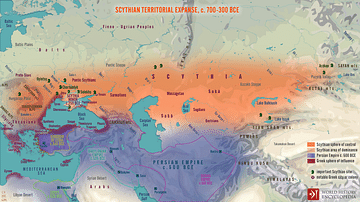

Scythian Art is best known for its 'animal art.' Flourishing between the 7th and 3rd centuries BCE on the steppe of Central Asia, with echoes of Celtic influence, the Scythians were known for their works in gold. Moreover, with the recent unearthing of their kurgans, a high level of cultural sophistication is reflected in their art and dress.

Décor

Reflecting their nomadic lifestyle, most Scythian décor was manufactured in plaque or appliqué style. With their flat profiles consisting of solid gold, gilded wood, leather cutouts, and felt appliqué, such items could be attached or sewn to the tack of their horses or perhaps hung on the walls of their house wagons. Dating from the late 6th to early 3rd century BCE, prolific examples of felt, leather, and wood horse decorations were found at the Bashadar and Pazyryk burial mounds in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia. From one saddle hung four detachable leather cutouts of twisting fish with gold-dot touches, each 58 cm (22 inches) long. Some felt saddle covers were highly decorated in a quilt-like fashion of contrasting colored squares or triangles, one was also decorated with leather rosettes with spots of gold in the middle, and others were decorated with leather eagles. One saddle was unusually decorated with felt appliqué of a multi-colored griffin, and another was covered with felt medallions, each 20 cm (8 in) wide having a spiral of six stylized eagle heads. The Scythians attached small segments of gilded wooden plaques of fantastic eagles and ram heads onto the bridles of their horses, and they also fastened gilded plaques of eagles and palmettes to the chest straps.

Solid gold ornaments were popular, too. While many of the gold pieces unearthed from the Scythian tombs were for personal wear, and the thousands of tiny gold panthers and boars covering the principles entombed suggest talisman-like attributes, the construction of other gold pieces reveals their purpose as décor. Some vessels adorning their environs are beautiful in their horizontal fluting, while others show remarkably detailed scenes in distinct relief of hunting scenes and Scythian warfare. Other thin plates display prey/predator scenes. Although some plaque-style pieces are small enough to have been worn, the size, shape, and weight of others reveal that they were likely hung.

The Scythians had exquisitely patterned felt wall hangings and carpets, like tapestries insulating the walls of medieval castles. It is likely the Scythians would have, for practical reasons, similarly insulated the walls of their house-wagons with their felt hangings and could have further decorated them with their gold plaques. Small plaques, varying from 2.5-5 cm (1-2 in) with evenly spaced holes at their perimeter, may have been sewn onto garments; others ranging from 15-40 cm (6-16 in) in length would have been hung to larger surfaces.

Headdresses

The Scythians were recognized for and took pride in their unique headdresses. From a functional basis – protecting the head from heat evaporation – the Scythians literally brought their headgear to new heights of fashion. Herodotus describes their "tall caps" as "erect, stiff, and tapering to a point" (7.64). His observation is confirmed in the Apadana relief at Persepolis of a Scythian armed delegation donning tall pointy headgear. On occasion, the Scythians brought their tall headgear to an even greater level of exaggeration. The well-known 'Golden Man' from the Issyk burial site near Lake Issyk donned a red pointed hat 65 cm (25 in) high. Crested with four miniature vertical spears, the base was adorned with fabulous golden animals, snow leopards, ibexes, winged tigers, and birds.

Further north, a headdress from the Pazyryk-2 kurgan, belonging to a chief, held a 34 cm (14 in) tall, elaborately carved mythic eagle holding the head of a deer in its beak. The 40-cm-tall (16 in) ladies' headdress at Mound 5 would have attracted similar attention. Found at other Altai sites, such headdresses of Scythian women (worn over a shaved head, with the ladies' topknot pulled through the top) were typically crested with deer silhouettes, then decorated with figures of birds, frame-rods, and hairpins of gold-leafed deer. Such exaggerated adornment would have brought conspicuous attention to the wearer.

As the Scythians beautified their environs and horses with gold décor and donned elaborate headdresses, their horses wore the same. At Pazyryk, one horse wore stylized stag antlers made of thick leather and tassels of red hair. Another horse's headdress, 50 cm (20 in) tall, consists of a cap topped with a ram's head with a bird in flight sitting between its horns, while yet another has a tall eagle head with a horn protruding from the top of its beak.

Personal Appearance

Like their everyday caps used in a practical way, many images of Scythian dress show the practical use of long-sleeved tunics, trousers, and boots. As their trousers are tucked into boots and cinched tight around the ankles to keep out the cold, the length of their jackets approaches the knees and are tied with a belt. The well-known plaque from the Black Sea Kul'Oba mound depicting back-to-back archers reveals tunics with rope-style trimming and trousers embellished with random stars. The golden beaker from the same site show trousers with evenly-spaced moons between lines. Nonetheless, besides their usual dress, the Scythians could, for the occasion, dress to the nines.

While their décor and decorations for their headdresses were mainly gold, gold for personal adornment was also popular. For example, gold bracelets, necklaces, and torcs are not uncommon. In the Altai Mountains, at the Arzhan-2 site at Tuva, gold earrings with granulated pendants were found. At Pazyryk-2, a pair of gold earrings with dangling cloisonné-like sections was unearthed. Adding to their variety of tastes, necklaces of colored stone and glass beads were also found. Besides their imaginative taste in gold, "the frozen tombs of the Altai provide an incomparable vision of the sheer exuberance of nomad dress: the love of bright, contrasting colors and intricate decorations formed by stitching, embroidery, and the attachment of leather cut-outs." Dress items include intricately embellished shoes, sleeves, and a lady's cape with a fur border. Moreover, as part of the Scythian dress, felt stockings were popular for both sexes. Found at Pazyrk-2, "stockings for the women were ornamented with the appliqué of lotus palmettes joined in a garland; men's stockings had heart-shaped figures." (Cunliffe, 207, 127)

Likewise, the sophistication of their garments was equally matched by an affinity for tattoos. As important as their fashionable dress, tattoos of abstract images of curled cats, stags, rams, antelope, goats, and mythic creatures held broad appeal for both sexes. While the body of a male principal at Pazyrk had legs, chest, back, and shoulder-to-hand tattoos of animals in the Scythian fashion, a female principal, popularly known as the Siberian Princess, also had tattoos of similar design and coverage. Just as tattoos today are meant to be shown and appreciated, Scythian tattoos also reflect a level of mutual appreciation.

Music & Dance

While the Black Sea and Altai Mountain discoveries reveal a refined taste in decoration, they also show Scythia's love of music and dance. Some items show erotic dancers (expertly captured in mid-action) swaying to the music. At the Sachnovka kurgan in central Ukraine, a golden headband shows a man playing the lyre. Pan pipes, made from bird bones, were also found at Kurgan 5 at Skatovka in the lower Volga region. In several tombs at Pazyryk, ox-horn drums were unearthed. Fabricated by stitching together two plates of horn and then sewing the skin membrane on to cover the head, such an instrument, when struck, would have made a unique resonating sound. At kurgan 2, a harp-like instrument was discovered that had at least four strings. A skilled musician's tones issued forth from this instrument must have been remarkable. According to Barry Cunliffe:

[It was] made from a single hollowed-out wooden resonator, the middle part of the body was covered by a wooden sounding board, while sounding membranes were stretched over the open part of the body. ... In more mellow moments, the Scythians enjoyed music. Music would no doubt have accompanied rituals and ceremonies, but it is tempting to imagine the tired horseman settling down with his kin to enjoy an evening of singing and dancing. (226-27)

Celtic Influences

The Scythians' Caucasian features described by 1st-century CE Chinese chroniclers and their Indo-European language support earlier Bronze Age origins in the West, likely from the Celts. Celtic influences indeed appear echoed in Scythian art, such as in torcs. Often made of multiple strands of gold wire twisted into thick neck rings, torcs were close-fitting and open-ended in the front, their terminals fabricated into mythical creatures or plain or stylized knobs. However, concerning other artistic expressions, as the Celts developed their graceful curvilinear patterns early on and as their intertwining designs became complex themes, the Scythians developed their own cultural identity and form of art. Still, influences are unmistakable.

While curves are usually added flourishes in Scythian art, the repeating curves on the gilt silver amphora from the Chertomlyk burial mound, near Nikopol, Ukraine, are remarkably Celtic-like, as are the cockerel appliqués on a coffin from Pazyryk-1, or the stylized horse ornament from Pazyryk-3 with its repeating curves of two elk heads facing out. All three date to around the 4th century BCE. As 'openwork' is defined by its regular patterns of openings and holes, some of the flat metalwork of the Celts, dating to around the 5th century BCE, is very similar to Scythian openwork of the same period.

Two belt plaques, for example, are remarkably similar. While both have coral inlay, the Celtic one, made of bronze (from the Rhineland in Germany, dating to the 5th century BCE) is of a stylized bull's head flanked by two griffin-like creatures. The Scythian gold plaque (from Southern Siberia, dating to the 3rd century BCE) is of a horse archer chasing and shooting a boar.

Themes & Styles

With echoes of Celtic curvilinear features, a unique, innovative departure for the Scythians was their depiction of scenes in mid-action. Apart from ingenious graceful curvilinear designs, Celtic life visuals are rather staid and unimaginative. However, like the Siberian openwork of the horse-archer with his bow fully drawn chasing down and shooting a boar from horseback, many Scythian pieces depict life in mid-action, often in dramatic ways. Besides the level of intricate craftsmanship in glittering gold, many Scythian artifacts tell a life story. So, a comb (like the famous Solokha comb dating to the 5th to early 4th century BCE) is not just a comb, but it is designed to show warriors in fierce combat.

Similarly, the pectoral from the Tolstaya Mogila kurgan shows scenes from daily life with exquisite, segmented detail in the upper register: the milking of a ewe, two men sewing a shirt, calf, and colts nursing. In contrast, the lower register displays dramatic prey/predator scenes of cats taking down a stag and griffins biting and clawing at horses. Then in choice places toward the neck are miniature goats, rabbits, dogs, grasshoppers, and birds. These two Black Sea artifacts found near the Dnieper River in southern Ukraine are typical of Scythian art in offering unique, sometimes dramatic snapshots of Scythian fashion, interests, beliefs, habits, and daily life-visuals like few burial goods do. Moreover, while some artifacts show serene life scenes, others depict humans hunting or in combat, like the Solokha comb, the archers from the Kul' Oba mound, or a plaque from the same site showing a horseman hunting a rabbit.

Another Scythian theme is their portrayal of animals. While the Celts crafted them in mythical, stylized, or unskilled natural forms, the Scythians brought their depictions to such a level of artistry and quantity, some describe them as Scythia's 'animal art.' The Scythians depicted animals in two ways: in abstract or lifelike form, either in a benign state or in conflict. Many items have prey/predator themes. From the Bratoliubivskyi kurgan, in the Khersonska region, a gold plate shows, in more natural form, a snow leopard attacking a stag. Then on several openwork plaques are abstract scenes of a cat biting and taking down a horse, a giant eagle mauling a yak, a tiger in combat with a monster, and the like. Such a common penchant for singular depictions of violent predation may have reflected the violence prevalent in Scythians' own lives as warriors.

Besides the images of animals attached to the tack of their horses or pinned to their headdresses (like the noblewomen's headdress at Ak-Alakha that was covered with feline figures of gold) on the finials of their ubiquitous priestly pole-tops are also figures of deer and birds. Additionally, some of the most common of their animal art are abstract depictions of recumbent deer and panthers.

Not only did the Scythians dress and surround themselves with animals, as mentioned, but they also tattooed their bodies with them. While such display might be considered solely a fashion statement or a form of artistic expression, considering the admixture of religious creed to the ancients' daily life, one wonders what part such images played in the belief system of Scythian religion. Since they surrounded themselves with them in such prolific ways, it appears they figured their destiny was intertwined, and as such, their animal images provided real fortune and protection. At the Arzhan-2 site (dating to the 7th century BCE), of the 9,300 objects found, 5,600 were gold, mostly tiny animal appliqués. Amazingly, 5000 of the gold appliqués were gold panthers worn equally by the 'king' and 'queen.'

Conclusion

As their abodes were house wagons, their ride horses, and their lifestyle nomadic, one might assume that the dress and artistry of the Scythians roaming the steppe of Central Asia would have been, at best, rudimentary. Yet, as their burial sites reveal, they surrounded and adorned themselves with art surprisingly varietal in their manufacture and sophisticated expression. As the Scythians decorated their horses with fantastic eagles and rams, and the interior of their house wagons with beautiful wall hangings and perhaps gold plaques, they brought the practicality of their headgear and clothing to new heights of style and adornment.

Retaining Celtic curvilinear aspects to their artistic designs, they also created their own style and themes. With a plethora of works in gold, often of intricate fashion, their artistry was of daily life scenes and animal depiction. As they surrounded, even tattooed, themselves with their animal images, their style swung between the remarkable realistic capturing of subject matter in mid-action and the abstract rendering of reality. Accordingly, though they were nomadic and militarily inclined, the Scythians were, at the same time, art connoisseurs of the first magnitude.