Saint Thomas Aquinas (l. 1225-1274, also known as the "Ox of Sicily" and the "Angelic Doctor") was a Dominican friar, mystic, theologian, and philosopher, all at once. Although he lived a relatively short life, dying at age 49, Thomas occupied the 13th century with a colossal presence. Physically, Thomas was known to be a very large man. Mentally, his mind was shown to be grand and expansive through his writings and speeches. Thomas wrote and lectured prolifically, traveling across Western Europe by personal request of the Pope as well as to distinguished universities.

Yet as well-connected as Thomas was to rich and powerful people, he opted for the simple life of a begging friar at the age of 18. So, while he taught and researched at prestigious academic institutions, Thomas lived among the poor throughout his life. In his philosophical writings, Aristotle took center stage. Thomas ultimately sought to reconcile faith and reason during an age when others argued that this was impossible. Aristotle’s ancient Greek philosophy served Thomas in this endeavor. Still, the philosophical worldview produced by Thomas went beyond Aristotle, incorporating Jesus Christ and the Catholic perspective. By the time that Thomas died, in 1274, he had left philosophical and religious legacies through his writings and actions which persist to this day.

Early Life

Thomas Aquinas was born in the Sicilian castle of Roccasecca (present-day Lazio) in 1225. Even though Thomas made a name for himself throughout the academic and religious world, he was born into a family that already carried a noble history. The family of Aquino was distinguished by their military service. Thomas's father, Landulf, was a knight who loyally served the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Moreover, the Aquino family had plans for Thomas to maintain their high-stakes political connections by becoming an abbot, following in the footsteps of Thomas' uncle Sinibald.

Thomas's family was left astounded by his decision to join a mendicant order, and they tried desperately to make him change his mind. Not only did the Aquino family involve the Pope, but they arranged for Thomas to be kidnapped on a journey with his Dominican brothers. Then they locked Thomas up in the Castle of Monte San Giovanni Campano, hoping he would relent to their wishes. Throughout all of this, Thomas refused to become an abbot or to renounce his dedication to the Dominican order. Events escalated further when Thomas's brothers (who were also responsible for his kidnapping) arranged for a prostitute to tempt Thomas into sinning. Thomas firmly refused, chasing the prostitute out of his room.

Dominican and Franciscan friars were new groups to the medieval church, and their lifestyles were quite different than those of traditional monks. Friars lived lives of poverty, replacing traditional silk robes with the rougher and cheaper clothing of peasants. They also gave up high-class political life for day-to-day experiences among laborers and homeless people. So, the life that Thomas entered into as a teenager was radically different, and perhaps in some ways embarrassing, to the wealthy and powerful expectations of the Aquino family.

School Life

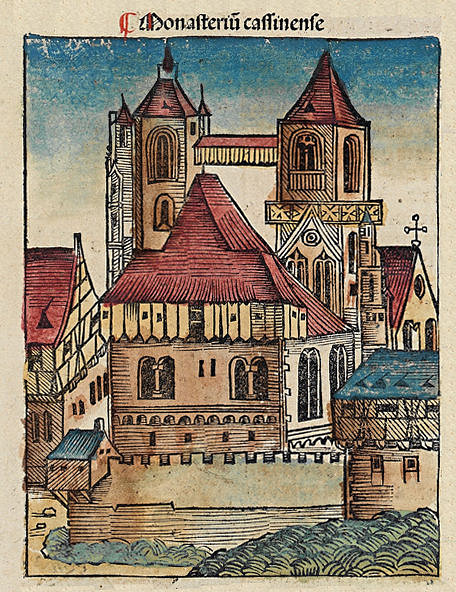

Thomas attended school at a young age and excelled in his academic work. From one account of his life, Thomas shocked his instructors when he suddenly and bluntly asked "What is God?" during a lesson at the monastery of Monte Cassino (Chesterton, 27). Clearly, Thomas’s deep thoughts began at a young age. However, this was not evident to many of his fellow students. It was also in school that Thomas earned the nickname of the "Dumb Ox." Students called him the "Dumb Ox" because Thomas was incredibly silent during class and of course tall and bulky. However, his peers turned out to err in their assessment of Thomas's intellectual abilities.

After Thomas's successful struggle to become a Dominican friar, he became the student of Albert the Great (also known as Albertus Magnus). Under Albert’s guidance, Thomas flourished. Thomas traveled with Albert to Cologne, Paris, and back to Italy as they studied, lectured, and wrote for academies and the Church. At one point, Albert reflected "we have called him the Dumb Ox, but he will bellow so loud that the sound of his voice will be heard throughout the whole world" (Hourly History, 18) Indeed, Thomas's philosophical and theological works would have a great impact upon the world during his life and into the future, as he dealt with the controversies and riddles of the Middle Ages.

Thomas first encountered the works of Aristotle in Naples. He was still in his teens during this time and had just left the abbey of Monte Cassino after Frederick II (l. 1194-1250) occupied the area with soldiers. Thomas's schooling in Naples was not under the control of the Catholic Church, and it was here that his liberal arts education was greatly expanded. Thomas studied the fields of astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, rhetoric, and music. The fact that Thomas studied both in the abbey of Monte Cassino and then Naples during his youth was important because between these places of learning he became immersed in the ideas of the Bible as well as the philosophical concepts of the liberal arts. This combination of religious and secular education would prove fateful as Thomas reached his scholarly prime.

Controversies of the Time

The controversies of Thomas's time revolved around power and knowledge. The Popes of the 13th century found their authority increasingly challenged by the power of the Holy Roman Empire, while the Catholic religious faith battled against new and challenging ideas about science and reason. Pope Gregory IX and Pope Innocent IV battled against Emperor Frederick II, and Thomas's family personally experienced this decades-long struggle. For example, Thomas's father directly served Frederick II while one of Thomas's brothers, Rinaldo, was martyred by Frederick for his loyalty to the Church. When Thomas committed himself to the Dominican Order, he made it clear that his loyalties were with the Pope and not the Holy Roman Emperor.

There were also academic and religious controversies that Thomas did not shy away from in his oral debates and writings. When Thomas was reaching his prime as a scholar, Aristotle was just being introduced to the Western world. Aristotle’s writings were preserved in Arabic from the East, and soon Latin translations of Aristotle were produced. The Catholic Church originally opposed Aristotle’s work, banning it from being taught by religious institutions. Moreover, there were groups of people within the Catholic Church who held Augustian philosophical views, relating much of their ideas to Plato. So not only was there a general conflict between religion and philosophy at the time but also between two philosophies, namely, Plato's and Aristotle’s. Ultimately, Thomas would bring Aristotle under the umbrella of Catholic thinking making the Greek thinker not only accepted within religious schools but celebrated and passionately studied.

Still, it was no easy task that Thomas set out for himself. Aristotle was not controversial without reason, in the Catholic Church. Some Medieval scholars argued that Aristotle’s philosophy went against the Christian religion. Overall, these scholars saw a conflict between faith and reason. While faith led a Christian to believe in God, reason led someone to question or deny God. For instance, Siger of Brabant (c. 1240-1284) followed the philosophy of Averroes (1126-1198), arguing that there are two conflicting perspectives. If someone followed their reasoning, they would come to see the world in a particular way that conflicted with the beliefs espoused by the Church. Thomas passionately opposed this view, arguing that faith and reason worked together to support the one truth of God.

Thomas outlined a hierarchy of knowledge, which all fell under the ultimate God-head. For instance, if someone decided to go out and study plants using scientific and secular methods, Thomas would have approved of this. On the other hand, Thomas would have disagreed that this scientific and secular way of studying things could reveal the totality of knowledge. So, all knowledge about plants only provided a small piece of the puzzle for Thomas, and while reason might teach someone many things, it could not teach someone all things. To pursue the highest study, which according to Thomas was theology, one had to move beyond the use of science and reason to consider faith and revelation as well.

Works

By the end of his life, Thomas had produced millions of words and thousands of articles. He debated extensively with others in universities, and he wrote works that directly dealt with the controversies of his time. His book, Summa Theologica, is still considered to be Thomas's highest academic achievement. It is not solely studied by Catholic scholars but also remains an enduring part of the classical curriculum, and both religious and non-religious academics study it closely to this day. The Summa is split into three parts, with the second part divided into two subsections. Its parts escalate from first considering the levels of life and governing to ultimately discussing the incarnation of Christ. Overall, the Summa aims to teach its readers how to be disciples of God, covering the philosophical and theological realms of reality.

Within his philosophical explorations, Thomas discusses ethics, physics, politics, and metaphysics. Beyond strictly philosophical work, Thomas wrote biblical commentaries, prayers, poetry, and more. Throughout much of his writing, Thomas is known for his logical and open-minded style. He would often begin with a question or heretical idea, giving the opposing view a fair hearing, before thoroughly dismantling it.

A famous example of this can be read in the Summa Theologica. Within these multiple volumes, Thomas asks at one point what the proper name of God should be. In reference to the biblical story of Moses and the burning bush, some would argue that the best name for God is "He Who Is" (in Latin: Qui Est; Summa Theologica I, Q. 13, Article 11.). Before Thomas defends the name Qui Est, he makes the case that this is in fact not the best name for God. Some say that God cannot be named, others that "good" is the best name for God. After Thomas explores these opposing views, he argues that Qui Est is the best name for God by not only referring to biblical authority but also appealing to philosophical reason. Because God’s essence is existence itself, he alone merits the predicate of being or existence. This synthesis of faith and reason is partly what makes Thomas's thinking so remarkable.

Mystical Experiences

Beyond being a philosopher, theologian, and friar, Thomas was also known as a mystic. As a mystic, he reportedly experienced visions and supernatural visitations. For example, after Thomas drove the prostitute out of his room, he was said to be visited by two angels who wrapped a cord of chastity around him. Although Thomas maintained a very quiet demeanor throughout his life, to his closest friends he would relate other mystical experiences like these.

Another story relates that Thomas was attending mass in December of 1273 when he saw something that fundamentally altered the course of his life. Whatever Thomas saw led him to say "everything I have written seems to me as straw in comparison with what I have seen" (Kerr, 19). Not only did Thomas keep to his word and refuse to write any further, but he then died a few months later, in 1274. Thomas was beginning a journey to Lyons at the command of Pope Gregory X when he fell ill and took refuge in a Fossanova monastery. In this monastery, Thomas gave his final confession and passed away.

Legacy

Thomas Aquinas was granted sainthood by the Catholic Church in 1323, and he was given the title of "Angelic Doctor" in 1567. Although Thomas's works would eventually gain a foundational presence in Roman Catholic colleges, his ideas were not immediately embraced by all Catholics. Right after Thomas's death, the theology department from Paris renounced a series of philosophical claims which included much of Thomas's thinking. A well-known opponent of Thomism was Canterbury’s Archbishop Robert Kilwardby (1215-1279), who considered some of Thomas's basic views about nature and divinity almost heretical. About a decade after Thomas died, the Franciscan Order banned the Summa Theologica from those who were untrained in considering his ideas.

However, despite these antagonisms, Thomas's philosophical and theological work was eventually accepted into the church and celebrated alongside scripture. Popes Innocent VI, Urban V, Pius V, Innocent XII, Clement XII, and Benedict XIV spoke well of Thomas and his works at various points in time. Centuries after Thomas's death, in 1879, Pope Leo XIII crafted the encyclical letter Aeterni Patris which endorsed Thomistic thought as "golden wisdom" (Aeterni Patris, section 31) Pope Leo XIII (served 1878-1903) was battling with Post-Enlightenment thinking, and Thomas's philosophy was his primary weapon in this struggle. Beyond the words and actions of popes, Thomas also inspired human rights theory, put forth in the 15th and 16th centuries by Spanish Dominicans, such as Francisco de Vitoria and Bartolomé de las Casas. These Catholic friars were disturbed by the cruel conditions of Spain’s American colonies, so they sought to use Thomistic thought as a justification for human rights for the protection of indigenous peoples.

With all of these different impacts considered, Thomas's thoughts remain relevant and debated today. Colleges continue to be founded in Thomas's name too, as people are continuously inspired by Thomas's academic spirit. Notably, during the 1970s the archbishop Fulton Sheen helped to found the Thomas Aquinas College. As it has turned out, Albert the Great’s claim that this "Ox" would "bellow" for the whole world to hear was prophetic indeed.