The term Agora (pronounced ah-go-RAH) is Greek for 'open place of assembly' and, early in the history of Greece, designated the area in a city where free-born citizens could gather to hear civic announcements, muster for military campaigns, or discuss politics. It later designated the open-air marketplace of a city.

The agora of Athens is the best-known, though the term was used in other city-states for their public spaces where events of the day were discussed, merchants had their shops, and craftspeople sold their wares. Agora is therefore also understood to mean an assembly of people as well as where they meet. The agora of Athens was located below the Acropolis near the building which today is known as the Theseion (the Temple of Hephaestus), and open-air markets are still held in that same location today. The site is frequently referenced as the birthplace of democracy since it was here that political discussions and arguments gave rise to that concept.

The site was destroyed, along with the rest of the city, during the Persian king Xerxes’ invasion in 480 BCE and was rebuilt by order of the Athenian statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE). Socrates (l. c. 470/469-399 BCE) questioned the citizenry of Athens in the agora, and it was there that the young playwright and aristocrat Aristocles of Athens first heard him speak, burned his plays, and devoted himself to the development of Greek philosophy under the name Plato (l. 428/427 - 348/347 BCE). The agora was also the site of the court which condemned Socrates for impiety in 399 BCE and sentenced him to death.

The agora was important because it was where the community congregated to discuss events of the day, politics, religion, philosophy, and legal matters. The agora served the same purpose in ancient Athens as the town square and town hall in later societies. Like the later town centers, the agora was a cultivated area adorned with trees, gardens, fountains, colonnaded buildings, statues, monuments, and shops selling assorted goods.

The Athenian agora played host to later philosophers after Socrates such as Diogenes of Sinope (l. c. 404-323 BCE) who actually lived there on the streets, Crates of Thebes (l. c. 360-280 BCE) and his wife Hipparchia of Maroneia (l. c. 350-280 BCE), who did the same, and Saint Paul (l. c. 5 - c. 64 CE), who preached there at the Areopagus. According to the biblical Book of Acts 17:16-33, Paul encountered the Stoics and the Epicureans at the Athenian agora and preached the news of the gospel of Jesus Christ to them there.

The agora continued as an important site of commerce, public discourse, and social life through the early Roman period but was destroyed in 267 CE by the Germanic Heruli and in 396 CE by the Visigoths. In the 7th century CE, some buildings – like the Temple of Hephaestus – were converted into churches and so preserved. The site was officially recognized for its historical importance in the 19th century, and restoration of parts of it began in the 20th, notably the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos which today houses a museum. In the present day, the area around the ancient agora of Athens continues to serve as a meeting place for public discourse, commerce, and protest just as it did in the past and efforts have been made to preserve it as an important historic site.

Early Site & Development

The area of the agora was in use in the Neolithic Period as evidenced by archaeological finds including tools. In time, the area came to be used as a burial ground, and this usage was developed further during the period of the Mycenaean civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE). The Mycenaeans established themselves at Athens by c. 1400 BCE, constructing a large fortress on the Acropolis overlooking the area which would become the agora.

The fortress most likely served as the palace for the Mycenaean ruler and, in keeping with the tradition earlier established elsewhere, religious and funerary sites were located close to the palace, in this case, the area below the Acropolis. The Mycenaeans are well-known for their monumental tholos tombs and over 50 of these have been excavated at the agora site.

The Mycenaean Civilization declined around 1100 BCE (perhaps due to natural causes such as climate change or invasions from groups such as the Sea Peoples) during the period known as the Bronze Age Collapse but would be immortalized in literature. The heroes of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (8th century BCE) such as Achilles, Agamemnon, Ajax, Menelaus, and Odysseus, were all Mycenaean Greeks. The association of the “golden age” of the Mycenaeans with Athens was celebrated by the writer Hesiod (8th century BCE), giving the city generally, and the area around the acropolis specifically, an elevated status.

Agora & Democracy

By the 6th century BCE, the agora was already a residential district with homes built around what would become the marketplace. Residences encouraged the construction of public buildings and manufacturing sites, and the area developed through trade as it was easily accessible from the surrounding farmlands as well as the seaport of Piraeus. The only actual road in Greece (not a goat path) in the early 6th century BCE was The Sacred Way, the route from Athens to the city of Eleusis used by participants in the ritual of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The other “roads” to and from the area of the agora were footpaths made by merchants and animals.

Written laws were first instituted by the statesman Draco (l. 7th century BCE), but these were considered harsh and restrictive and so were reformed by the lawgiver and statesman Solon (l. c. 630 - c. 560 BCE) c. 594 BCE who broke the hold of the upper class on political participation and opened it to all Athenian citizens. He divided the citizenry into four classes based on their income from property. The Areopagus, which had formerly been the meeting place of the upper-class Archons, was now open for political discussions by any male citizen of Athens.

In 565 BCE, the populist tyrant Peisistratus (d. c. 528 BCE), a relative of Solon’s, seized control of the Athenian government in a coup, putting an end to this early version of democracy. His control was continued by his sons Hipparchus and Hippias until c. 510 BCE when Hippias was overthrown by the Athenians with help from Sparta. Under Hippias, a number of significant building projects were initiated or continued. Peisistratus had decreed many during his reign, including the Panathenaic Way.

The Panathenaic Way, a street leading from Athens’ Dipylon Gate up to the Acropolis, was the route used during the Panathenaic Festival (c. 566 BCE - 3rd century CE), honoring the goddess Athena, and entered the agora at the northwest corner, exited at the southeast, and went up to the temples on the Acropolis. Hippias remodeled the area of the road’s entrance to the agora and ordered construction of the Temple of Zeus in the area.

After Hippias was overthrown, the Athenians rewrote their recent history, omitting the vital role Sparta had played, and credited the coup to two young men – Harmodios and Aristogeiton – who had really had nothing whatsoever to do with it. The two had assassinated Hipparchus in 514 BCE over a personal insult, not to topple the regime, but were hailed as liberators. Bronze statues of "the tyrannicides" were placed in the agora – "the earliest political monument in Europe" – according to scholar Robin Waterfield (58), and they were so highly regarded that, when they were later removed by the Persians in 480 BCE, they were immediately replaced.

In this atmosphere of liberation following Hippias’ fall, the statesman Cleisthenes (l. 6th century BCE) reformed the laws of Solon and established democracy in Athens. Democracy already existed in varied forms elsewhere, but Athenian democracy would become the model for later governments, giving it the prestigious place it has in history and honoring Cleisthenes with the title "Father of Athenian Democracy" which, in the present day, is usually understood as modern democracy even though it is not.

Only male citizens were allowed to vote, and there were other stipulations making Athenian democracy quite different from the modern concept. Even so, Cleisthenes’ reforms established the model which was improved upon by later Athenian statesmen and then by other governments elsewhere, and this initial experiment in government began in the agora. Scholar Thomas Cahill comments:

To us, looking backwards, it may seem imprudent to invite all citizens to vote on all major initiatives, but Solon was right to appreciate that no Athenian freeman could allow himself to be left out of anything. The continual buzz of conversation, the orotund sounds of the orators, the shrill shouts from the symposia – this steady drumbeat of opinion, controversy, and conflict could everywhere be heard. The agora (marketplace) was not just a daily display of fish and farm goods; it was an everyday market of ideas, the place citizens used as if it were their daily newspaper, complete with salacious headlines, breaking news, columns, and editorials. (118)

The agora became the center of political and social life in the 6th century BCE and developed accordingly. The main area became the marketplace surrounded by public and municipal buildings and carefully beautified with fountains, parks, trees, and statuary. All of this would be destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BCE.

Persian Invasion & Restoration

In 480 BCE, the Persian king Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) invaded Greece on a campaign of conquest. The Spartan king and general Leonidas (r. c. 490-480 BCE) held the Persians at the Battle of Thermopylae but, when he was defeated and killed, Xerxes I’s army marched on Athens and burned it. The agora was left in ruins and the statuary that was not destroyed was taken back to Persia. After the Persians were defeated in 479 BCE, restoration efforts began under the direction of Pericles.

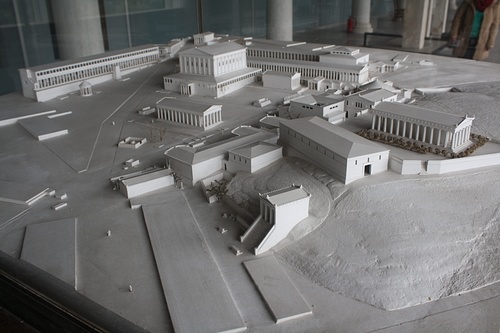

Pericles ordered the Panathenaic Way restored as well as the buildings surrounding its entrance to the agora on the northwest corner and its exit toward the Acropolis toward the southeast. Three stoas were constructed (or rebuilt) at this time – the Poikile Stoa, Southern Stoa, and Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios. The Temple of Hephaestus was also built at this time, and the city’s mint, the law courts, and shrines all restored and renovated. Among the shrines was the famous Altar of the Twelve Gods from which all distances in Athens were measured. The tholos tombs of the earlier Mycenaeans were also repaired and restored at this time as well as many other monuments and buildings of the district.

After Pericles’ restoration, the agora became the center of Athenian life once more. While work on the agora was ongoing, Pericles ordered the construction of temples on the Acropolis, including, of course, the Parthenon, dedicated to Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin), the patron deity of the city. The great sculptor Phidias (l. c. 480 - c. 430 BCE) created the statue of Athena for the temple and the painter Polygnotus (l. 5th century BCE) decorated it with his work.

The Greek tragedy playwrights Aeschylus (l. c. 525 - c. 456 BCE), Sophocles (l. c. 496 - c. 406 BCE), and Euripides (l. c. 484 - 407 BCE), and Greek comedy playwright Aristophanes (l. c. 460 - c. 380 BCE) all produced the first staging of their plays in and around the agora of Athens. The great sophist Protagoras (l c. 485 - c. 415 BCE) argued cases in the law courts there and taught in the public buildings. Philosophers such as Parmenides of Elea (l. c. 485 BCE), Zeno of Elea (l. c. 465 BCE), Anaxagoras (l. c. 500 - c. 428 BCE), and others all visited the agora and shared their visions with audiences.

Socrates regularly held court in the agora, questioning the people on their values and establishing the type of inquiry that lay the foundation for Western philosophy as developed by his student Plato. The agora during this period was the center of intellectual, artistic, cultural, religious, and political activity, and this legacy was honored by building projects at the time as well as those commissioned later.

Significant Buildings

There are many significant buildings whose ruins are still extant at the site of the ancient agora. These were mainly built (or rebuilt) with funds donated by wealthy benefactors. Among the most interesting are the following:

The Prytaneum – also known as the Tholos, the seat of government where the Council of Citizens would meet and where the sacred fire was kept burning that symbolized the life of the community. Heroes of the Olympic games and military victories were honored here, and it was located near the center of the agora. Seventeen executives would remain at the Tholos/Prytaneum to deal with any unexpected emergencies in the city and so it came to be closely associated with Athenian democracy in its response to the peoples’ needs.

Poikile Stoa - (also known as the Stoa Poikile, Painted Stoa, and Painted Porch) built with funds donated by the brother-in-law of the statesman Cimon of Athens (l. c. 510-450 BCE). This building became one of the most famous in all of Greece for the paintings in it depicting various military victories, especially the Battle of Marathon of 490 BCE.

The Stoa of Attalos – built as a gift by King Attalos II of Pergamon (r. 159-138 BCE). It was destroyed by the invading Germanic tribe of the Heruli in 267 CE and what was left was further damaged in 396 CE by the Visigoths. The building was completely restored in the 1950s and today houses the Museum of the Ancient Agora.

Agoraios Kolonos – ("hill of the Agora") – built near the Temple of Hephaestus, and once the hall of assembly of the craftspeople of the agora, this building is thought to have also served as a manufacturing center. Two cistern systems served this building, their ruins still extant, suggesting that the structure – or at least the site – was used in the production of crafts which required access to water.

The Temple of Hephaestus – Built between c. 450-415 BCE and dedicated to the god Hephaestus, patron of craftspeople. In the modern day it is frequently referred to as the Thesion because it was once thought to have been built to house the remains of Theseus, the legendary founder of Athens. The Thesion is the site of outdoor markets on festival days and weekends today, continuing the tradition of the ancient agora.

Conclusion

Rome took Greece as a province in 31 BCE after the Battle of Actium and held it until 1453 CE when it was taken by the Ottoman Empire. During that time, the agora developed further with structures such as the Odeon of Agrippa added and many more statues adorning parks and residences. The Roman emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE) erected a number of statues throughout the agora and contributed to its development in other ways throughout his reign.

Paul the Apostle is thought to have preached to the Epicurean and Stoic philosophers at the assembly point known as the Areopagus ("Hill of Ares") c. 52 CE and after Christianity was embraced by the Greeks, a number of churches and Christian shrines were erected. The Church of the Apostles was built c. 1000 CE, and sometime around the 7th century CE, the Temple of Hephaestus was turned into a church.

The agora continued as the center of Athenian community and commerce under the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire, 330-1453 CE) and then under the Ottoman Empire after 1453: the fall of Constantinople. When the Greeks rebelled against Turkish rule in the 19th century, the agora was damaged in the fighting, as was the Acropolis. By c. 1831, restoration of the area had led to a number of residences and modern buildings erected at the site of the ancient agora on top of older structures and so the remaining area was declared off limits for urban development and declared an important historical site.

In 1832, the Temple of Hephaestus became the home of the first archaeological museum in Greece. Since that time, excavations at the site of the ancient agora have been ongoing and its historical importance more fully recognized. The Monastiraki shopping district and Monastiraki Metro Station, both located at the site of the agora, have taken measures to preserve the ancient site. The metro station features exhibits of artifacts excavated while the stores of the area have installed glass floors through which the ruins of the ancient site can be seen and appreciated by people in the modern era.