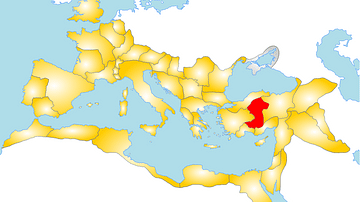

Tarsus was a city in ancient Cilicia located in the modern-day province of Mersin, Turkey. It is one of the oldest continually inhabited urban centers in the world, dating back to the Neolithic Period. It was built close by the Cydnus River (modern-day Berdan River) and was an important trade center for most of its history. It is best known as the birthplace of Saint Paul (also known as Saul of Tarsus l. c. 5- c. 64 CE) and, according to Plutarch, Cleopatra VII (l. c. 69-30 BCE) met Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE) aboard her ship outside the city's port-side gate, the ruins of which are a popular tourist attraction in the present day. Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) recuperated in Tarsus when he fell ill there after swimming in the Cydnus in 333 BCE after taking the city in his conquest of Cilicia.

Tarsus flourished under the Hittites c. 1700-1200 BCE, was sacked in the 12th or 13th century BCE (almost certainly by the Sea Peoples), and resumed its former status as a vital trade center under the Assyrians (between c. 700-612 BCE), the Persians (between c. 547-333 BCE), next under Alexander the Great (between c. 333-323 BCE), and afterwards divided between two of his generals who founded the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires, until the region was taken by Rome in 103 BCE.

After 64 BCE, it was the capital of the district of Cilicia Campestris and remained the capital when the area was redistricted and renamed Cilicia Prima and later passed to the control of the Byzantine Empire. It was taken with the rest of Cilicia by Muslim invasions c. 700 CE, returned to Byzantine control c. 965 CE, and continued as an important city for commerce after it was taken by the Ottoman Empire after 1453 CE.

Early History

Later Roman texts claim that the city was founded by the grandson of a woman named Anchiale who established a nearby town named after her and whose son, Cydnus, gave his name to the river. Cydnus' son, Parthenius, founded the city of Parthenia, which was afterwards known as Tarsus. This story is late Byzantine fiction, however, as the city first appears in Assyrian texts as having been known as Tarsisi by the Akkadians (between c. 2334-2083 BCE) and was called Tarsa by the Hittites in honor of one of their gods. It was already a significant trade center under the Hittites and was most likely developed from a much earlier urban center by the Hatti around 2500 BCE.

The Hittites called the region Kizzuwatna and made Tarsa their capital. Trade flourished under the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344-1322 BCE) and his successors who made the city wealthy. Between c. 1276-1178 BCE, a coalition of invaders and pirates known as the Sea Peoples ravaged the Mediterranean region and are almost certainly responsible for the destruction of Tarsus. Hittite records toward the end of their empire are now lost but the Egyptians recorded a number of cities in Anatolia as having been destroyed by the Sea Peoples, among them Troy, Miletus, and Tarsus.

As the Seleucid Empire weakened in c. 110 BCE, their control over Cilicia grew lax, encouraging the growth of piracy in the region. Rome first intervened in 103 BCE, conquering the area which would later be known as Cilicia Campestris, in an effort to root out the Cilician pirates who were harassing their ships and disrupting trade and this begins Rome's involvement with the region.

Tarsus & the Roman Republic

Rome was involved in the Mithridatic Wars to the north between 89-63 BCE. Mithridates VI (l. 120-63 BCE), as part of his strategy against Rome, had entered into agreements with the Cilician pirates to harass and plunder Roman trade vessels and ports. The piracy problem worsened for Rome as Mithridates VI encouraged it further and so the general Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) moved to take care of it permanently.

Unlike earlier efforts which had struck at the pirates on land, Pompey took the fight to the seas, partitioning the Mediterranean into 13 districts and assigning a fleet to capture the pirates in each starting in 67 BCE. In 89 days, he broke the Cilician pirates' power, capturing or destroying their ships, and by 66 BCE they were defeated. In 64 BCE, Pompey divided Cilicia into six districts and relocated a significant number of pirates to the district of Cilicia Campestris, including the city of Tarsus.

The former pirates were as industrious as farmers and laborers as they had been as thieves and kidnappers and the region flourished largely through their efforts. Roman administrators governed the region, and Rome now had a stable territory from which to launch campaigns into the Near East. The port at Tarsus, which had always been among the most lucrative, became even busier under Roman administration, and the city grew in wealth and opulence. Cilicia was left on its own during the civil war between Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) and Pompey, but both generals were in or near the region between 49-45 BCE.

Caesar was so impressed by Tarsus that he made it tax-exempt and lavished further favors on the city; in gratitude, Tarsus renamed itself Juliopolis. Caesar also rewarded the Jews of the region (and, by extension, all Jews who would eventually live under Roman rule) freedom to practice their religion in thanks for their support during his struggles with Pompey. His decree, most likely from 47 BCE, was upheld by Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE-14 CE) and the emperors who succeeded him.

After Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE, Mark Antony and Octavian (the future Augustus) pursued the conspirators and their forces, finally defeating them at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE. Antony was still in the region, at Tarsus, in 41 BCE when Queen Cleopatra of Egypt made her now-famous overture to him from her barge on the Cydnus outside the gates of Tarsus. Caesar and Cleopatra had been involved both politically and romantically and she now needed Antony's support and protection. On his side, Antony recognized the value of having a controlling interest in Egypt, Rome's breadbasket owing to their export of grain, and Tarsus was the beginning of their famous love affair and political alliance.

Tarsus & the Roman Empire

Antony's involvement with Cleopatra, as well as his overall comportment, at first irritated and later enraged Octavian, finally contributing to civil war between the generals which culminated in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE at which Antony and Cleopatra were defeated. They killed themselves shortly afterwards, and in 27 BCE, Octavian became Augustus Caesar, the first emperor of Rome. That same year, he redistricted Cilicia, joining it to Syria as the province of Syria-Cilicia Phoenice and ordering the construction of temples, administrative buildings, and roads.

A Roman road, possibly one of those Augustus decreed, can still be seen in modern-day Tarsus, though only a small part of it has been excavated. The roads of Cilicia linked it with the rest of the empire so that trade and travel became easier. The network of roads ran from Troy to Pergamum and from the Armenian Plateau down through the Cilician Gates, throughout Galatia, and on to Tarsus. Trade by land was now almost as easy as by water, but this did nothing to diminish the profits of Tarsus' port on the Cydnus.

Tarsus was the jewel of Cilicia at this time and trade brought people from all over the region, many of whom stayed. The former pirates Pompey had relocated were worshippers of Mithras, practicing the Persian religion of Mithraism which they introduced to the soldiers of Rome in and around Tarsus. Scholar A. N. Wilson comments:

Like any great port, Tarsus had a mixed population. The ancient writers speak of Tarseans as pirates, seafarers, and worshippers of Mithras… [the cult] became especially popular in the army, most of whom, in the first century, were Asiatics. Archaeologists show that Tarsus was a center of keen Mithraic worship until the downfall of the Empire. The most distinctive feature of Mithraic worship is that initiates either drank the blood of the sacred bull or drank a chalice of wine as a symbolic representation of blood. (25)

Mithraism was one of many “mystery cults” of the 1st century CE, so called not only because they claimed to know the mysteries of life and death but because their adherents kept the beliefs and rituals a secret, known only to initiates. Mithraism would grow from Cilicia, and specifically Tarsus, to become the most popular religion of the Roman Empire, eventually vying only with the Cult of Isis which came from Egypt and, finally, a minor mystery cult whose adherents were known as Galileans or Nazarenes but would eventually be called Christians and whose earliest champion was born in Tarsus.

Saint Paul

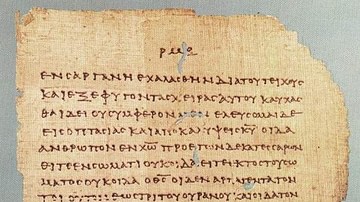

Saul, the future Saint Paul, was born in Tarsus a Roman Citizen and a devout Jew (Acts 22:28, Philippians 3:4-5). Everything known about him comes from the biblical book of Acts, the epistles which make up most of the Christian New Testament, and other narratives (such as The Acts of Paul and Thecla) not included in the Bible. His birth name was no doubt Saul while Paul (Paulus) was his Roman name which he naturally would have used more in his missionary work among the Gentiles. Contrary to popular opinion, there is no biblical evidence that Saul changed his name to Paul after his conversion experience. Acts 13:9 states that Saul was also called Paul and he is referred to as Saul elsewhere following his conversion.

He was sent to study in Jerusalem and became a prominent member of the Jewish community there (Acts 22:3). When the disciples of Jesus Christ began sharing their new faith, Saul was among their persecutors until he experienced a vision on his way to Damascus in which Jesus spoke to him and he was struck blind (Acts 9:3-9). After recovering his sight with the help of Christians, he became the great evangelist, traveling the Roman roads of Syria-Cilicia Phoenice to spread the new faith.

Many scholars and theologians over the years have noted that Saul's birthplace and upbringing influenced his vision of Christianity. He would have been aware of the Mithraic cult and their rituals as well as other religions such as the Cult of Hercules, Zoroastrianism, the Cult of Cybele, Manichaeism, the Cult of Isis, and many more. The popular Cult of Hercules was associated closely with the figure of the Dying and Reviving God – a deity who dies and returns to life – one of the earliest sorts of fertility-vegetative deities. In Tarsus, the cult (originally dedicated to the vegetation deity Sandan) was associated with three such figures: the Syrian Adonis, Babylonian Tammuz, and Egyptian Osiris (Wilson, 26). Hercules was “born” each year in the spring and “died” in the fall, both events marked by a religious festival. Wilson comments:

Every autumn in Tarsus the boy Paul would have seen the great funeral pyre at which the god was ritually burnt. The central mystery of the ritual was that the withering heat of the summer sun had brought the god to his death but that he would rise to life again in the spring, at about the time when the Jews were celebrating the Passover. From inscriptions in Tarsus we know that Herakles, in his dying and descent into Hades, was regarded as a divine savior. (26)

This early influence, according to some scholars (Hyam Maccoby among them), explains the difference between the Christianity of Peter and Paul's vision of the faith hinted at in Acts 15:1-35 and Galatians 2:11-21 (known as the Incident at Antioch). Two different versions of Christian belief and practice are suggested in these passages and Paul's seems to have won out. Through his letters and sermons on his many travels (from Cilicia to Greece to Rome to Palestine and back) Paul spread his vision of the dying and reviving Jesus Christ, and whether his message had anything to do with the actual ministry of Jesus of Nazareth is far from clear. There are a number of discrepancies between the message of Jesus of the gospels and the message in Paul's epistles and even between the figure of Paul in the Book of Acts and Paul as he presents himself in his letters.

Paul continued his extremely successful missionary efforts for approximately 30 years before he was martyred, according to Christian tradition, in Rome. The churches he founded, however, flourished and, after Constantine the Great legitimized Christianity in the 4th century CE, Christianity grew to become the dominant religion not only in Cilicia but throughout the ancient world.

Late Imperial Tarsus

Tarsus continued to flourish as well and was famous for both its wealth and the indolence of its citizens. The Greek Sophist Philostratus (l. c. 170-250 CE), writing on the life of the mystic and philosopher Apollonius of Tyana (l. c. 15-100 CE, himself the object of another 1st-century CE mystery cult), noted:

Apollonius found the atmosphere of the city harsh and strange and little conducive to the philosophic life for nowhere are men more addicted to luxury than here. Jesters and full of insolence are they all and they attend more to their fine linen than the Athenians did to wisdom. A stream called the Cydnus runs through their city, along the banks of which they sit like so many water-fowl. (Life of Apollonius of Tyna, I.7)

Philostratus' observation here is in keeping with the general view of Tarsus during the Roman Empire as a luxurious port city of great wealth and opulence. It was not only a trade center but the Roman administration center for the region and no expense was spared in creating temples, parks, and public baths. The emperor Commodus (l. 161-192 CE) was especially fond of the pleasures of Tarsus and the emperor Julian (l. 331-363 CE) admired it so much he planned on moving his capital there from Antioch but died before he could do so. Beautifully crafted terracotta figures have been found in Tarsus at the site of the Gozlukule mound and excavations there from 2007 CE on have revealed more. The popularity of the cults of Aphrodite and Dionysius is attested by a number of figures of them and is further testimony to two of the prime interests of the citizens.

Byzantine Tarsus

Tarsus continued this reputation even after the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, and the city became part of the Eastern Roman Empire, known as the Byzantine Empire, by which time its district was called Cilicia Prima. The emperors still held the city in special regard, and trade was as profitable as ever. Tarsus exported cereals, beans, grain, fish, olives, wine, tents (especially large tents for the Roman army) and a rough cloth known as cilicium. This cloth, made of goat hair, is referenced throughout the Middle Ages (c. 476-1500 CE) as cilice and was a popular form of penance. Penitents would wear the cilice shirt openly or under their clothes to suffer the discomfort of the coarse material which also apparently made one itch. Cilicium was originally created as material for tents, not clothing.

In the 7th century CE, the Byzantine Empire defended the region from adherents of the new religion of Islam whose warriors were seizing lands and converting people through various means but, most often, by the sword. The Muslims took Cilicia in 700 CE and, after setting up bases and turning churches into mosques, used Tarsus and other cities as staging areas for raids into other Byzantine regions.

This situation continued until the 10th century CE when the Byzantines were strong enough to retaliate in force under their emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (r. 963-969 CE). Nikephoros drove the Muslim invaders from Cilicia and re-established Byzantine control in 965 CE. The Byzantines would continue to control Tarsus and the surrounding region until the empire fell in 1453 CE and, after that, it became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Conclusion

Nothing exists of ancient Tarsus in the modern Turkish city except the partially excavated Roman road and part of the port gate (known as Cleopatra's Gate) which has been restored so extensively that little of the original seems to remain. Silt and other factors combined to move the Cydnus further away from the city even though it is still known as a lucrative trade center. Two tourist attractions, St. Paul's Church and St. Paul's Well have nothing to do with Saint Paul and were built centuries after his missionary work. The old city of Tarsus lies buried under the new and excavation is impossible without disrupting the lives and commercial interests of the citizens.

Certain areas in and around the city have yielded tantalizing pieces of work which suggest the opulence of ancient Tarsus. The ongoing excavations at Gozlukule mound, conducted since 2007 CE by Bogazici University, Istanbul, have brought to light numerous terracotta figures, as mentioned above, as well as evidence of the workshops which produced them. Tarsus remains a very pretty city, however, even if it does not approximate the jewel of Cilicia it was in the time of Imperial Rome, and has much to offer a visitor by way of attractive architecture, especially of the mosques, and the famous hospitality of the people.