Themistocles (c. 524 - c. 460 BCE) was an Athenian statesman and general (strategos) whose emphasis on naval power and military skills were instrumental during the Persian wars, victory in which ensured that Greece survived its greatest ever threat. As the historian Thucydides stated in his History of the Peloponnesian War, 'Themistocles was a man who exhibited the most indubitable signs of genius; indeed, in this particular he has a claim on our admiration quite extraordinary and unparalleled.' (1.138.3). A brilliant strategist and canny politician he was perhaps a little too thirsty for glory and power for his own good but Themistocles was, without doubt, one of the most important and colourful figures of Classical Athens.

Early Life

Themistocles life is described by three notable ancient sources: Herodotus (c. 484 - c. 425 BCE), Thucydides (c. 460 - c. 399 BCE), and Plutarch (c. 45 CE - c. 120 CE). The first two are positive and praise the general's intelligence and quick wits while Plutarch presents a talented leader thirsty for power at any cost. Of his early life we know little except that, unusually for those who rose to the top echelons of power in Athens at the time, Themistocles did not come from an aristocratic family but a more humble middle-class one. In addition, we know that his mother was not an Athenian and his father was Neokles of the Lycomid family. According to Plutarch he was not a particularly gifted student and spent his free-time as a youth writing and performing speeches. His lack of qualifications is famously referenced in the following quote from the same writer,

Whenever in later life he found himself at any cultivated or elegant social gathering and was sneered at by men who regarded themselves as better educated, he could only defend himself rather arrogantly by saying that he had never learned how to tune a lyre or play a harp, but that he knew how to take a small or insignificant city in hand and raise it to glory and greatness. (Themistocles, 78)

Plutarch also tells us he had two daughters called Sybaris and Italia and one son, whom Themistocles once described as the most powerful man in Greece:

He once said jokingly that his son, who was spoiled by his mother and through her by himself, was more powerful than any man in Greece, 'for the Athenians command the Greeks, I command the Athenians, his mother commands me, and he commands her.' (Themistocles, 95)

Themistocles & Athenian Naval Power

Made archon in 493 BCE (although the significance of the title in this case is disputed by historians and may not refer to the typically understood highest administrative position) he is credited with developing Athens' port – the Piraeus – and building its fortifications and making it the largest naval base in the Greek world. As Thucydides puts it 'he [Themistocles] was always advising the Athenians, if a day should come when they were hard pressed by land, to go down into the Piraeus, and defy the world with their fleet' (The History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.93.3).

This was, then, the beginning of Athens becoming a significant and enduring naval power in the ancient Mediterranean. Still convinced that this was the way forward for the city, Themistocles, a decade later in 483 BCE, would use the excuse of an on-going conflict with Aegina to push for the surplus revenue from the silver mines of Laureion (discovered c. 503 BCE) to be used to build war ships expanding the Athenian fleet from 70 to 200 ships and so be ready too for a Persian invasion. In his focus on naval power Themistocles also claimed divine backing from the oracle of Apollo at sacred Delphi. He interpreted the typically obscure proclamation by the oracle that 'only a wooden wall will keep you safe' as meaning not fortification walls but wooden ships were Athens' best defence against invasion.

The Persian Wars

Persia invaded Greece in 490 BCE but the army of Darius was famously defeated at the battle of Marathon – a land battle of sword-wielding hoplites and archers. The beating of mighty Persia gave the Greeks magnificent confidence and the victory was celebrated as no other but, in the event, it was only a minor set-back to Persia's plans for invasion. For Darius' successor Xerxes would lead an even bigger army back on Greek soil in 480 BCE.

In the period between these two attacks Themistocles secured political control of Athens, even managing to exile his great rivals Xanthippus in 484 BCE and Aristides in 482 BCE. With Themistocles at the top of the political tree Athens sought to strengthen her navy and practically abandon the traditional hoplite soldier of Greek warfare. Heavily armoured and carrying sword and huge shield, the slow hoplite was relocated to fast-moving warships – the trireme with its triple bank of oars. Meeting an enemy at sea, ramming the opposition and finishing the job with a small team of hoplites would be Themistocles' strategy to see off Greece's greatest ever threat.

The Battle of Salamis

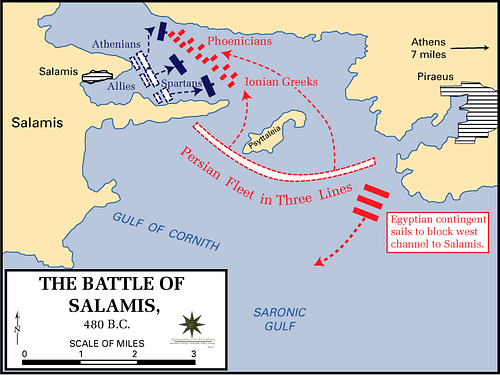

In August 480 BCE the Persian army was met at the mountain pass of Thermopylae by a small band of Greeks led by Spartan King Leonidas. They held the pass for three days, and at the same time the Greeks, with the Athenian contingent led by Themistocles, managed to hold off the Persians at the indecisive naval battle at Artemision. Such was Themistocles' faith in his naval supremacy he ordered the abandonment of Athens (if a 3rd century BCE inscription known as the 'Themistocles Decree' from Troezen is to be believed). The combined Greek fleet, meanwhile, re-grouped in September at Salamis in the Saronic Gulf, west of Piraeus. The fleet included ships from some 30 city-states, notably from Corinth and Aegina, and made up a total of some 300 ships. Themistocles commanded the Athenian contingent, by far the largest in the fleet with perhaps 200 ships. The Persian fleet, although greatly exaggerated by ancient writers, was probably larger with around 500 ships.

At this point some of the Greek states were in favour of abandoning Athens and a naval conflict; instead their proposal was to fortify the Isthmus of Corinth. Themistocles then may have sent word to the Persians of this possibility. He also had the Ionians and Carians in Xerxes' army spread messages to the effect that their loyalty was not to be trusted in the event of battle. These mixed messages and possible indicators of fractions in the Greek coalition galvanized the Persians into action so that they moved at night and blocked the straits, preventing the Greek fleet from abandoning their position. The wily Themistocles urged the wavering Greeks to action, retorting to one commander: 'those left behind at the starting line are never crowned with the victor's wreath' (Histories, 8.59). He would have his naval engagement and have it exactly where he wanted - Salamis.

When daylight came the battle commenced. The Greeks held back and drew the bigger Persian fleet into the narrow straits. In addition, Themistocles knew that at a certain time of day a breeze and heavy swell would come and the Persians would be unprepared for this. In the confusion, the Persians had no maneuverability, their space was further limited by more of their ships coming in from their rear, and their sailors had no shore to retreat to after their vessel was sunk, unlike the Greeks. Picking off the Persian ships one at a time and spurred on by the knowledge they were fighting for their lives and their way-of-life, the Greeks were victorious. Themistocles was treated as a hero and even given honours by Athens' great rival city Sparta.

Final Victory

Xerxes went back home to Susa but the Persian land army, now commanded by Mardonius, was still a significant threat and so the two sides clashed again, this time on land at Plataea in August 479 BCE. These forces were commanded by Xanthippus and Aristides, back from exile, and there is no mention of Themistocles. Once again though, the Greeks, fielding the largest hoplite army ever seen, won the battle which finally ended Persia's ambitions in Greece.

Themistocles Rebuilds Athens

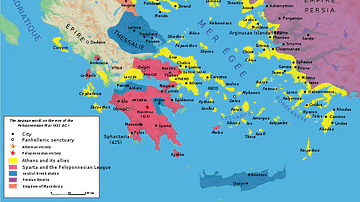

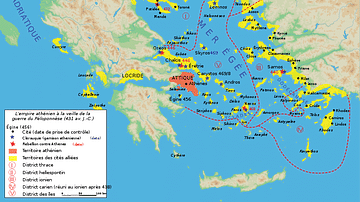

The Persian wars won a freedom which would allow Greece a never-before-seen period of artistic and cultural endeavour which would form the foundations of Western culture for millennia. More immediately, Themistocles re-fortified Athens and the Piraeus, and he also established the Kerameikos cemetery. To ensure Greece could resist any future attacks the Delian League was formed in 477 BCE. This was a federation of Greek city-states led by, and later to be entirely dominated by, Athens with each member contributing ships and money.

Exile & Death

Athens was never in such a strong position but the career of Themistocles was, unfortunately, heading for a nose-dive. He was, following accusations of bribery, sacrilege, and a suspicious association with Spartan traitor Pausanias exiled from the city from 476 to 471 BCE. Themistocles' shadow remained, at least in the arts, as it was in 472 BCE that the great playwright Aeschylus produced his Persians which described the aftermath of Themistocles' and Athens' great victory at Salamis.

Rather ironically, and after a brief stay in Argos and then Corcyra (Corfu), Themistocles fled from Greece by merchant vessel and was welcomed in Persia by Artaxerxes I. He was made governor of Magnesia in Ionia where coins were minted bearing his name. Understandably, the Athenians saw this as treason and officially declared Themistocles a traitor, condemned him to death, and confiscated all his property. It was not to be a happy move for Themistocles as he died in Magnesia not long afterwards, with rumours suggesting he may have been poisoned or that he even committed suicide. More probably dying of illness, Thucydides claimed his bones were secretly returned to Athens but the fact that his son continued his reign in Magnesia and a tomb was built for the great Athenian would suggest this is unlikely.

![Greek Trireme [Illustration]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/154.jpg?v=1626534003)