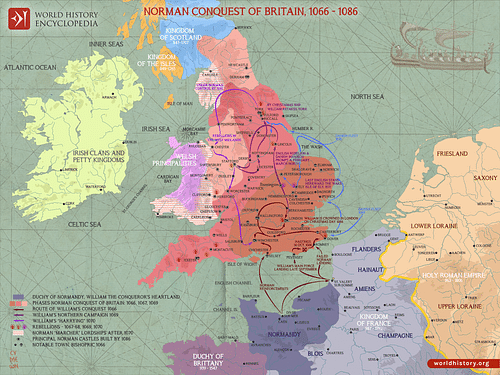

By the end of 1066 CE William the Conqueror had won a decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings, subdued the south-east of England and been crowned King William I in Westminster Abbey but there remained rebellion in the air throughout 1067 and 1068 CE. This was especially so in the north of England, where York was repeatedly the focus of anti-Norman forces, and which required the Norman king to 'harry' that region, that is to conduct a sustained campaign of attacks on crops, livestock, and villages throughout the winter of 1069-70 CE.

Hastings & the March to London

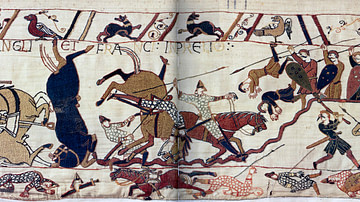

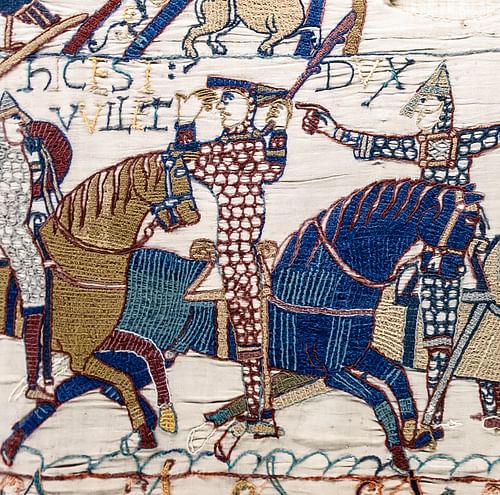

William, Duke of Normandy, invaded England in 1066 CE and defeated Harold Godwinson, aka Harold II (r. Jan-Oct 1066 CE) on 14 October at the Battle of Hastings. Over the next two months, William's army marched around south-east England winning control by force, intimidation or submission of such key strategic points as Dover Castle, Canterbury, Winchester and, finally, London. William was crowned king on Christmas Day of the same year but his new kingdom was far from secure. Still, it had been a hard campaign, motte and bailey castles had been built to protect his gains, and now some rest and recuperation were needed. The new king had at least received oaths of loyalty from Stigand, the archbishop of Canterbury, and most of the Anglo-Saxon nobles. William gave lands to his followers in return for their promise to perform military service to protect the kingdom, although this did not always go to plan, as with the murder of Copsi, the new Earl of Northumbria, murdered by a relation of his Anglo-Saxon predecessor. There would also be some trouble in Hereford where Eadric the Wild attacked the castle there, helped by the Welsh prince Bleddyn of Gwynedd. It seemed the Normans would be inheriting the problems the English kings had long been having with their frontiers.

William's army of several thousand men was simply not big enough to impose Norman rule everywhere and so a war of attrition developed with the Normans torching any towns and villages where resistance was prevalent. Forts and motte and bailey castles were erected in an attempt to discourage further armed resistance, Norwich receiving a new castle in early 1067 CE, for example. For the time being, though, William had established a strong enough footing in his new territory that he could even afford a return trip back to Normandy in March 1067 CE. Trusted nobles such as Odo of Bayeux (made the new Earl of Kent) and William Fitzosbern (made Earl of Hereford and who built a castle at Arundel in Sussex) were left to guard the kingdom. In Normandy, where William celebrated his English victories in the abbey of Fécamp and paraded a few high-ranking Anglo-Saxon 'hostages' for the amusement of his compatriots, the Conqueror basked in his well-deserved adulation.

Anglo-Saxon Rebellions: Exeter

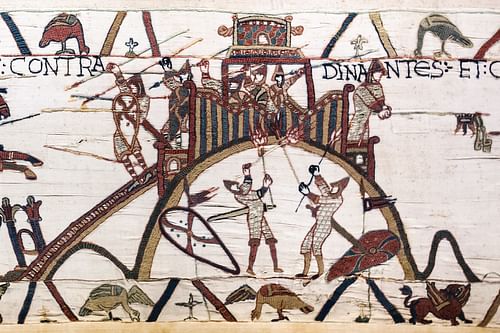

While William was absent, trouble was brewing in England. The honeymoon period when the Anglo-Saxon hierarchy seemed too shocked to effectively respond to the events of 1066 CE was coming to an end. There was even treachery amongst William's own allies, with Eustace of Boulogne attacking Dover - unsuccessfully - with a force from northern France in the autumn of 1067 CE, probably motivated by a dissatisfaction with the rewards he had received for fighting alongside William at Hastings. Then there was one of the first serious outbreaks of homegrown trouble at Exeter. A major cause of discontent was the heavy tax William had introduced, and because Exeter was also thought to be sheltering Gytha, the mother of Harold II, William felt compelled to return to England and deal with the trouble personally. Arriving on 6 December 1067 CE, William led an army to lay siege to Exeter, then a well-fortified city.

Exeter was besieged for 18 days, William's men regularly attacking the city's outer walls and working to undermine them. Eventually, after heavy losses on both sides, the city surrendered in January 1068 CE and a new castle was built there to deter any future trouble. The rest of the western corner of England was similarly subdued. William was now confident of his control of all of southern England, and by Easter, he was back at Winchester. On 11 May William's wife, Mathilda was crowned queen in Westminster Abbey with what was left of the Anglo-Saxon nobility in respectful attendance. Still, though, the volatile north remained to be dealt with.

Harold's Sons Attack Bristol

Before William could turn his attention to the north of England, circumstances intervened to present him with a more immediate problem. Harold Godwinson's son Godwine (and perhaps two of his brothers) launched an attack from Ireland in the early summer of 1068 CE. Godwine, whose mother was Harold's longtime lover Edith Swan-Neck, was likely in his teens but the family was obviously still wealthy enough to fund an army. The fleet, a mix of rebels and pirates, attacked the western coast of England at Avonmouth and then moved to take Bristol. The city resisted, and a local shire army was mustered, which successfully saw off the Godwinsons who fled back to Ireland to rethink their strategy.

The First Rebellion at York

Also in the summer of 1068 CE, the simmering discontent in the north broke out into what would be the first of three rebellions at York, the key city of northern England. William responded to the situation by marching northwards via Warwick and Nottingham. At Warwick, a large castle was built and a garrison established to keep an eye on Eadwine, earl of Mercia and one of most powerful Anglo-Saxon nobles. Nottingham got the same treatment as William progressed up the country ensuring his rear would not be challenged when he came to focus on York.

The northern rebels were organising themselves into an effective force, rallying around the figurehead of Edgar aetheling, great-nephew of Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE), but still only a teenager. Further, they had the support and sanctuary of the king of the Scots, Malcolm III (r. 1058-1093 CE), who had married Edgar's sister Margaret. Not only did the rebels want to reinstate what they considered the true line of kings in England - indeed, they were already calling Edgar their king - but many of the Anglo-Saxon barons who had lost their lands to Norman nobles (William alone had claimed around one-fifth of England for himself) found they had a great deal worth fighting for and not much to lose.

In the event, when the Conqueror arrived, the citizens of York were no doubt aware of the ruthless devastation caused by the king's army as it had marched north and they promptly swore their loyalty. Edgar and the rebel leaders fled to Scotland, although they would keep returning south over the next two years whenever a rebellion looked promising. To be doubly sure the city remained loyal, William took hostages and built yet another castle (this would become the famous Clifford's Tower which still stands - albeit leaning a little - today). William's loyal follower William Malet was made sheriff of the city and a new earl of Northumbria was installed, the Norman Robert de Commines. Returning to London, William stopped off to organise more castle-building at Lincoln, Huntingdon, and Cambridge.

Everything now seemed to be settling into place, and the new Norman order looked firmly and safely established. Then trouble started all over again in December 1068 CE and, once more, it was in the north. Robert de Commines arrived at his new post at Durham with a large force of knights (at least 500 by tradition) but rather than help keep the peace these warriors achieved the opposite by being rather too keen to plunder their new home. Northumbrian rebels then attacked Durham in January 1069 CE, killing any foreigners they came across, including the earl and wiping out his army. Even worse for the king, the rebellion quickly spread to York where the garrison commander was killed. William, just back from Normandy at the time, received news of the disasters at Durham and York and responded in typical fashion, personally force-marching north with an even bigger army than previously. William arrived in York so quickly he caught the rebels off guard and routed those still with a stomach to fight.

The Danish Invasion

In what must have seemed to William a never-ending story of recurring bad characters, Godwine then turned up again in the summer of 1069 CE, once more sailing from Ireland but this time with a more impressive fleet of around 60 ships. The former prince seemed intent on attacking the abbey of Tavistock in the southwest corner of England. Fortunately for William, the Count Brian of Brittany was on hand to deal with this new threat and the rebels were routed, Godwine fleeing back to Ireland for the third time, never to appear in the historical record again. There were also problems in Exeter and at Montacute Castle in the summer of 1069 CE as well as an attack on both Chester and Shrewsbury by Eadric the Wild. The revolts were all ruthlessly put down by loyal troops and local commanders but the kingdom was stubbornly refusing to be subdued and, even worse, a new character was about to make his appearance in the drama, Asbjorn, brother of King Sweyn II of Denmark (r. 1047-1076 CE).

The Danes had long claimed parts of England as their own, and these Viking warriors were infamous for taking full advantage of any political upheaval in foreign parts they considered a rich source of plunder. Asbjorn landed off the coast of northern England with a Danish fleet of some 300 ships in September 1069 CE, and Edgar was recalled from Scotland. York was, yet again, to be the focal point of the rebellion. Still in control of the city's castles, the Norman garrison did not do posterity any favours when they accidentally started a fire which spread out of control and partially burnt down the cathedral on 19 September. On 21 September, the Danes arrived and, joining forces with Anglo-Saxon rebels, the castles of York were taken, the commanders ransomed off and the ordinary troops massacred. This was the biggest Norman defeat of the entire conquest and now the most serious threat to William's reign in England.

From the Forest of Dean near Chepstow where he had been hunting, William assembled an army and marched, for the third time in two years, to York. Delayed at the River Aire by heavy rains and the resulting floods, when the king finally arrived at his destination, it was all rather disappointing. The rebels had fled the city, and the Danes had retreated down the River Trent with their extensive booty from York. Without a fleet of his own, William could not pursue the Danes and so he returned to the old policy of the Anglo-Saxon kings and paid them to leave English shores. To make it clear to anyone with an interest in the north of England, William decided to spend Christmas of 1069 CE in York, even moving the royal regalia there in a bold statement of intent.

The Harrying of the North

Any lingering rebels across the north of England were mercilessly hunted down and executed or mutilated over the winter of 1069-1070 CE. To ensure the local population also got the message that William was here to stay, vast swathes of northern England - from Chester and Shrewsbury in the west across to the northeast coast of Cleveland - were ravaged. This harrying was not a particularly controversial strategy of the period but it was a brutal one. Livestock, crops, and farming equipment were all burned so that no future rebel army would be able to support itself in the north. As the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle succinctly puts it, William "utterly ravaged and laid waste that shire [York]" (quoted in Allen Brown, 74). The consequence for ordinary folk was famine. An early 12th-century CE chronicle by Orderic Vitalis (a monk at the abbey of St Evroul in Normandy) puts the death toll caused by food shortages at 100,000 men, women, and children. Vitalis summarises William's ruthless strategy as follows:

He cut down many in his vengeance; destroyed the lairs of others; harried the land and burned homes to ashes. Nowhere else had William shown such cruelty. Shamefully he succumbed to this vice, for he made no effort to restrain his fury and punished the innocent along with the guilty. In his anger he commanded that all crops and herds, chattels and food of every kind should be brought together and burned to ashes with consuming fire, so that the whole region north of the Humber be stripped of sustenance.

(quoted in Bennett, 52-3)

While anti-Norman sources perhaps exaggerate the severity of William's harrying, the hardships seem self-evident, with people forced into eating whatever they could - from dogs to human corpses - and many even selling themselves into slavery in order to survive. The most telling statistic of all relating to the harrying of the north is perhaps a silent one, for in the 1086-7 CE Domesday Book, that carefully compiled and comprehensive record of land assets and property in Norman England, many entries describe northern areas of England merely as 'a waste' and Northumberland was not even worth recording at all.

Hereward the Wake & King Sweyn II

The subjugation of England was not quite finished yet. The Danes, although paid to leave the stage the year before, remained greedy for more booty in a kingdom that looked so unsettled. This time King Sweyn himself led the raiding party which attacked Ely in May 1070 CE. The abbey at Ely was a rallying point for Norman resistance, and Sweyn there linked up with a local nobleman, Hereward the Wake. The abbey of Peterborough was sacked and, in June, William once again had to reach deep into his royal purse to pay off the troublemakers and see them on their way back to Denmark. A loyal commander was put in charge of the area, Turold of Malmesbury, but William was obliged to land an army in person which eventually took control of Ely in the summer of 1071 CE and so ensured East Anglia remained loyal to the king.

Another campaign was directed at Scotland in the following year in order to prevent the constant raids into northern England from that kingdom, and another result was the exile of Edgar to Flanders. It had been a long hard campaign since 1066 CE to secure England and there would continue to be occasional baronial revolts and threats from abroad but these would not be based on old Anglo-Saxon loyalties. The Conqueror had finally secured his kingdom, and a new era of English history began.