Brundisium (modern Brindisi), located on the Adriatic coast of southern Italy, was a Messapian and then Roman town of great strategic importance throughout antiquity. Although architectural remains are sparse, the city has several claims to fame. Brundisium is the end of the road for the Appian Way, was a traditional launching point for armies and travellers to the East, and played a pivotal role in both the Punic wars and Roman civil wars. Amongst its more impressive artefacts are many examples of Hellenistic and Roman bronze statuary which have been rescued from the town's harbour.

Early Settlement

The area of Brindisi was inhabited in Palaeolithic times some 12,000 years ago and the site of Torre Testa just 7 km to the north was the most important settlement in the region at that time. Thousands of stone tools and other artefacts have been discovered which belonged to the hunter-gatherers of the period. A continued presence in the Neolithic period and Bronze Age is attested by additional finds.

Messapian & Greek Town

Located at the very bottom of the Italian peninsula, in local mythology Brundisium was first settled by either Diomedes, a hero of the Trojan War, or Phalanthus, the Spartan who was also credited with founding nearby Tarentum (modern Taranto). Yet other sources suggest Brundisium was founded by settlers from Crete. Certainly, a Greek influence, if not actually full Greek colonization, is indicated in the cemetery at Tor Pisani. Little is known today regarding the town when it was inhabited by the Messapians, one of the tribes who lived in the 'heel' of Italy which constitutes modern Apulia. Their name for the town was Brentesion which may derive from the Messapian brentos, meaning 'deer's head', which describes the form of the harbour with its two distinctive promontories.

The best surviving examples of Messapian culture are ceramics. In particular, the high-handled amphorae known as trozella are unique to the region and have geometrical and plant motif decorative designs. There is evidence of a long and bitter rivalry with Tarentum (modern Taranto), the Spartan colony some 75 kilometres to the west on Italy's southern coast. Brundusium minted its own coinage and formed an alliance with Thurii c. 440 BCE, another Greek colony to the west built on the site of old Sybaris.

Roman Brundisium

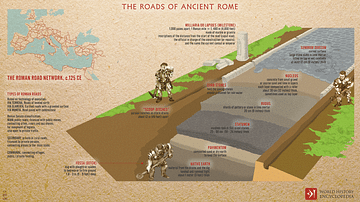

Brundisium started to take on a greater regional significance only from the 3rd century BCE onwards when Rome began to expand throughout the Italian peninsula. The Romans conquered the city in 266 BCE and a colony was formally established at Brundisium in 247 or 244 BCE. The city was then fortified in order to ensure the Romans kept hold of the excellent double harbour they had acquired. Around the same time, the great Roman road the Via Appia (Appian Way) was extended to reach the city, connecting it with Rome itself and bringing its total paved length to 569 km or 385 Roman miles. Brundisium consequently became the main point of departure for anyone travelling to Greece and the East and usurped Tarentum's position as the most important port in the south. Today a 19.2 m tall single marble column stands near the waterfront which was traditionally thought to mark the spot where the road finally ends. In fact, inscriptions reveal that the column once belonged to a building with a religious or commemorative function connected to the sea.

During the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca had attacked several Roman coastal cities in search of booty for his mercenaries and one of them was Brundisium in 247 BCE. These skirmishes, though, were largely a minor distraction from the main battlefront in Sicily. The city became more directly embroiled in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) when Hannibal invaded Italy and encamped in the southern corner of the peninsula. The Carthaginian general desperately needed a port through which he could receive reinforcements and supplies from Africa but the Romans successfully blockaded the harbours of the southern coast.

Sulla gave Brundisium an exemption from the portoria, the tax duty imposed on the import and export of goods at ports, and the town was given municipium status around 89 BCE, which granted its citizens Roman citizenship. However, the city's fortunes would soon suffer a dramatic downturn during the violent final stages of the Roman Republic. In the civil war of the 1st century BCE, Brundisium would, once again, find itself centre stage in the theatre of a bloody and brutal war. Julius Caesar captured the city in 49 BCE so that he could prevent his great rival Pompey from fleeing Italy. Then it was attacked again in 40 BCE, this time by Mark Antony. The city's handy location at the foot of Italy was proving something of a liability for the local residents. Brundisium was also the site of the accord, known as the Treaty of Brundisium, between Antony and Octavian to carve up the Roman Empire between themselves. When Octavian won the war and became the first Roman Emperor as Augustus, a triumphal arch was set up in the city in his honour.

Yet another historical event linked to the city is the death of Virgil there in 19 BCE, shortly after the writer returned from a trip to Greece. The city would continue to exist as a minor Roman town in the imperial period with the slave trade, fishing and shipbuilding providing plenty of employment and wealth for some as evidenced in the large villas of the period. A Christian community was founded by Saint Leucius of Alexandria in the second half of the 2nd century CE.

Unfortunately, the continual inhabitation of the site and constant reuse of ancient building materials has obscured its development in later times and left few standing remains. Excavations have revealed traces of all the usual features one would expect to find in a Roman town: a Roman forum, market square, Roman baths, aqueducts, amphitheatre, necropolis, and regular town plan. There was also an armamentarium or arsenal and several warehouses, both indicative of Brundisium's primary function as a gateway to Roman Italy for goods and troops.

Artefacts

While little remains of the ancient buildings of Brundisium, the city, and especially its harbour, has provided some outstanding examples of Greek and Roman art for posterity. Amongst these survivors are many bronze statues. Unfortunately, most are incomplete but some of them remain sufficiently intact to still instil awe at the skills of ancient metalworkers. A notable piece is the head and torso of a figure known as the Hellenistic Prince which dates to the 2nd or 1st century BCE. Another fine head has been identified as a Greek philosopher, possibly Antisthenes, and dates to the 4th century BCE. Besides many examples of trozella already mentioned, the town's archaeological museum possesses a fine collection of Greek pottery and terracotta figurines including a charming depiction of a crouched Aphrodite emerging from her shell.