande de Nazca, the archaeological site covering an area of approximately 75,358.47 hectares.

For nearly 2,000 uninterrupted years, the region's ancient inhabitants drew thousands of large-scale zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures and lines on the arid ground - animals, birds, insects, other living creatures and flowers, plants and trees, as well as geometric shapes and miles of lines of deformed or fantastic figures. In 1939 CE they were rediscovered and a year later, Dr Maria Rieche, began a lifetime of study and protection of these remarkable sites.

The impressive story of the Pre-Hispanic culture in Peru dates back to before the arrival of the Spanish Conquest (1532 – 1572 CE). Over many centuries, ancient civilisations created a vast array of wonderful monuments all over Peru, but all of them had in common an astronomical connection. These cultures developed advanced techniques of agriculture, gold and silver work, pottery, metallurgy and weaving. Some of the social structures from the 12th century CE formed the basis of the later Inca Empire.

In the arid coastal plain, 400 km south of Lima, in the department of Ica, we find one of the oldest, most extraordinary civilisations: the Paracas culture. This culture flourished on the southern Pacific coast of the central Andes around 600 - 150 BCE and is one of the earliest known complex societies in Peru. The great Paracas Necropolis was discovered by archaeologist Dr Julio C Tello. In 1927 CE, he discovered 429 mummy bundles in Cerro Colorado in the Paracas Peninsula. In the vast communal burial site, he found these mummy bundles, each with their body in the foetal position and bound with cords. They were wrapped in many layers of wonderful woven textiles, considered some of the finest ever produced, and dated to around 300 - 200 BCE.

The Paracas Peninsula is a desert within the boundaries of the Paracas National Reservation, a marine reserve which extends south along the coast. The only marine reserve in Peru, it is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. This Protected Natural Area is considered one of the strangest and richest ecosystems in the world and is home to colonies of sea lions and thousands of resident and migratory sea birds, including pelicans, flamingos, boobies, cormorants, terns, gulls, and in summer, condors.

The Nazca Lines

One of the most sophisticated of the early Peruvian cultures is the pre-Hispanic Nazca civilisation, known for the carvings which they etched onto the surface of the ground between 400 BCE and 650 CE. The builders of these magic and mysterious lines and geoglyphs of Nazca and Palpa created a sacred place. The geoglyphs are one of the most unique and extraordinary artistic achievements, unrivalled in their diversity and dimensions, anywhere in the world. In the arid Peruvian coastal plains, 450 km south of Lima, in the high and arid plateau of the basin of Rio Grande, the area stretches 50 km between the towns of Palpa and Nazca.

The Nazca plain is unique in its preservation due to the combination of the climate, one of the driest in the world, with little rainfall each year, and the flat stony ground which minimises the effect of the wind at ground level. Beneath the desert's crust of pebbles, which contain ferrous oxide, is a lighter-coloured subsoil. The exposure over centuries has given the crust of pebbles a dark patina. When the dark gravel is removed, it contrasts with the paler-coloured soil underneath.

In this way, the lines were drawn as furrows of a lighter colour, even though in some cases they became prints. In other cases, the stones defining the lines and drawings form small lateral humps of different sizes. Some drawings, especially the early ones, were made by removing the stones and gravel from their contours and in this way the figures stood out in high relief. The concentration and juxtaposition of the lines and drawings leave no doubt that they required intensive long-term labour, as is demonstrated by the stylistic continuity of the designs, which clearly correspond to the different stages of cultural changes.

The images represent a remarkable manifestation of a common religion and social homogeneity that lasted a considerable period of time. They are the most outstanding group of geoglyphs anywhere in the world and are unmatched in their extent, magnitude, quantity, size, diversity and ancient tradition. The concentration and juxtaposition of the lines, as well as their cultural continuity, demonstrate that this was an important and long-lasting activity, lasting approximately 1,000 years.

Apart from the anthropomorphic figures, the lines, which are generally straight lines, criss-cross certain parts of the pampas in all directions. Some are several kilometres in length and form designs of many different geometrical figures, triangles, spirals, rectangles and wavy lines. Others radiate from a central promontory or encircle it. Another group consists of so-called '"tracks", which appear to have been laid out to accommodate large numbers of people.

This unique and magnificent artistic achievement of the Andean culture is unrivalled in its extension, dimensions and diversity and long existence anywhere in the prehistoric world. The designs are laid out with outstanding geometric precision, transforming the vast land into the highly symbolic, ritualistic and social-cultural landscape that remains to this day.

Quite apart from the geometric shapes and several zoomorphic designs, what it is amazing is the abstract conception of the designs, which demonstrate a perfect harmony. The inspiration of their work suggests they may have been ritual offerings to a goddess, which even now relates to extraordinary natural celestial events.

One of the best known of the prehistoric geoglyphs, called El Candelabro (the Trident), is 600 feet tall and can be seen from twelve miles out to sea. It is on the slope of a hill facing the ocean and was created by the Paracas people by removing the top layer to reveal the lighter layer underneath in low relief. This geoglyph is related to the geoglyphs, lines and figures of Nazca. When archaeologist Dr Maria Reiche was measuring the geoglyphs she found pieces of broken pottery belonging to the Paracas people on the site. Although the exact age of the design is still unknown, Dr Reiche analysed the broken pottery through carbon dating to around 200 BCE.

What is interesting is that the design looks out towards the ocean from the hillside. It is amazing to see how the Paracas people observed where to place the figure for good natural conservation, with the salt of the sea breeze, the sun and the strong wind making a perfect crust of layers to create a patina over hundreds of years.

The wise men of the Paracas culture, fathers of the Nazca people, were great astronomers. They observed celestial events and realised the importance of time, nature, and cosmos. Almost all their temples were near the ocean, mountains, rivers, hills and valleys, which were considered sacred and alive. Their philosophy was for a peaceful way of life. El Candelabro has a special appearance when rain has fallen, as the patina of salt which naturally conserves the figure can be seen.

The system of lines and geoglyphs, which has survived intact for more than two millennia, evidences an unusual way of using the land and the natural environment that represents a highly symbolic cultural landscape. The construction technology allowed them to design large-scale figures with outstanding geometric precision. Set in their surrounding landscape they create a harmonious relationship that has survived virtually unaltered over the centuries.

The authenticity of the lines and geoglyphs of Nazca is indisputable. The method of their formation, by removing the overlying weathered gravels to reveal the lighter bedrock, is such that their authenticity is assured. The creation, design, morphology, size and variety of the geoglyphs and lines correspond to the original designs produced during the historical evolution of the regions and have remained unchanged. The ideology, symbolism and sacred and ritual character of the geoglyphs and the landscape are clearly represented, and their significance remains intact even today.

Dr Maria Reiche

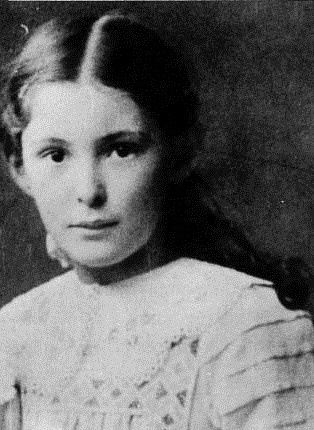

Dr Maria Reiche was born on May 15, 1903 CE in Dresden, Germany, where she graduated in Mathematics, Geography and Astronomy, as well as speaking five languages. In 1932 CE she arrived in Peru to work in Cusco city as a teacher to the sons of the German Consulate, where she lived for three years.

Her first astronomical investigation was at Machu Picchu in the Intihuatana temple. The notable ritual stone related to an astronomical clock or calendar; it was aligned with the sun's position during the winter solstice. She carried out more important astronomical research near Lima, perhaps one of the most important contributions to archaeology, relating to the astronomical positions of the religious temple. Established in 200 CE, the temple's main power lay in its deity Pachacamac, the 'Earth Maker' creator god, who made the earth tremble and brought life to everything in the universe.

It was not until the 20th century CE, however, that the Nazca lines drawn in the sand were actually discovered. Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejía Xesspe first saw the lines in 1927 CE after finding them almost by accident, since they are practically invisible at the surface. He assumed that they were “sacred pathways”.

In 1939 CE, Paul Kosok, an American professor in History at Long Island University in New York and the main expert on irrigation systems of ancient cultures of the world, came to Peru. He was interested in the irrigation system in the Nazca region and became the first scholar to explore the lines in depth. The following year, he introduced Maria Reiche to the site and a new hypothesis soon developed. They happened to be standing near one of the long straight lines at sunset when they both made a discovery that would change their lives.

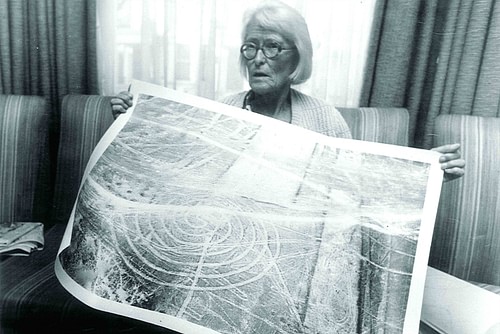

This happened on June 21, 1939 CE, the southern hemisphere's shortest day of the year. Kosok and Reiche noticed that the sun was setting almost exactly over the end of one of the Nazca Lines, so it appeared to be a solstice line. Pronouncing the lines “the largest astronomy book in the world”, Kosok then took aerial photographs in order to get a complete overview. The following December, on the summer solstice, Reiche also found such lines and, captivated by the landscape and the scope of Kosok's project, found her own life changed forever.

With their new information, Reiche and Kosok quickly refuted the “sacred pathways” hypothesis. In Reiche's view, which has changed little over the decades, the lines represented a gigantic astronomical calendar recording the passage of the seasons and predicting solar and lunar eclipses. The lines plot the directions of the stars: for example, the spider (150 feet long) is associated with the constellation of Orion, as is the monkey with the Pleiades. The latter, covering over 300 feet, was Reiche's favourite figure and, like Reiche herself (who lost a finger at Cuzco), displays only four fingers on one hand, a divine characteristic that is found in other drawings as well.

The Nazca people were able to become a part of the grand astronomical design, observing the movements of heavenly bodies and learning exactly when to begin planting and when to harvest', Reiche said.

Reiche also associated the enormous figure of the monkey with the Big Dipper constellation by uncovering lines connected to the figure that indicates the position of this constellation's largest star. The monkey could also be considered a god of water since the appearance of the Big Dipper announces the arrival of the rainy season.

After Kosok left in 1948 CE, she continued the work and mapped the entire area and determined there were 18 different kinds of animals and birds. She also discovered how the Nazca solved calculus problems in order to trace perfectly proportioned figures on a gigantic scale. Not only did they employ charts to measure small distances and then multiply them by using stakes and long cords in the manner of giant compasses, but they also knew how to measure angles. In other words, they understood the principles of geometry.

Because the lines can be seen best from above, she persuaded the Peruvian Air Force to help her make aerial photographic surveys. Reiche devoted her life to saving this archaeological site which is unique in the world. She worked alone from her home in Nazca and funded all her research herself, only helped financially by her sister, Dr Renata Reiche.

In 1949 CE she published her theories in the book The Mystery on the Desert (reprinted in 1968 CE) and used the profits from the book to campaign for the preservation of the Nazca desert and to hire guards to protect the Lines. The Pan American Highway, a government development, cut into some of the pictographs, especially the longest, a lizard measuring over 600 feet and so she spent a lot of money lobbying the government and educating the public about the lines. After paying for private security to protect the geoglyphs, she finally convinced the government to restrict public access to the area but provided towers near the highway so that visitors could have an overview of the lines to appreciate them without damaging them.

Many scholars have followed her investigations but it is through her lonely struggles against destruction and her passion for preservation that the Nazca lines and geoglyphs have been conserved for a new generation.

Now the lines and geoglyphs of Nazca, with their protection area that extends over 75,358.47 ha, are well defined and, together with their surrounding landscape, make a harmonious relationship that has survived virtually unaltered over the centuries.

Reiche spent almost 60 years of her life in the pampas. Still remembered well in the town of Nazca for regaling locals and visitors with her magnetic storytelling, she is also revered for her unceasing life's work, which included cleaning the contours of almost 1,000 lines with ladder and broom. She has also defied those who wanted to convert the area into an immense agricultural operation. Her studies (collected in 60 notebooks) are illuminated by her conservationist zeal. Her contributions to the geometry and astronomy of ancient Peru were published in 1993 CE when she was 90 years old.

Maria Reiche died on June 8, 1998 CE, at the age of 95. She had devoted more than half her life to the measuring and mapping of the lines. Her intensive work for so many years was also costly to her health as exposure to the bright sun eventually caused her to go blind. During her lifetime she received much acknowledgement and numerous honours from all over the world and inspired many new generations of scientists with her passion for preserving the Nazca Lines.

One of her greatest achievements was the nomination of the lines and geoglyphs of Nazca and Palpa World Cultural Heritage as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995 CE, and her great efforts in the protection and maintenance work of the site became the responsibility of the Peruvian Government.