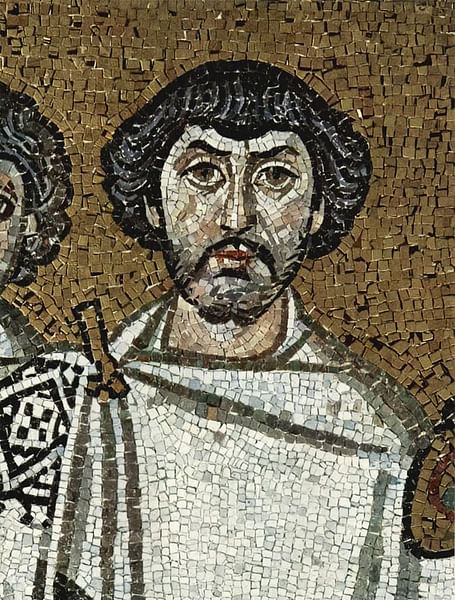

Flavius Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) was born in Illyria (the western part of the Balkan Peninsula) to poor parents and rose to become one of the greatest generals, if not the greatest, of the Byzantine Empire. Belisarius is listed among the notable candidates for the title of 'Last of the Romans' by which is meant the last individual who most perfectly embodies the values of the Roman Empire at its best. He served as commander of the military under the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) with whom he had a notoriously difficult relationship.

He first enlisted in the army under the Byzantine emperor Justin I (r. 518-527 CE) and, upon Justin's death, his successor, Justinian I, awarded Belisarius full command of the army. He put down the Nika uprising in Constantinople in 532 CE, the result of resentment against Justinian I, slaughtering between 20-30,000 people. He then commanded Byzantine forces against the Persians, Vandals, Goths, and Bulgars, serving the empire nobly and faithfully until his death.

Early Career & the Nika Revolt

Belisarius' native tongue was Thracian with Latin as his second language. As a teenage recruit in the Byzantine army, he proved himself an able soldier and obviously made an impression on his superiors because he was elevated in rank during the reign of Justin I and soon after commanded the emperor's personal bodyguard. Justin I was so impressed by the young man that he made him an officer and then promoted him to command.

Whatever promise Justin I saw in Belisarius, it was not proven by his first engagements. Belisarius was defeated a number of times before he seems to have gotten a better grasp of full-scale engagements and the command of large forces. When Justin I died, in spite of Belisarius' defeats, Justinian I promoted him to command of the eastern forces against the Sassanid Empire, and he won a great victory at the Battle of Dara in 530 CE during the Iberian War. His next engagement, however, the Battle of Callinicum in 531 CE, was not so successful as he was defeated with heavy losses. Belisarius was ordered back to Constantinople to stand charges for his defeat on the grounds of incompetence but was cleared of all charges and resumed his duties.

Justinian I's policies – especially concerning taxation and the methods of tax collection – were extremely unpopular with the people of his capital city of Constantinople and, in 532 CE, this situation exploded in the so-called Nika Riots. The immediate cause of the conflict was the arrest and imprisonment of two athletes from the two rival chariot-racing sports teams the Blues and the Greens. A number of athletes had been arrested for murder after a fight following a race and most had been executed. Justinian I commuted the sentences of the last two from execution to imprisonment when it became clear how unhappy the populace was with his previous choices.

The crowds at the Hippodrome in January 532 CE were no happier with the imprisonment verdict than they had been with execution and, during the races that day, they broke out in a riot chanting “Nika!” (“win”) and stormed Justinian I's palace. The crowd was supported by senators who were also tired of Justinian I's policies and his tendency to ignore them in favor of his prefect John the Cappadocian (served c. 532-541 CE), a corrupt official who was in charge of taxes.

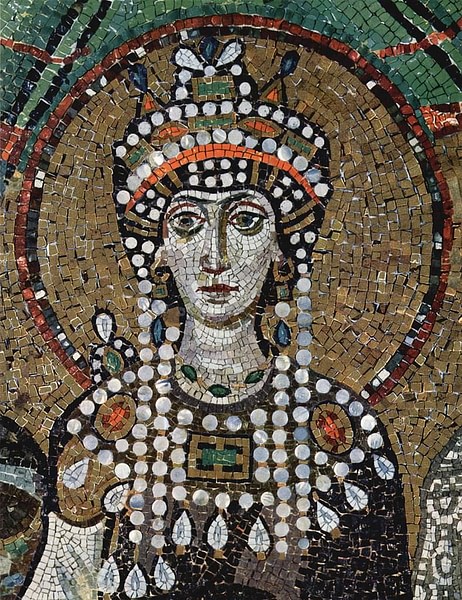

The mob chose the consul Hypatius as their new emperor, and he encouraged their revolt further, speaking to the crowds now packing the Hippodrome. Justinian I privately gave up without a fight and was going to flee the city with his supporters but was stopped by his wife Theodora (l. 500-548 CE) who strongly advised against this by pointing out that he might save his life by deserting the city but would afterwards find it a life not worth living as there would be no honor or dignity in it.

Justinian I took her counsel and ordered Belisarius to deal with the riot. Belisarius, after gaining entrance to the Hippodrome, crushed the rebellion, killing between 20,000 and 30,000 citizens (modern-day scholars set the number considerably higher). Hypatius was captured and later executed.

North Africa Campaign

The rebellion crushed, Justinian I then sent Belisarius against the Vandals in 533 CE to win back African provinces to the empire and 'liberate' Trinitarian (Nicene) Christians from the perceived tyranny of the Vandals who practiced Arian Christianity. The Vandals had conquered the African provinces of the former Roman Empire under the leadership of their king Gaiseric (r. 428-478 CE). The Arian Christian Vandals, after establishing themselves, systematically persecuted the Nicene Christians who were considered followers of the 'Roman' brand of Christianity.

Whether Justinian I actually ordered the invasion of North Africa to stop these persecutions is still debated as is the question of whether he ordered the invasion at all since some scholars, citing the work of Procopius, point out that the invasion was actually Belisarius' idea. It seems Justinian I's only initial goal was to win back the lucrative ports of Tripolitania which included Oea, Sabratha, and Leptis Magna on the coast. Since these ports and adjacent lands were no longer governed by the empire, they were not generating any income for Justinian I, whose popularity was at an all-time low following the Nika Riots and other setbacks and who needed a great victory (and more money) to restore his prestige.

In 533 CE, Belisarius embarked with 5,000 cavalry, 10,000 infantry, 20,000 sailors on a fleet of 500 warships, and 92 smaller warships rowed by 2,000 slaves. This huge invading force left Constantinople and landed in Sicily to resupply. According to historian J. F. C. Fuller, it was only at this point that a full-scale invasion of North Africa was decided upon by Belisarius once he received intelligence that the Vandal king Gelimer (r. 530-534 CE) had no idea he was coming.

Belisarius landed his forces in North Africa and marched toward Carthage, the capital of the Vandal kingdom. Along the way, he maintained strict discipline among his troops so that none of the populations they passed through were harmed or wronged. His chivalrous conduct toward the people of North Africa won their trust and they provided him with supplies and intelligence. Gelimer, having finally learned that a Byzantine force was descending on his capital, launched a plan whereby he would trap his enemy in the valley of Ad Decium and, in a three-pronged surprise attack, destroy the Byzantines.

Gelimer's plan relied on a precisely coordinated attack led by himself, his brother Ammatus, and his nephew Gibamund. In order for the plan to work, everyone had to move at exactly the right time. As Fuller notes, “because correct timing was the prerequisite of success, in a clockless age it would have been a fluke had the three columns engaged simultaneously” (312). Ammatus struck first before Gelimer and Gibamund were in position and was quickly killed while his forces scattered. Gibamund then charged without waiting for Gelimer and was defeated by the Byzantine cavalry. By the time Gelimer arrived, he found only the bodies of his defeated army and his dead brother. He was so distraught over Ammatus' death that he halted the army in order to bury him with the proper rites. This allowed Belisarius to reach Carthage and take it easily.

Gelimer marched on Carthage but was defeated at the Battle of Tricameron in December 533 CE. Gelimer fled the field in the face of the Byzantine onslaught, and his troops then fell into a panic and broke ranks. Gelimer was later hunted down, captured, and brought back in chains to Constantinople as part of Belisarius' triumph.

Gothic Wars

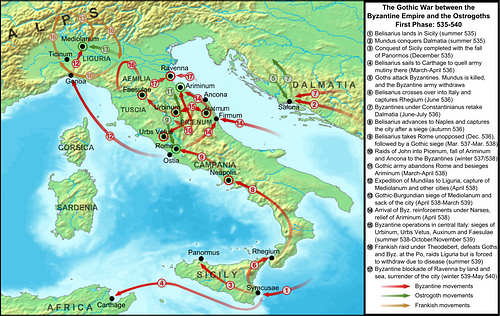

In 535 CE Belisarius was sent against the Ostrogoths in Italy. The country had been stable and prosperous under the Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great (r. 493-526 CE) who provided the Byzantine Empire with revenue but, since his death, had fallen into chaos under the rule of self-seeking and weak monarchs. At the time Justinian I decided to take action, Theodoric's daughter Amalasuntha (l. c. 495-535 CE), the reigning queen, had been assassinated by her cousin Theodahad who then assumed the throne.

Belisarius took Sicily first in 535 CE and then Naples and Rome in 536 CE. Theodahad was not up to the task of defending his cities and, further, had proven himself a very poor king in every respect. He was assassinated by Amalasuntha's son-in-law Witigis (also given as Vitiges, r. 536-540 CE) in 536 CE who then organized defense of his realm but did no better than Theodahad. In 540 CE, Belisarius took the city of Ravenna and secured Witigis as prisoner. Justinian I then offered the Goths his terms which, in Belisarius' view, were too generous: they could keep an independent kingdom and, in spite of the trouble they had caused, would only have to surrender half of their treasury to Justinian I. Justinian I seems to have had no intention of honoring this deal and, even if he had, Belisarius considered it needlessly lenient.

The Goths trusted neither Justinian nor his terms but did trust Belisarius who had behaved honorably toward the conquered throughout the war. They answered that they would agree to the terms of surrender if Belisarius endorsed the treaty. Belisarius could not do so, however, as an honorable man and soldier. A faction of the Ostrogoth nobility suggested a way around this impasse by making Belisarius himself their new king.

Belisarius pretended to accept their proposal but, loyal to Justinian I and knowing himself an abler soldier than statesman, went along with all their preparations to crown him at Ravenna and then had the ringleaders of the plot arrested and claimed all of the Ostrogoth Empire, and all of the treasury, in Justinian I's name. Scholar David L. Bongard comments:

A brave and skillful soldier, Belisarius was a talented tactician, bold, wily, and flexible; despite his shabby treatment at the hands of Justinian, he always behaved loyally [even to the point of refusing] the offer of a crown of his own at Ravenna. (Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, 76)

Return to Constantinople & Persian Wars

Even though Belisarius had never given Justinian I any cause, the emperor grew suspicious of his loyalty. Belisarius was incredibly popular among his men as well as among those he conquered and so, in Justinian I's mind, there was no reason why his general would not rise up against him. He thought it best to keep Belisarius close at hand where he could be better controlled and so recalled Belisarius to Constantinople and replaced him in Italy with Byzantine officials. This proved a grave error as the officials were corrupt and the people of Italy, especially the Ostrogoths, suffered under their administration.

Back in Constantinople, Belisarius was as popular as ever – far more than Justinian I. Historian Will Durant cites Procopius in reporting how the people of the city regarded the general:

The Byzantines took delight in watching Belisarius as he came forth from his home each day… For his progress resembled a crowded festival procession, since he was always escorted by a large number of Vandals, Goths, and Moors. Furthermore, he had a fine figure, and was tall and remarkably handsome. But his conduct was so meek, and his manners so affable, that he seemed like a very poor man, and one of no repute. (110)

Belisarius lived a relatively quiet life at this time with his wife Antonia (l. c. 495 - c. 565 CE), to whom he was devoted even though she was unfaithful to him. Antonia had followed Belisarius on his campaigns and seemed to be a loyal wife and confidante but, according to Procopius, she was actually in the service of the empress Theodora to spy on Belisarius.

He was not home for long, however, before Justinian I sent him to fight the Persians. Belisarius won these wars through his usual careful tactics and the use of deceit. At one point, when he knew he was outnumbered and the Persian general was trying to gain intelligence on the strength of his forces, Belisarius arrived at a meeting with Persian ambassadors with a large contingent of men (6,000 according to Procopius) dressed as if they were a hunting expedition. The impression was that, if a mere hunting party numbered so many, Belisarius' army must vastly outnumber the Persians. Instead of attacking, the Persians retreated and Belisarius was victorious.

Totila's War

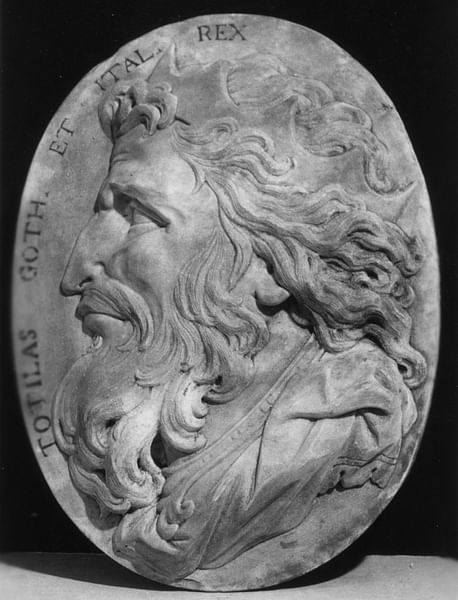

While he was off fighting the Persians, the situation in Italy had worsened. The Byzantine officials, whom Justinian had given governorship to, had so misused their powers that a Gothic uprising, led by a charismatic, nationalist Ostrogoth named Totila (birth name Baduila-Badua, r. 541-552 CE), had thrown the region into chaos. Totila was chosen as the Ostrogoth king and proceeded to drive out the Byzantines and claim Italy as his own kingdom.

Totila was a charismatic and effective general while the Byzantine commanders sent against him by Justinian I were more concerned with how they could profit personally from the campaign. Totila defeated them easily and, by 542 CE, had over 20,000 men under his command with his ranks swelling daily. When he defeated a Byzantine army, he offered clemency and many who were taken prisoner switched sides and fought for him.

In 545 CE, Justinian I sent Belisarius back to Italy to deal with Totila and, in December of that year, Totila took the city of Rome. Even though Rome was no longer the seat of power it had been, it still retained symbolic importance for the Byzantines. Totila sent word to Constantinople that he was open to negotiations but Justinian I wrote back that he should deal with Belisarius. Totila, frustrated, wrote Belisarius that, if the Byzantines did not withdraw from Italy and leave him in peace, he would destroy Rome and execute the senators who were his prisoners.

Belisarius responded in a carefully worded letter in which he explained that Totila's demands were impossible because Italy belonged to the Byzantine Empire and Justinian I was not about to surrender it lightly. Belisarius highlighted Totila's reputation as an honorable and merciful general who spared cities and those he had defeated and warned that, if he went ahead with his plan to destroy Rome and execute his prisoners, his good name would forever be tarnished. Rome was a famous city, Belisarius noted, and if Totila left it intact, he would be remembered well; if he destroyed it, he would forever be held in disdain.

Totila agreed in a move which scholar Herwig Wolfram (expressing scholarly consensus) refers to as “the momentous mistake of giving up Rome” (356). He needed all the men under his command to continue the war and so could not leave Rome fortified; he therefore chose to abandon it. Belisarius took the city afterwards, repaired and strengthened the walls, and garrisoned it, in an effort to deny Totila a significant resource in any future negotiations.

Totila continued his successful campaigns, outsmarting even Belisarius, while his army grew – largely with recruits from defeated imperial forces – between 547-548 CE until, in 550 CE, he returned and took Rome back. He then sent emissaries to Constantinople to negotiate a peace but his messengers were denied an audience and then arrested. Justinian recalled Belisarius from Italy and replaced him with the general Germanus, second husband of the late Amalasuntha, but Germanus died before he could reach Italy and was replaced by Narses (l. c. 480-573 CE) who would defeat Totila at the Battle of Taginae in 552 CE, killing him and restoring Italy to the Byzantine Empire.

Conclusion

Back in Constantinople, and despite his poor treatment at Justinian I's hands, Belisarius again accepted the command of troops and crushed the Bulgars when they attempted to invade the Byzantine Empire in 559 CE. He once again ably drove the enemy back across the border and secured the boundaries of the empire. Even after all his service to Justinian I, Belisarius was accused of corruption (generally understood today as trumped-up charges) and imprisoned in 562 CE.

Justinian I pardoned him, however, and restored him to his previous standing and honour at the Byzantine court. A myth later grew up around this event in which Justinian I had Belisarius blinded and the great general became a beggar on the streets of Constantinople. This myth, however, has no basis in fact even though many works of art, such as Jacque-Louis David's painting Belisarius, have depicted it as historical truth. Belisarius died of natural causes in 565 CE, within only a few weeks of Justinian I, at his estate just outside Constantinople. Will Durant expresses the majority opinion of Belisarius' reputation, writing:

No general since Caesar ever won so many victories with such limited resources of men and funds; few ever surpassed him in strategy or tactics, in popularity with his men and mercy to his foes; perhaps it merits note that the greatest generals – Alexander, Caesar, Belisarius, Saladin, Napoleon – found clemency a mighty engine of war. (108)

He is remembered as one of the greatest military commanders in history and, as Durant notes, is regularly compared with the most celebrated generals of all time. Unlike many of them, however, Belisarius valued humility, regularly consulting with his staff before making decisions which would affect them, and consistently adhered to his own code of honor, maintaining his integrity under circumstances which would have corrupted a lesser man.