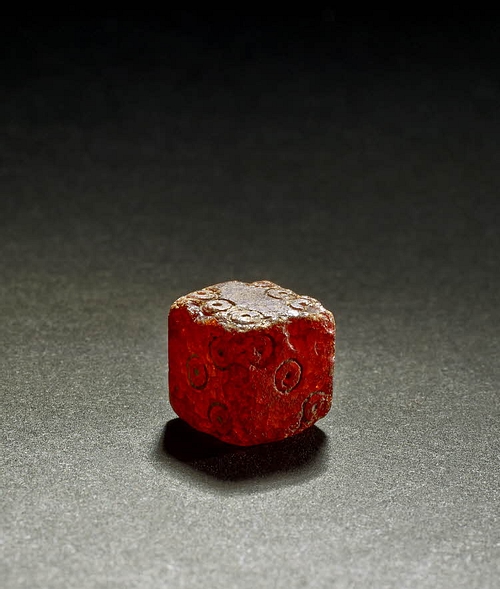

Amber, the fossilised resin of trees, was used throughout the ancient world for jewellery and decorative objects. The main source was the Baltic region where amber, known to mineralogists as succinite, was washed up onto beaches and easily collected. Besides its aesthetic qualities and ease of carving and polishing, amber, for many ancient peoples, had mysterious qualities such as protecting the wearer, warding off evil, and curing diseases.

Origins & Myths

Although found in northern Europe and Sicily, the amber used by the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean came mostly from the Baltic area. As the fossilised resin of trees, rough pieces of amber naturally washed up on beaches where they were collected and then cut, carved, and polished into pieces of fine jewellery and ornaments. There were various myths to explain where this wondrous material came from, notably one retold by Ovid. The Roman writer describes the old belief that amber was nothing less than the crystallised tears of Clymene and her daughters who had been transformed in their grief to poplar trees following the tragic death of Phaethon. Clymene's dashing young son had foolishly lost control of the sun-chariot of his father, the sun god Helios, when he had tried to ride it across the sky. In order to prevent the earth from being scorched by the falling sun, Zeus had felt compelled to strike Phaethon down with one of his thunderbolts. Hence the Greeks called amber 'electrum' after their name for the sun, elector.

Other ancient writers claimed that amber was the solidified rays of the sun somehow captured as they struck the earth. Other theories were that it came from a remote temple in Ethiopia, a river in India, was the tears of birds mourning the fallen hero Meleager, or even came from the urine of the lynx - the male producing a brighter version than the female. Colourful though the stories and explanations might be, the ancients themselves may have taken them with a healthy pinch of salt, just as we do now, for writers such as Aristotle had long since identified amber as a "hardened resin" and many amber myths involve trees so, in any case, they were not far from the truth.

A little later, in the 1st century CE, the Roman writer Pliny the Elder attempted to classify and describe all precious stones and materials in his Natural History. In Book 37, chapters 11-12, he describes amber in some detail. He notes that it is a relatively common substance which is frequently traded. He struggles to come up with a reason as to exactly why it is popular: "luxury has not been able, as yet, to devise any justification for the use of it." He is dismissive of the Phatheon myth as repeated by Greek authors from Aeschylus to Euripides and of many other tall tales. He then proceeds to debunk all the claims where, geographically speaking, amber came from, although he does in the process mention Phytheas, who noted that it washed up on the shores of Germany. Pliny generally agrees with Phytheas, noting that the tribes of Germania called amber glaesum and that it comes originally from pine trees, which, he states, is obvious if amber is burnt as it smells of pine. He also knew it was originally in a liquid state because of the trapped insects sometimes seen inside larger pieces. He did not grasp the concept of fossilisation but rather explained the hardening of the resin as a process somehow performed by the sea.

Tacitus, the 1st-2nd-century CE Roman historian, gives the following description of amber and its collection by tribes on German shores:

They even explore the sea; and are the only people who gather amber, which by them is called Glese, and is collected among the shallows and upon the shore. With the usual indifference of barbarians, they have not inquired or ascertained from what natural object or by what means it is produced. It long lay disregarded amidst other things thrown up by the sea, till our luxury gave it a name. Useless to them, they gather it in the rough; bring it unwrought; and wonder at the price they receive. It would appear, however, to be an exudation from certain trees; since reptiles, and even winged animals, are often seen shining through it, which, entangled in it while in a liquid state, became enclosed as it hardened. I should therefore imagine that, as the luxuriant woods and groves in the secret recesses of the East exude frankincense and balsam, so there are the same in the islands and continents of the West; which, acted upon by the near rays of the sun, drop their liquid juices into the subjacent sea, whence, by the force of tempests, they are thrown out upon the opposite coasts. If the nature of amber be examined by the application of fire, it kindles like a torch, with a thick and odorous flame; and presently resolves into a glutinous matter resembling pitch or resin. (Germania, 45)

Properties

Amber is relatively soft and so was an ideal material to be cut and carved into beads and other forms of jewellery. Saws, files, and drills were used to create the desired shape and engraved designs. Ancient jewellers from the Bronze Age onwards were already highly skilled in carving much harder semi-precious materials such as carnelian and garnet, so amber posed no particular challenge to their abilities. Amber also has the advantage that it can be polished using abrasives to produce an appealing gleam. One significant disadvantage of the material is that it is susceptible to degradation. Fading over time following exposure to air, amber also becomes more opaque and so many pieces of ancient amber work do not, today, look quite as impressive as they did when they were first made.

Already mysterious because nobody was quite sure where it actually came from, many ancient peoples regarded amber as a somewhat mystical material capable of protecting the wearer in some way. The use of amulets for just such a purpose was especially common in ancient Egypt and Greece, so to make the object (which could be almost anything from miniature representations of gods to body parts) doubly powerful, amber was a good choice. Not only a prevention against misfortune, amber, it was thought, also had healing powers. Roman cemeteries, for example, and especially those in the north-western provinces, often have child burials containing amber beads which were likely placed there to function as amulets.

Pliny notes in his Natural History that some people believed amber could help with problems specifically connected to the tonsils, mouth, and throat, as well as mental disorders and bladder problems. Amber was even ground and mixed with rose oil and honey to treat eye and ear infections. Considering that amber is, after all, a natural substance and that it contains succinic acid, which was used in medicines prior to the use of antibiotics, perhaps the ancient belief in its medicinal qualities is not quite so fanciful.

Finally, the ancients noticed that amber, when rubbed (and so producing a negative charge), is capable of attraction. The ability to attract light objects such as dried grasses or wheat chaff led to the Persians calling amber kahruba or 'straw-robber'. This was yet another quality which added to the mystery and allure of amber.

Historical Use

The earliest amber workshops in the Baltic date to the Neolithic period. Trade contacts between Bronze Age and also later cultures ensured that amber travelled around Europe, thanks mainly to the Germanic and central European tribes who wanted to exchange it for metals they could use themselves or to trade on to tribes in Britain and Scandinavia. Seafaring traders such as the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Carthaginians helped spread amber even further afield. Amber moved down from the Baltic via rivers from west Jutland across Germany and down the Po Valley of northern Italy to the Adriatic sea. From there it was carried by sea traders to the Levant and Near East. Amber beads have also been found in ancient northern and central France, and the Iberian peninsula.

Artefacts made from the material have been discovered at Bronze age sites such as Ugarit, Atchana, Minoan Crete (more rarely), and Mycenaean cities (especially Thebes). Tests on the amber found in Mycenaean shaft graves indicate that it largely came from the Baltic, and similar tests have shown that many amber pieces found in the Near East came from Mycenaean workshops. Amber beads found on the Bronze Age Uluburun shipwreck further attest to the trade of amber in this period.

Perhaps because of its rarity so far from its source, amber was particularly prized in the Near East where it was largely reserved for and even became a symbol of royal power and status. Priests were another group who wore amber as a mark of distinction. Tests have revealed that amber found at sites across the Levant and Near East came from the Baltic. Amber is a rarer find in ancient Egypt but amber beaded jewellery and rings have been found in several tombs there.

During the Iron Age the east coast of Italy became something of a specialist in amber, with Picenum, in particular, thriving on the production of amber goods. Villanovan Verucchio (a pre-Etruscan site) was another manufacturing centre from the 9th century BCE with tombs of females, especially, containing significant quantities of amber made into disks for earrings, necklaces, spindles, sewn-on decorations for clothing, and curious leech-shaped fibulae composed of individually carved pieces joined with bronze. In this period there are also finds in these places of a 'false' amber which came from the fossilised resin of trees in the Levant.

Amber goods are a common feature of Archaic Greek art but the material seems to have gone out of fashion by the Classical period. Central Italy continued its production of amber with the Etruscans producing jewellery and small figurines of animals and humans in the material.

The Romans ensured amber made a comeback across the Mediterranean. They also had a lasting influence on the material's name as the Latin name ambrum led to the Arab word anbar which, in turn, led to the modern English term amber. Prized and fashionable again, amber was imported, as before, via the rivers of Germania. Tribes in Germania Libera were no longer merely trading on the raw material either but had set up their own workshops so that they could trade the finished articles with Rome. Aquileia in central Italy, in particular, became a noted centre of production between the 1st and 3rd century CE. Amber was used to make jewellery, figurines, handles, and even small containers and goblets. That certain amber pieces could fetch high prices is attested by Pliny the Elder in the following extract from his Natural History:

So highly valued is this as an object of luxury, that a very diminutive human effigy, made of amber, has been known to sell at a higher price than living men even, in stout and vigorous health. (Book 37:12.2)

Largely worn by Roman women, amber even gave its name to a tint of hair colour. Its protective qualities were not forgotten, either, as gladiators often made sure to have pieces attached to their fighting nets. The use of amber in the Roman world declined from the 3rd century CE but it was still widely used in the Baltic regions, a fact indicated by the 6th-century CE writer Cassiodorus who quotes a thank-you letter for Baltic amber sent to Emperor Theodoric. In the Medieval period, the Armenians became the new champions of amber and ensured its trade and manufacture into fine decorative pieces continued into modern times.