Clovis I (or Chlodovech, 466-511/513 CE), king of the Franks, is considered the founding father of the Merovingian Dynasty, which would continue for over 200 years. Clovis became king at the age of 15, and by the time of his death 30 years later, he had become the first king to rule over all the Frankish tribes, a firm ally of the Byzantine Empire, and a Christian king. Clovis' policies, and military brilliance, consolidated the regions of Gaul under his rule and, today, he is considered the founder of France.

Rise to Power

Towards the end of the 5th century CE, the Roman Empire in the west was dying. Aside from its economic decline, the empire was being bombarded on all sides by a series of attacks from the Huns, the Visigoths, and the Ostrogoths. In 410 CE Rome even succumbed to a three-day siege by the Gothic king Alaric. Finally, in 476 CE, with the overthrow of Emperor Romulus Augustulus, the Western Roman Empire fell. With the demise of Rome, many of the barbaric tribal kings carved out a portion of the old empire for themselves. One of these barbarians would conquer Gaul and establish a family dynasty that would last for over two centuries. His name was Chlodovech - known to history as Clovis I.

Clovis Assumes the Throne

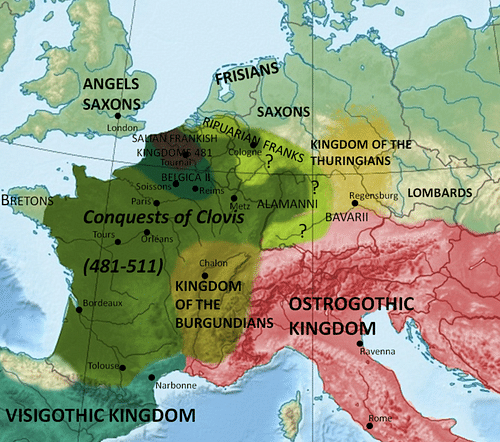

In 481 CE, Clovis, the founding father of the Merovingian Dynasty, assumed the throne at the tender age of 15 when his father Childeric, king of a Germanic tribe known as the Salian Franks, died. The pagan king who had fought alongside the Romans against the Huns was honored in death as he had been in life: buried along with weapons, gold, jewelry, and 15 horses. The family name "Merovingian" comes from Clovis' grandfather Merovech, who had also fought alongside the Romans, dying in 456 CE. The young Frankish king had been prepared well by his father and wasted little time in establishing himself as a major force in Europe when, at the age of 20, he opposed Syagrius, the last governor of Roman Gaul.

Conquest of Gaul

Along with a number of allies (including his cousins Ragnachar and Chararic), Clovis fought Syagrius at the Battle of Soissons in 486 CE and soundly defeated him. To avoid capture, Syagrius fled to Toulouse, a city located in southwestern Gaul, where he hoped to find refuge with the young Visigothic king Alaric II. Clovis and his army followed Syagrius and demanded his release. Alaric, wanting no part of a war with Clovis, surrendered him. Syagrius was returned to Soissons where he was reportedly beheaded. Although Clovis and Alaric had reached their agreement and parted ways, this would not be the last time that the two would meet, nor would the next time end so amicably. By the end of the year, Clovis had taken the cities of Rouen, Reims, and Paris and, by 491 CE, he had control of the entire west. He had also, by this time, ordered the assassination of the Frankish kings Chararic and Ragnachar, formerly his allies and possibly his relatives, and taken their kingdoms for himself.

Years later, English historian Edward Gibbon would write on Clovis' early conquest of Gaul:

When he first took the field, he had neither gold and silver in his coffers, nor wine and corn in his magazines; but he imitated the example of Caesar… and purchased soldiers with the fruits of conquest. After each successful battle or expedition the spoils were accumulated in one common mass; every warrior received his proportionable share, and the royal prerogative submitted to the equal regulations of military law. The untamed spirit of the barbarians was taught to acknowledge the advantages of regular discipline.

In 495 CE Clovis further increased his supremacy in Gaul when he drove the Alemani back across the upper Rhine River. According to some sources (primarily Gregory of Tours) his later victories over the Alemani (in 496 and 506 CE) influenced his decision to convert to Christianity.

Conversion to Christianity

Although raised a pagan (according to some historians, he would be the last of the pagan kings), Clovis realized that conversion to Christianity would be extremely beneficial to him if he ever hoped to secure the loyalty of all of the Frankish people. According to Gregory of Tours, his conversion came, in part, due to his marriage to the Burgundian princess Clotilde (daughter of Chilperic); her family was Arian, but she was not. According to the historian Roger Collins, however, Gregory should not be completely trusted in his account. Collins writes:

Unlike the reign of Theodoric, there is very little strictly contemporary evidence for that of Clovis" and further notes that the evidence which is available "makes it virtually certain that Clovis was a Christian by around the year 486 CE. (110)

Other historians, of course, disagree with Collins and claim that Gregory's account should be considered. Even if he is viewed by some as unreliable, Gregory of Tours is one of the few sources on the reign of Clovis and his conversion to Christianity. Gregory writes:

Clovis took to wife Clotilde, daughter of the Burgundians and a Christian. The queen unceasingly urged the king to acknowledge the true God, and forsake idols. But he could not in any wise be brought until war broke out with the Alamani … The two armies were in battle and there was great slaughter. Clovis' army was near to utter destruction. He… raised his eyes to heaven, saying … If thou shalt grant me victory over these enemies… I will believe in thee and be baptized in thy name.

According to Gregory, Clovis was victorious and acknowledged the Christian god through baptism. He previously resisted it strenuously, however, owing in large part to Clotilde's insistence on baptizing their children. Clovis refused to have his firstborn son baptized and so Clotilde had the child baptized secretly; afterwards, the boy fell ill and died. When their second son was born, he, too, was secretly baptized and, like his brother, also fell ill. This time, however, Clotilde prayed to God for his recovery, and according to Gregory of Tours, he became well. Soon after this event, Clovis was victorious against the Alemani in 496 and 506 CE and attributed his victories, and his son's life, to his god. Clovis was inspired by his newly found religious zeal to wage war against the Arian Visigoths which would be some of his most successful military campaigns. This crusade would ultimately push the Visigoths back into Spain and provide greater security for the realm of the Franks.

His conversion, administered by the bishop of Reims, would not only ensure the loyalty of the conquered provinces but also recognition by Anastasius, the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, who was as interested in the success of those who shared his brand of Christianity as he was in the downfall of those who did not.

Clovis & the Goths

After his conversion, and with the support of his people and the church, Clovis continued his war with the Visigoths (a struggle he faced throughout his reign), eventually meeting them at the Battle of Vouille in 507 CE at near Poitiers, a city in west-central Gaul, where he defeated and killed their king, Alaric II. The Ostrogothic king of Italy, Theodoric (who was Alaric's ally) was prevented from helping Alaric by the Byzantine emperor Anastasius because Theodoric owed his allegiance first to the empire who had encouraged his rise to power.

Theodoric, like Alaric, was an Arian Christian, while Anastasius was a Nicean (or Trinitarian) Christian, as Clovis was. Anastasius would not, under any circumstances, allow an Arian king to support another Arian ruler against a "true Christian" such as Clovis. Even if Anastasius had not intervened, however, it is unlikely Theodoric could have joined the battle against Clovis as he was married to Clovis's sister, Audofleda, in 492 CE; a marriage Theodoric himself had sought to bind his kingdom to that of Clovis' in alliance. Theodoric was in a difficult position, however, as he had sent one of his daughters in marriage to Alaric II. His choice in remaining out of the war was finally dictated by Anastasius but, as his later actions would prove, it was hardly the choice Theodoric would have made on his own.

After defeating the Visigoths, Clovis returned to Tours, where he was met by the emperor of the east who presented the victorious king with the purple tunic of a consul. With the Visigoths defeated and his realm secure, Clovis elected to rule his united empire from Paris. Attempts to further expand his domain were hampered by Theodoric's intervention. Clovis had wanted the whole of the Aquitanian provinces which had been under Alaric II's rule but, in 508 CE, Theodoric took control of Provence and, by 511 CE, had secured the former Visigothic lands for himself.

Death & Legacy

In November of 511 CE Clovis died (there is some disagreement over the exact year, and some historians cite 513 CE), leaving a kingdom that was a blend of both Roman and Germanic cultures: language, worship, and law. Clovis believed it important to preserve many of the old Roman traditions and, in fact, had modeled his early reign on that of Julius Caesar. Although he has been accused of slaughtering fellow Frankish kings (some even his relatives), it should be noted that this practice was hardly unusual for the time. By the time of his death, he had extended his authority from the north and west, southward to the Pyrenees. He had defeated the Alemanni, Burgundians, and Visigoths; however, his passing would end the expansion of the Franks.

Upon his death, his empire was, according to tradition, divided among his four sons; the “Do-Nothing Kings” who would do little, if anything, to expand their holdings or improve the lives of the people. Clovis' name would live on through his dynasty, the Merovingians, and he is considered the founder of the modern nation of France. History would ultimately Latinize his name to Louis; a name that would live on in French royalty for centuries through 18 kings and remains popular in French culture to the present day.